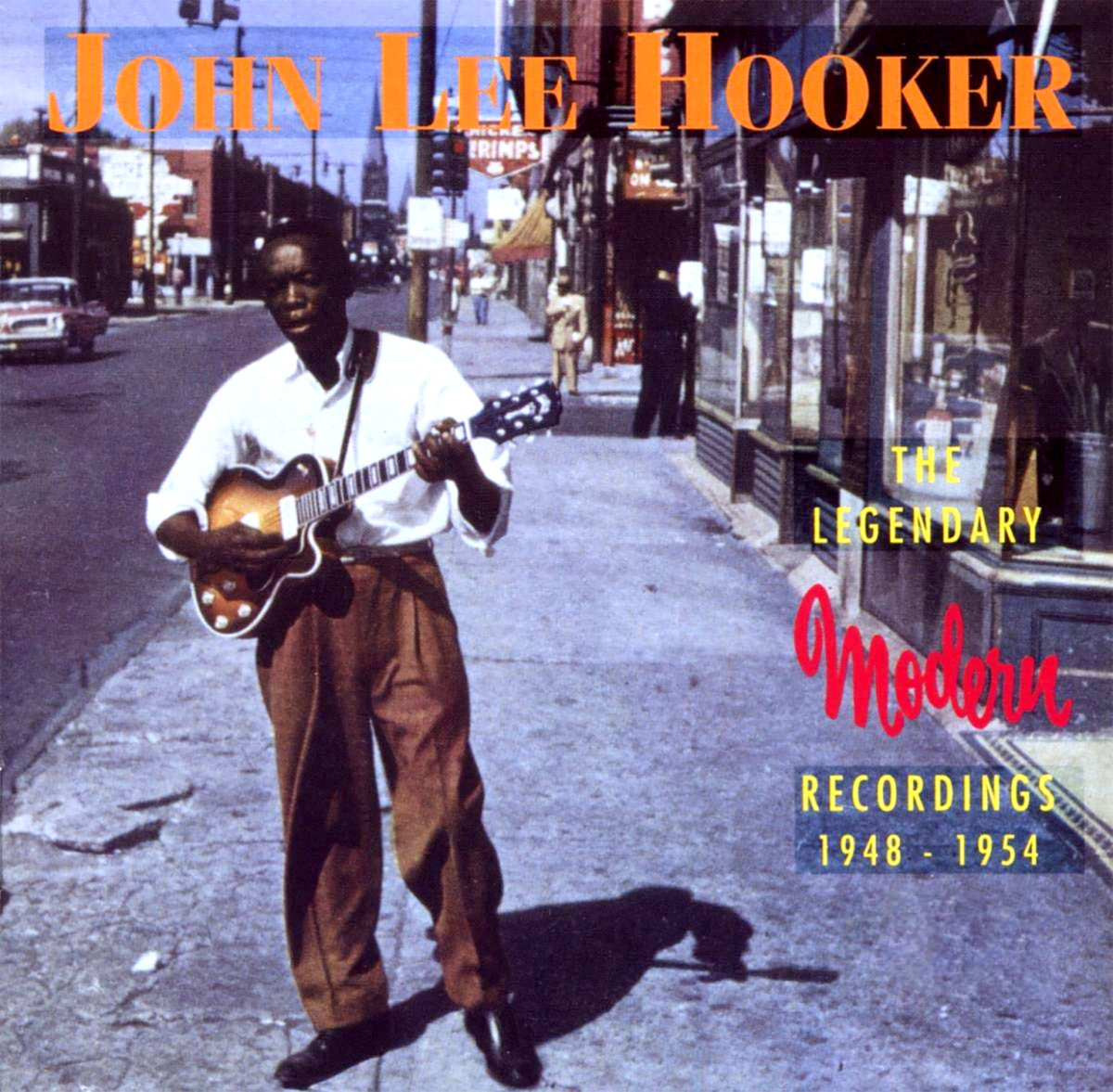

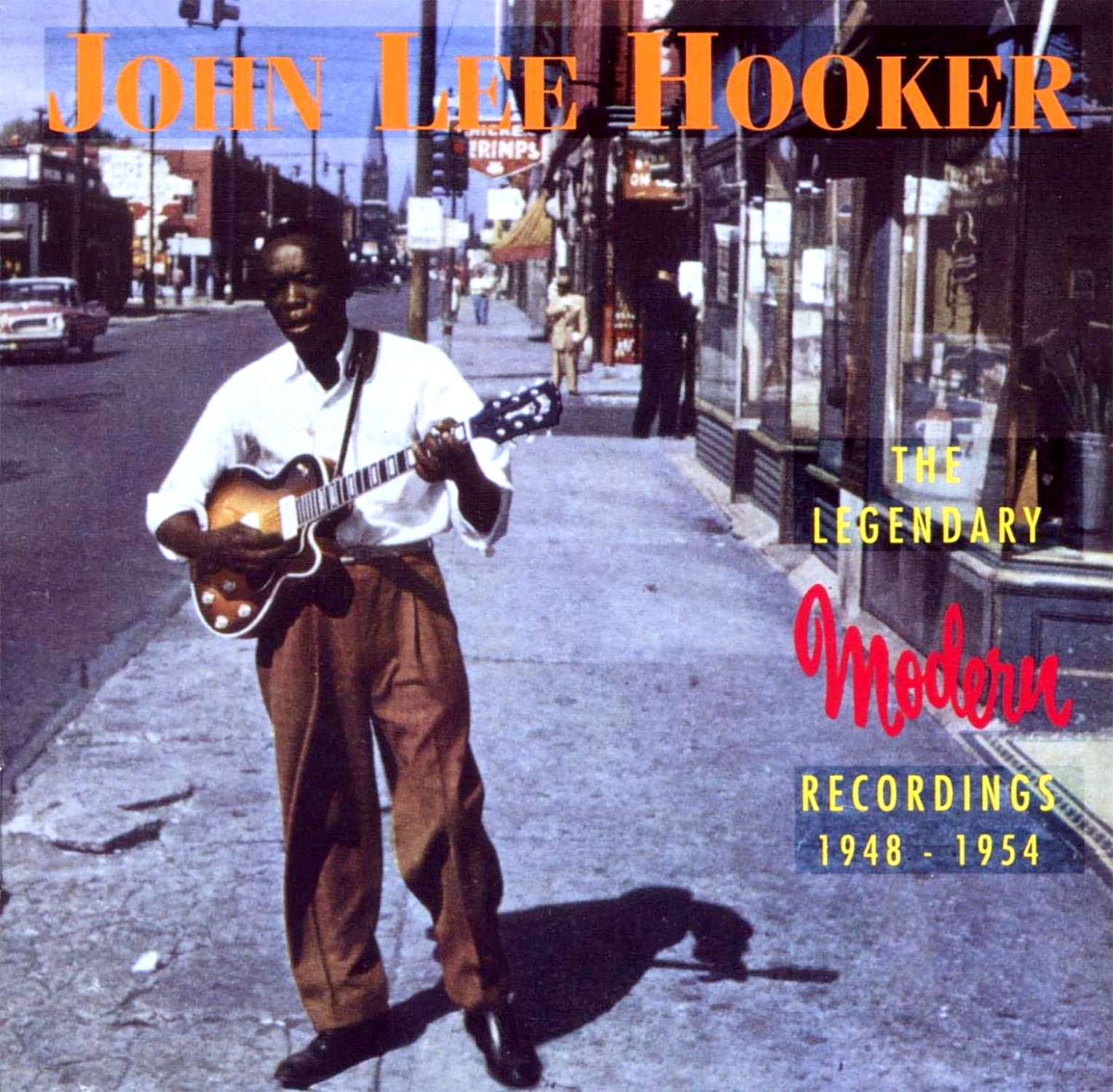

Hooker is standing with his guitar in front of Joe Van Battle’s music shop (Battle was the father of well-known Detroiter Marsha Music). Hooker is wearing brown slacks, a tidy white shirt, shiny leather shoes. And yet, he looks lost standing on a patch of the great sea of concrete that was urban Detroit in the late 50s. How did a Delta Blues man end up in the Motor City, anyway?

Every Blues man is, by nature and vocation, a ramblin’ man. And the curse of ramblin’ is that you never quite fit in, wherever you land. Like the electrified, hard-driving blues he played, Hooker was neither fish nor fowl, half Mississippi, half Northern city man. He would spend the last years of his life in Southern California, the final resting place for all people who never quite find their home. As Hooker himself put it once in song:

I aint nothin’ but a country boy

Driftin from town to town

Got no place, oh yeah

to call my home.

But when the riot / rebellion of July 1967 started, Hooker was in Detroit, right there on Hastings Street watching the drama unfold. A couple of days later he wrote a song about it. At least, that’s the way Hooker tells it. Legally speaking, the song is credited to Al Smith, who was both a blues man and, by that time, executive at legendary Vee Jay records. Maybe Smith wrote the song, riffing off a story Hooker told him. Maybe not. John Lee Hooker, as already noted, was not a stickler for accuracy in his accountings of who did what and when. Over the years he made up dozens of different names for himself in order to record versions of his songs with multiple labels. We’ll probably never know the real story of how “The Motor City is Burning” got written and recorded. Whatever the case, Hooker’s rendition of the song, captured and recorded just a few months after the events of the summer of ‘67, feels authentically Hooker. It has his growl. It’s got the hard strumming of his rhythmic guitar playing, the inimitable way he draws out the first syllable of the word “world” in the line “It aint no thing in the world I can do.” It’s a Hooker song.

But it didn’t remain an exclusively Hooker song for long. That’s because another legendary Detroit musical outfit, MC5, recorded a cover in 1969. MC5’s version has every bit of the intensity of Hooker’s original with the addition of a good deal more noise, heavier drums, greater distortion in the guitars. MC5 well understood the hard-rocking, amplified urban version of the blues which Hooker had been developing ever since he moved north.

But what MC5 changed in their version of the song wasn’t just the hardness of the rocking. The understanding of the events of 1967 changed, too. You can hear this in the lyrics. Both songs start out with a simple statement of fact: The Motor City is burning. Oh yes, uh huh, the Motor City is burning. In Hooker’s version, that more or less phenomenological observation is followed up by something subjective. Hooker sings, “It aint no thing in the world that I can do.” This confession of uncertainty and confusion is continued later in the song. After telling us the “it” started on Twelfth and Clairmont, Hooker sings, “I just don’t know what it’s all about,” and then repeats that line a second time, “I don’t know what it’s all about.”

It is precisely those lines that are altered in the MC5 version. Instead of singing, “It aint no thing in the world that I can do,” MC5 sing, “There aint a thing in the world they can do.”[drfn]MC5, “Kick Out The Jams / Motor City Is Burning” (BMI Alstein Music, 1969), produced by Jac Holzman and Bruce Botnick, EK-45648-B.[/drfn] Notice, please, the shift from “I” to “they.” And just in case anyone has missed the point, the MC5 make it quite clear, a few lines later, just who “they” is. The fourth line of the first verse in the MC5 version is “There aint a thing that white society can do.” Along these same lines, in the second verse where Hooker sings of his own ignorance as to the cause of the disturbance, MC5 sing,

It started on 12th Clair Mount that morning

It made the pig cops all jump and shout.

And where Hooker sings,

The fire wagon kept comin’

The snipers just wouldn’t let ‘em put it out,”

MC5 sing,

The fire wagons kept comin’, baby

But the Black Panther Snipers wouldn’t let them put it out.

Finally, in Hooker’s version, the song ends with roughly the same confusion, and the sad resignation, with which it began.

I don’t know what the trouble is,

Hooker sings, in one of his trademark moans,

I can’t stay around to find it out

I don’t know, I don’t know.

MC5 shift the confusion and not-knowing onto the older generation, singing,

Your mama, papa don’t know what the trouble is

You see, they don’t know what it’s all about

I said, your mama, papa don’t know what the trouble is, baby. They just can’t see what it’s all about.

The suggestion is obviously that the members of MC5 (in contrast to their parents, and even John Lee Hooker himself) very much do get what it’s all about. Near the end of the song, the MC5 lyrics become,

Now, I guess it’s true

I’d just like to strike a match for freedom myself

I may be a white boy, but I can be bad, too

Yes, it’s true now, yes, it’s true now.

MC5 end the song with “Let it all burn, let it all burn, let it all burn,” whereas Hooker ends with, “Look, get outta here / it’s too hot.”

Thus we find ourselves in a rather strange situation. We have a song, written by a Black man from the Deep South about a conflagration that engulfed the city of Detroit. In his song, the Black man from Mississippi expresses bewilderment about the events he is witnessing. Then, a year or so later, a group of White musicians take up the song and recast it in explicitly racial / political terms. MC5 argue in the song that the events of ‘67 should be seen as a Black rebellion against oppressive white society.

What does this tell us about Detroit 1967? There is, of course, no definitive answer to that question. But the curious transformation of “Motor City is Burning” as it passed from John Lee Hooker to MC5 allows us, if nothing else, to think a bit more deeply about the blues and what it tells us about the exigencies of human experience. I think, specifically, of something Stanley Crouch wrote in an essay he delivered as a lecture at Michigan State University in 1995. In that essay / lecture are the words, “The blues is a music about human will and human frailty […] which is why I say it has a tragic base.”[drfn]Stanley Crouch, “Blues To Be Constitutional [1995],” Considering Genius: Writings on Jazz (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2009), 171.[/drfn]

The blues, according to Crouch, is a fundamentally tragic art form. But we have to be careful with the word “tragedy.” We don’t want to fall into one trap of the blues, which is to see in it only gloominess and despair. As Crouch writes a couple of lines earlier, “you play the blues to rid yourself of the blues.” So there is hope in the blues. There is joy in the blues, great joy. As Albert Murray wrote in Stomping the Blues, “the irrepressible joyousness, the downright exhilaration, the rapturous delight in sheer physical existence, like the elegant jocularity and hearty nonsense that are no less characteristic of blues music, are unsurpassed by any other dance music in the world.”[drfn]Albert Murray, Stomping the Blues (Boston: Da Capo Press, 1976), 20.[/drfn] The blues, in short, is as much for dancing and carrying on as lamenting. And yet it is, for all that, a tragic art form. What does it mean for a joyful art form to have a tragic base?

It must have something to do with this unstable compound that Crouch puts together in the above quote, the compound that joins human will with human frailty. Another way to say this is that human beings are possessed of a great deal of desire and limited means by which to realize that desire. That’s tragedy par excellence. It’s tragic because it is structural. The blues, throughout its history, has captured this structural aspect of human tragedy in the form of love songs. The way the blues tells it, the trouble with love is that it cannot be forced, which often results in heartache (or imprisonment, or death) for one or more of the parties involved. Here’s how Bessie Smith puts it in “Down Hearted Blues”:

Gee, but it’s hard to love someone

When that someone don’t love you

I’m so disgusted, heartbroken, too

I’ve got those down-hearted blues. [drfn]Bessie Smith, “Downhearted Blues,” Columbia Records, 1923.[/drfn]

But love (love lost, love never found, love denied) is often just a vehicle for reflections on human tragedy in all forms. As Cornel West once put it in an interview, “The blues is an autobiographical chronicle of a personal catastrophe expressed lyrically and endured with grace and dignity. Meaning what? Meaning that the blues are all those who are willing to look unflinchingly at catastrophic conditions.”[drfn]Cornel West and Jake Uitti, “Strength in The Blues - An Interview with Cornel West,” The Monarch Review (September 9, 2012), http://www.themonarchreview.org/cornel-west-strength-in-the-blues/[/drfn] Once you start looking unflinchingly at catastrophic conditions, you find them everywhere.

The alchemy performed by the blues is to transform that structural problem, the catastrophes of life bound up with the misfortune simply of being human, into music, and therefore into some form of release. The very act of singing one’s heartache seems to be a partial cure (partial because there is no “total cure” for the human condition other than death). You could say, then, that the blues is the African-American homebrewed version of Freud’s talking cure. It is the modern American version of the same weeping and wailing and catharsis that acts itself out in the Psalms.

To remain silent in the face of tragedy is to be defeated by it. To raise up the voice in lament is to gain some purchase on the depression that would otherwise be overwhelming. Picture, if you will, the sulking angel in Durer’s famous woodcut Melancholia I, 1514, suddenly standing up amidst the discarded tools around her and wailing out, like Bessie Smith, the following lines from the end of “Down Hearted Blues”:

It may be a week, it may be a month or two

It may be a week, it may be a month or two

But the day you quit me honey, it’s coming home to you.

It is hard to imagine Durer’s angel moping around in a funk for much longer after that.

There’s suffering in the deep moan of the blues, but a kind of sweetness, too. The moans in Ma Rainey’s “Deep Moaning Blues,” for instance, come from hurt and dejection:

Mmmn, mmmn

Mmmn, mmmn

My bell rang this morning, didn’t know which way to go

My bell rang this morning, didn’t know which way to go

I had the blues so bad

I sit right down on my floor.[drfn]Ma Rainey, “Deep Moaning Blues/Travelling Blues,” Paramount, 1949, 14011.[/drfn]

They are hard moans. But they also contain hints of the church choir, the Greek chorus, African tribal harmonies. Those moans are uplifting, consoling even as they give expression to the pain at their source.

The moaning acknowledges the pain but also takes ownership of it. Rainey doesn’t try to push the hurt away, she just sits down on the floor and cries. Furthermore, it should be noted that in Ma Rainey’s “Deep Moaning Blues” there is no lesson learned. That’s to say, her Daddy has stayed out all night and she never figures out why or, more importantly, what to do in order to prevent the situation from happening again. Daddy may very well stay out too late every night for the rest of the month. Surely, he’ll do it again soon.

I felt like going on the mountain, jumping over in the sea

I felt like going in the mountain, jumping over in the sea

When my Daddy stay out late he don’t care a thing for me

Mmmnn, mmmn

Mmmmn, mmmn

Daddy, daddy, please come home to me

Daddy, daddy, please come home to me

I’m on my way, crazy as I can be

The lyrics, in typical blues fashion, reveal very little about the situation. But it’s enough. The timbre of Rainey’s incredible voice does the rest. We feel and understand and commiserate with Rainey’s condition without ever pretending to understand why lovers can be so selfish, can be so bad to one another. Rainey gives us emotional understanding of her predicament without ever considering that an intellectual understanding could or should be provided. Rationalizing is not what the blues is for.

Let’s take another song. This is “High Water Everywhere” by the great early Delta blues man Charley Patton. Here are some of the lyrics to the song, which are sung with a great deal of that inimitable Patton pathos, the disarming sound of which is difficult to describe:

Well, backwater done rose all around Sumner now

Drove me down the line

Backwater done rose at Sumner

Drove poor Charley down the line

Lord, I’ll tell the world the water

Done crept through this town

Lord, the whole round country

Lord, river has overflowed

Lord, the whole round country

Man, is overflowed

You know I can’t stay here

I’ll go where it’s high, boy

I would go to the hilly country

But, they got me barred

...

I am goin’ up that water

Where lands don’t never flow

Well, I’m goin’ over the hill where

Water, oh don’t ever flow

Boy, hit Sharkey County and everything was down in Stovall

But, that whole county was leavin’

Over that Tallahatchie shore

Boy, went to Tallahatchie and got it over there.

The song is about a massive flood that struck the area around Greenville, Mississippi in 1927. The flood, and its attendant social upheaval, led to a great deal of racial strife in the area and the murder of an innocent black man by a National Guard member. But Patton addresses none of that in his song. Robert Palmer explained why this might have been the case in his book Deep Blues:

[T]here is a sense of fear and confusion in “High Water Everywhere,” and in the second part of the performance, which finds Patton groaning like an evangelist as he describes the plight of the flood victims, there is compassion. It’s possible that verses critical of the whites’ relief effort did not get recorded, but it seems more likely that Patton sang about fear, confusion, and compassion simply because those were the emotions he felt at the time.

The blues deals with fear, confusion, and compassion not by trying to get distance from such emotions but by diving deeper in. The motivation behind singing the blues, wrote Ralph Ellison, is “an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.”[drfn]Robert Palmer, Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta (New York: Penguin, 1981), 75-6.[/drfn]

John Lee Hooker was no fool. He was perfectly aware of the racism in 1960’s Detroit. He was aware of the class struggle. But he was also a singer of the blues. When he sang “Motor City is Burning,” he was trying to hold close to the pain and confusion of the event. It was scary and bewildering (and probably also exhilarating, as the MC5 would have it) to be in Detroit in the summer of 1967. The meaning of the Detroit rebellion of 1967 continues to be fought over, debated, wrangled with. But the blues, as it was played and sung in 20th century America, was not designed to engage in such debates. It was designed to honor the raw forms of experience that come before deliberation. It was designed to transmute into words and sounds the kind of knowing that comes before understanding. The blues, as Ellison reminds us, is not the consolation of philosophy. It is, instead, a mournful and joyful stomping that faces tragedy head on and refuses to be bowed down.

“Don’t ya know the Big D is burnin’,” John Lee Hooker sang. “Aint no thing in the world that Johnny can do.”