Envoi - Brief Readings, or,

thinking through new times

It is our sorrow. Shall it melt? Ah, water

Would gush, flush, green these mountains and these valleys,

And we rebuild our cities, not dream of islands.

Auden, “Hearing of harvests rotting in the valleys”

Maggie Nelson. On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2021. 288 pp.

Emma Dowling. The Care Crisis. London: Verso, 2021. 250 pp.

The Care Collective. The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence. London: Verso, 2020. 114 pp.

The Politics of Care: From COVID-19 to Black Lives Matter. Ed. Deborah Chasman and Joshua Cohen. Boston: Boston Review, and London: Verso Books, 2020. 216 pp.

The Pirate Care Project. https://pirate.care/pages/concept/

Pirate Care is convened by Valeria Graziano, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak.

Pirate Care is a transnational research project and a network of activists, scholars and practitioners who stand against the criminalization of solidarity & for a common care infrastructure.

Care is everywhere, and everywhere marked by its absence. Hardly a week goes by without a friend sending me yet another reference to a new book or pamphlet on care. Since there is not only an ethic and politics of care but also, increasingly, an aesthetic of care, Maggie Nelson thinks it is worth challenging what is at stake in the new pervasive obsession with care, since who would think care a bad thing – but Maggie Nelson does not do warm and fuzzy, and in her own way she arrives at, but without channeling, Martin Heidegger (The Essence of Truth) and Orlando Patterson (Freedom, vol. 11For the longest time, imagine, I wondered what happened to volume 2 of this book!

In March 2020, as American society began to accept that there was indeed something out there from which it was worth sheltering, I was, wouldn’t you know, teaching a class on Care of the City through an introduction to the feminist ethic of care tradition. It was straightforward to get students to grasp the significance of the gender and neglect of care practices, grosso modo, both receiving care and care-giving – of the body, the child, the house, environments, working with the routines which are the bases of larger habituations which establish spaces as livable or as sanctuaries, such care being the basis of images of relationships, and also (ultimately?) the City to which in certain moments of crisis we relate as a body in need of care, that is, presence, time, for which the work of the hands becomes a metonym. We even came to understand that we can care for strangers in a way which, say, and with all due respect to Senator Cory Booker’s Democratic Presidential Primary run, one cannot love whom or what we do not know. It was relatively easy, even, to grasp that gendered caring practices were, following Selma James and Sylvia Federici, a form of invisible work which erased itself as soon as it was accomplished3It is not difficult to grasp how performance art could make the everyday a subject of art and so invite viewers (or participants) to enact the … thereby providing an image of why it was difficult to get society to accept that housework should be paid work (very few students would accept this proposal), that the unpaid care that went into the work of habits (housework) was the basis without which economies would collapse. What was more challenging, however, was moving away from voluntarist thinking – I choose to care; I do not choose to care because … - to a mode of thought where to care was not a choice, the position of Heidegger’s ontological conception of care, which is the basis for a mode of thinking of Care as response to the threat or fact of broken sociality, indeed, of broken sociality as an instance of retrait - retreat, withdrawal, voiding, collapsing, even dis-investment (in both the colloquial and analytic sense of this last term). Then came COVID-19 and the anxiety of what Heidegger characterizes as the collapse of familiarity, that is, the everyday, and the anxiety, that is, Care, induced by the confrontation with the loss of what is normally taken for granted. It is here that it is essential to be reminded of the Germanic etymology of the English care. The standard etymology of the English word care (from a current writer such as Anatoly Liberman all the way back to Skeats) points to “Anxiety, sorrow,” heedfulness, attention, even to lament, or to sorrow (“wholly unconnected with Latin cūra, with which it is often confounded,” say most dictionaries of etymology). So, the English care has built into its latencies and historical sedimentation the idea of grieving, or sorrowing for that for which one cares: the frail body of the loved one, the body about to depart for distant travels which induces melancholy and vague anxieties centered on the possibility of the non-return of the loved one, which may also be an image for, or a way of proleptically living the absence of. the body about to depart this world, the body incapacitated and thus utterly dependent upon the caring relation, that is, the relation of attentiveness, heedfulness, underwrit by a certain anxiety or anguish. Grief, however, collapses the grieving self and not necessarily because of what is already proximate to the one who grieves – and this is Heidegger’s insight into the non-voluntaristic dimension of Care, the ontology of Care, without which, the demand for care – also the demand for attention – is indistinguishable, and tellingly so, from a demand for love. …And so COVID becomes the home for the greatest drama of attending that we have all witnessed in our recent cultural memory, the murder of George Floyd, a graphic drama in the literal sense –- and here, I happened to be reflecting on a set of photographs on The Confederate Monument in the American South which my colleague Carlos Diaz had been developing for a book over a number of years, the opening of which, my response to seeing these photographs during COVID-19 and the murder of George Floyd, I reproduce here as it allowed me to think the relation between image and suffering, care and the collapse of familiarity, as well as image and mimetic desire in a framework where repression is the form under which things can be hidden – and disavowed – in plain sight.

1. “The time is out of joint.” Hamlet, 1. v. 188.

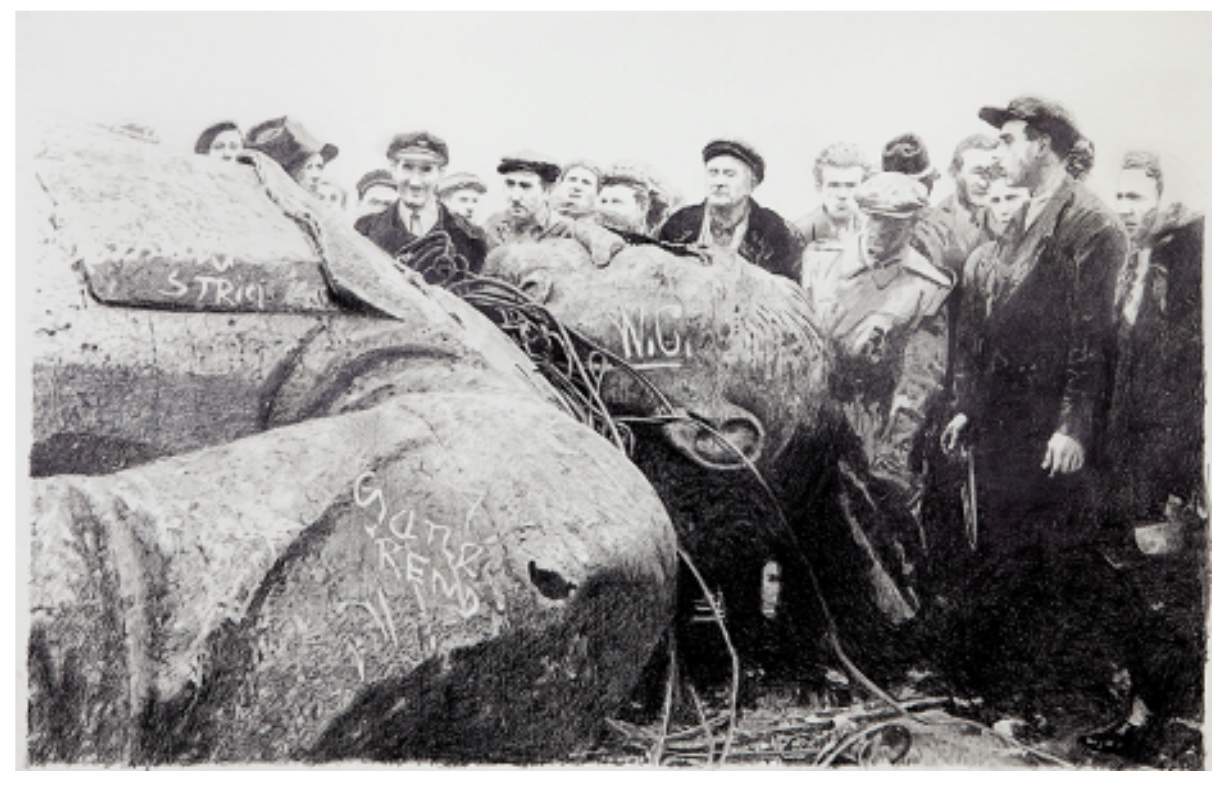

When, just over a year ago, Carlos Diaz, the author of this collection of photographs, The Confederate Monument in the American South, came by my office in the College for Creative Studies in Detroit where we both teach and asked if I might be interested in writing an essay to accompany the work, I jumped at the opportunity not only to work with a photographer whose work I had come to admire but because I was very recently back from my first visit to Richmond, Virginia, which is also to say, I had been taken, as is every first-time visitor to Richmond, to Monument Avenue to see the collection of Confederate Monuments – and more thought needs to be devoted to this word collection and the phenomena which it evokes and shelters. I had never seen anything of the kind anywhere in my life! Parisians must be tired of the visitor’s response to La Tour Eiffel, just as many in New York are utterly unfazed by the Empire State Building – even after Jay Z and Alicia Keys’ “Empire State of Mind” – or many in Detroit are politely bored by the many visitors who are awed by the ruins of the Michigan Central Train Station, but during my stay in Richmond I do not recall anything blasé in anyone’s conversation about the statuary on Monument Avenue and this was not surprising for the city that had once been the capital of the Confederacy is now a bastion of liberal and progressive wealth and privilege, and just as no one could ignore the monuments no talk could not be also simultaneously about the question of the monuments: the entangled politics of their afterlife, the complex ethics of aggression and impotence entailed in their cast shadows, and their continued injury to thought. If, after the collapse of Communism and the Warsaw Pact as symbolized by the Berlin Wall, the world had become accustomed to the idea that with the collapse of a governing order goes also the monuments to its own magnificence – something repeated and televised the world over with the collapse of the regime of Saddam Hussein – then it must seem all the more jarring and discomfiting to encounter the phenomenon of the Confederate Monument in the American South: Everywhere else in the modern and contemporary world the monuments of losing regimes in Budapest, Hungry (1956), in Accra, Ghana (1966), in Tehran, Iran (1979), in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (1991) – and no regime loses because it is good or virtuous – are by popular assent pulled down, dragged off, and melted or broken down or, as with the recent pulling down of the statue of the British slave trader Edward Colston in the English port city of Bristol, thrown into rivers or oceans - or occasionally put into museums as apotropaic objects: Look on this and shudder!4In the series collectively known as Iconoclasm from 2018, Sam Durant of CalArts composed a set of large-scale grisaille drawings, on the scale of …

2. “Be you my time,” Troilus and Cressida, I. iii. 313.

And there it might have stayed, the cultural version of treading water – until, that is, everything changed, and with a speed, a temporality, a (biblical) suddenness that no one could have imagined as decaying but still resistant values suddenly could no longer temper or deflect the counter-movements of long suppressed histories and repressed psychic injuries. First, it must be said, that the phenomenon of COVID-19 induced something that the world has not experienced at least since 1918, that is, since the time of the Spanish Flu, something that even the direst events of economic collapse cannot ensure, namely, shared experiences of exposure and vulnerability. Every natural or quasi-natural disaster that one can think of from the meltdown of the nuclear reactor in Fukushima, Japan to New Orleans and Katrina or the astonishing gun violence on the south and west sides of Chicago is a disaster from which the rest of society can be sheltered, or, the disaster being elsewhere leaves all else intact and life as usual may continue as usual, but with the phenomenon of COVID-19 a new temporality joins the world and joins together all the intervening moments of separation and differentiation as the disaster envelops every neighborhood – state – country – continent such that, suddenly, with the collapse of familiarity, that is, the collapse of the everyday and life as usual, the shared sense of exposure and vulnerability compels the recognition and adoption of practices of care that many had thought previously were acts of benevolence toward the less well-off either at home or abroad. Care, says Martin Heidegger, is the response to the radical anxiety confronted with collapse of familiarity, the moment in which the human creature realizes that it is a creature (or phenomenon) of care which it has failed to realize because of the distortions inherent to everyday life obstructing its potentiality for being-in-the-world. Care, in this sense, is not a choice (I do not choose to care or not) and becomes overwhelming as when in the phenomenon of radical exposure we begin to realize our consonance with what is not-us, not only fellow human creatures but other bodies, selves, and environments which make for our life-worlds and particular forms of life now grasped as vulnerable and hence in need of care – an ethic and politics of care. Retreating from this collapse entailed a new kind of temporality, a new awareness of care where suddenly the need to care – that is, something no longer a choice or moment of generosity – reveals our entanglements as this term is understood in contemporary anthropology, that is, beyond our mutual inter-relations or symbioses, entanglement is a structure of mutual dependencies. Suddenly the entanglements extending from my home and neighborhood that make my existence depend on the communications system, on the global systems for food distribution and much more are made manifest through their absence as my autonomy, or sense or claim of autonomy, is shown to be no more than my projection of power made all the more risible in my need for others and relations and practices of the everyday. If no one can work at the supermarkets I cannot buy food. If schools and nurseries for my children are closed, I cannot go to work. If no one will work in the hospitals, then…and so on. We have come to apply the military term frontline to such workers, and of course who is a frontline worker is often a function of class and privilege and racial histories. Within this radical exposure, this vulnerability, and compromised sense of autonomy, within, in other words, this phenomenon of dependency so alien to most citizens of the United States, comes the most extraordinary image of human pain, suffering, and degradation articulated simultaneously as an image of human depravity and monstrosity: the killing, the very slow yet inevitable killing (like a disease finding its prey), as captured on multiple phone videos, of George Floyd at the hands of the white police officer Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, as Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes 46 seconds, ignoring Floyd’s pleas of “I can’t breathe!”

3. “For thy records, and what we see, doth lie.” Shakespeare’s Sonnets, 123.

The killing of George Floyd changes the temporality of social and political life in the USA; indeed, the temporality of the social and political processes is made possible by, and follows the temporality of, COVID-19. Above I spoke of the image of human pain and the image of human depravity, and I do not intend this sense of image, the weight to be borne by the term, in any casual sense, for I mean precisely to say that the suffering is articulated as part of an economy of visuality and it is precisely because there is a vast and complex network and system of circulation for the recording, disseminating, and sharing of images – an economy of visuality – that it will become possible for the attention of Americans and the world (a contemporary world composed of afferent networks leading from and back to the United States of America in banking, economy, the military, politics, and culture) to be simultaneously and spontaneously shared as condition of mimetic behavior. The commanding and magnification of attention by the material infrastructure of image-circulation, the photo-graphic condition of contemporary communication(s), in other words, après-coup provides a genealogical structure (what Michel Foucault understood by the law of the archive, which is not simply a collection of things but a principle of inevitability of power) for visualizing affect and replication of the same (think Eric Garner’s I can’t breathe, say, as announcing the work and structure of inevitable power when repeated by George Floyd’s I can’t breathe at which point it becomes an archive of inevitability; or the artist Dread Scott’s flag A Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday, 2015 announcing a similar archive of inevitability in light of the NAACP’s banner A Man Was Lynched Yesterday [NAACP headquarters in midtown, Manhattan, 1920 - 1938]. Grasping the instance, the practice of the replication of the same is also a grasping of the moment of the instantiation of the law of the archive, as if, in our example, the photography of lynching as conveyed in the NAACP banner A Man Was Lynched Yesterday – for here we do not need to see the photographs and postcards of lynched bodies5Photography is part-and-parcel of the circulation of suffering, of the figuring of social pain. It is, one might say, an anthropological condition: … - is at one with, and part of the same economy as, the institution of the American Confederate Monument by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (see the Confederate Dead in Shiloh, Mississippi, 1957). The time of George Floyd’s killing is the psychic and cultural time which allowed the photo-graphic conditions of black pain to be receivable, and why the contestation called Black Lives Matter, following the killing of George Floyd, had to be in the media of visuality at the same time that the photo-graphic capture of suffering had to be opposed by many as another form of pain - here one may think of Claude Lanzmann’s unconditional refusal to use a single photo-graphic document from the Nazi concentration camps in any of his film work but most famously Shoah (1985), and one may think also of the way in which the photo-graphic depiction of Black suffering and death has become a target of activist refusal even as such visuality has become both evidence (of a past event) and affect (repetition in the present). As the anthropologists Arthur Kleinman and Joan Kleinman comment:

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience; it is a defining quality, a

limiting experience in human conditions. It is also a master subject of our mediatized times.

[…] Images of suffering are appropriated to appeal emotionally and morally both to global

audiences and to local populations. Indeed, those images have become an important part

of the media.6Arthur Kleinman and Joan Kleinman, “The Appeal of Experience; The Dismay of Images: Cultural Appropriations of Suffering in Our Times,” in Social …

In the current moment following George Floyd’s killing and in the media which made that transmission of affect possible, the photographic and digital media of replication, there followed not simple denunciation – swift and uniform, even from police unions – but, more significantly, a lifting of (social and cultural) repression, a negation of the iconography and monuments of surreptitious power (now grasped as symptoms) created by or associated with the United Daughters of the Confederacy and their allies: in Richmond, Virginia, in the State Capitol of Kentucky, in Little Rock, Arkansas, in Houston, in Oklahoma, in Tennessee (where Taylor Swift declared that confederate Monuments make her sick, and where others have proposed in a Change,org petition that images of “a true Tennessee hero,” Dolly Parton, replace Confederate Monuments). Confederate Monuments which have not been pulled down have been defaced in a way that the new visual and cultural and political meanings produced can never be reversed even if all such surviving monuments could be cleaned. It is as if, in the time of the photo-graphic conditions of George Floyd’s killing, the lifting of (social and cultural) repression allowed something important to be seen about the anthropology of lynching and the species of memorializing practiced by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in their building of Monuments, for all anthropology is fundamentally a question of equivalence: for as many white Confederates who died in the Civil War there should be as many Black bodies. The acts of memorialization and monumentalization are undertaken jointly in the name of: those who died defending the Confederate Cause and, through (anthropological) entanglement, those who would be liberated from that same Confederate Cause. These Monuments, then, are of the Confederacy but for Black bodies. Within the structure of unconscious thought this is what is meant by disavowal in psycho-analysis: the denial of what is perceptually present so that in repression the thing denied by the mind can fulfill more than one purpose at the level of the unconscious. It is, too, the unconscious anthropological truth un-concealed in the image and time of the killing of George Floyd.

A recognition of this equation has long informed the (philosophical) anthropological reflection of Southern American murderousness toward its Black population. Jack Kerouac, for example, in his prose-poetic introduction to Robert Frank’s epoch-defining photographic collection Les Américains (Paris, 1958 and as The Americans, New York 1959), the most telling aspect of which is the racism that is part-and-parcel of the American atmosphere, would write very simply: “Man, black, mad mourners […] and death is like life, what else?” The French film-maker and critical theorist, Guy Debord, writing in 1966 in an extraordinary reflection upon the Los Angeles Watts riot of 1965, could articulate the insight of America’s problem by first observing that “It is no longer the crisis of the status of Blacks in America; it is the crisis of the status of America, posed at first through Black people.” (“Le Declin at chute de l’économie spectaculaire-marchande,” Internationale situationniste, no. 10 (Mars 1966): 4.) Wherever a group or population becomes a “problem” of the genre What is to be done with the Jews? What is to be done with the Negros? What is to be done with the Native Americans / Kulaks / Uighers? the problem is not this particular group of people but a psychotic kernel within a dominant mode or form of life that seeks a sacrificial victim in the targeted group, hence Debord will write that “[Blacks] are disfavored from the start,” and in this sacrificial role allotted to them – the great Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson says nothing more than this in his important if somewhat neglected book Rituals of Blood, 1999 – as a population “Blacks as a whole must represent the poverty of a society of hierarchized wealth.” (Debord, “Le Declin et chute de l’économie spectaculaire-marchande,” 7). The great American essayist Elizabeth Hardwick articulated a structurally comparable insight – what it is that the Negro represents as a means of giving form to the psychotic kernel in American culture – when, also writing of the Watts riots of 1965, she observed: “We know that only the severest concentration will keep the claims of the Negro alive in America, because he represents all the imponderables of life itself.”7Elizabeth Hardwick, “After Watts” (1966), in The Collected Essays (New York: NYRB, 2017), 154. My italics. One could write an essay, a long commentary just on this sentence, but suffice it that Hardwick’s formulation allows the reader to grasp that there is a question, an ethics of attention – the severest concentration – that allows one to begin to grasp and to formulate a response to the question being posed everywhere after the outpouring of affect following George Floyd’s killing, after the sudden and radical change in American sympathy for the commitments and language of Black Lives Matter, as well as the contingency of sympathy, namely the question, Why now? Why now when so much has already been visually and in real time documented? Why now since we need to know so that we might know how to sustain the change or, at the very least, prepare for another (unanticipated) change? It would not be an exaggeration to say that for many in the activist community there is almost a trauma, an unacceptable uncertainty around the question, Why now? Hardwick’s formulation says that it is indeed a question of attention and attention of a kind that is not normal – and maybe no longer normative – namely, attention that is severe and concentrated, in other words, durational and embodied, not fleeting, above all not an avoidance. Hardwick was very familiar with the thought of Simone Weil for whom attention was the opening not only to suffering but to divinity. (There is an intimate relation between attention and hospitality as Weil realized. In the ancient tradition, as found in The Odyssey and the Gospel according to Matthew, hospitality is conceived as something divine. There are many ways of conceiving the question of the human but a central way passes through the issue of who is deserving of attention, care, and hospitality, and thereby, in this tradition, who participates in the divine.) For Weil the full exercise of what it is to be human is available only in the act of attention where, on Weil’s argument, the object of attention is independent of the attending subject for “Attention consists in suspending thought, leaving it available, empty and ready to be entered by its object […] thought must be empty, waiting, seeking nothing, but ready to receive in its naked truth the object that is about to penetrate it.”8Simone Weil, quoted in Joan Tronto, Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care (New York and London: Routledge, 1994), 128. The importance here of the autonomy of the object of attention is that “When one is attentive to the object, one is no longer paying attention to oneself,” writes Weil in a set of notes to herself, and this paves the way for one of her characteristic formulations in which she writes (in a manner that anticipates the work of Jacques Derrida on the impossibility of forgiveness) that attention “is contemplating the non-contemplatable.”9Simone Weil, Oeuvres complètes (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), VI.2: 419. Here is the context:

Contemplating the pain [or affliction] of others without allowing the act of looking to be distracted: not only the act of looking with eyes, but also without unsettling the act [or look] of attention through revulsion, or sadism, or through any kind of psychological consolation. That is beautiful. For that it is contemplating the non-contemplatable.10Weil, ibid, 418-419.

What is the graphic transmission of George Floyd’s killing if not contemplating the non-contemplatable? If this passage has echoes of Susan Sontag’s critique of photography in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003) this is not an accident for Sontag, like her friend Elizabeth Hardwick, draws upon Simone Weil, in arguing against the photo-graphic capture of experience that it is only if we can attend with sufficient concentration - destroy the idolatry of the image after using it as a starting point11There is every reason. For instance, to believe that Robert Frank’s practice has built into it an attack on the idolatry of the image in relation … - that we might be able (a) to avoid voyeurism and (b) to assume onto ourselves the pain and affliction of others, something less and less possible in a condition where one population has had enforced on it the social status of, or come to “represent all the imponderables of life itself.” It is, says, Hardwick, the unknown imponderables (in my diction, the unconscious psychotic kernel) which distract attention thereby necessitating the heroic, the severest concentration.

Gilbert Ryle, brisk as only the English can be, but also an early commentator on Heidegger’s Being and Time, perhaps the first in English-language philosophy of a major order: “To take care entails being prepared for certain sorts of emergencies.”12Gilbert Ryle, The Concept of Mind (1949) (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1978), 134. My emphasis.

Wilson Harris, in the opening sentence of The Infinite Rehearsal: “Let me begin this fictional autobiography with a confession. The values of a civilization – the hope for a universally just society, for the attainment of the mind and heart of love, the genius of care – are an impossible dream…”13Wilson Harris, The Infinite Rehearsal (London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1978), 1.

We now have many names for emergencies but Care has emerged as the indispensable name.

La Librairie de Guy Debord: Stratégie. Ed. Laurence Le Bras. Paris: Éditions l’Échappée, 2018. 525 pp.

La Librairie de Guy Debord: Poésie. Ed. Laurence Le Bras. Paris: Éditions l’Échappée, 2019. 586 pp.

La Librairie de Guy Debord: Marx et Hegel. Ed. Laurence Le Bras. Paris: Éditions l’Échappée, 2021. 521 pp.

La Librairie de Guy Debord: Histoire. Ed. Laurence Le Bras. Paris : Éditions de l’Échappée, 2022. 528 pp. [As DR3 goes to press.]

In 2001, as I was leaving Northwestern University, I wrote and published an essay on “Néo-Stoicisme et éthique de la gloire: Le Baroquisme chez Guy Debord.” Looking over one’s old publications can be a depressing business – especially if one’s writing got caught up in provincial arguments, which mercifully was not the case here14I shall be eternally grateful to the late Malcolm Bowie who, when he read my ms on Voice and the Enigma of Place: On Surrealist Experience, called me … – but I have continued to hold to this essay with only one regret: that a section on “Temps et musique” and a film still (or rather a screen shot) of Guy Debord’s library in the French country side of Champot in the Haute-Loire had to be cut. (Sollers was absolutely right in his film on Debord, Une étrange guerre, to emphasize the essential importance of Baroque music in Debord’s sensibility. There remains a serious reflection to be undertaken on the importance of Baroque music in Debord’s thinking – Not only is the use of Art Blakey’s Whisper not in In girum nocte et consumimur igni (1978) the unique instance of Jazz in Debord’s filmography,15And the melancholy and beautiful composition Whisper not by Art Blakey? A piece of pure nostalgia and commemoration on the part of Debord. Whisper … it is also the unique instance of non-Baroque music, if we accept Michel Corrette, whose Les Délices de la solitude, op. 20, Sonata VI in D Major, we hear in La Société du spectacle, as a composer from the late stage of the Baroque in music, and of the Baroque composers used by Debord, Handel – for his Thèmes cérémonieux des aventures16Cf. Sur le passage de quelques personnes à travers une assez courte unité de temps, 1959, b&w, 35 mm, dir. Guy Debord. – is the only non-French composer: De Lalande, Couperin, Boismortier, and Corrette are the composers whose music we hear in the films of Debord.) Debord’s reading, his culture, is evident at every turn, as is the directedness of that culture, and seeing the photography of Debord’s study in Champot served to cohere in my mind the desire on Debord’s part for a particularity of culture – not the cultivatedness of the average bourgeois.

It’s not long after this moment that a certain chauvinist strain in the American historiography on Debord started to appear emphasizing what it openly characterized as the Americanness of its approach and against what it considered the French approach to Debord, an approach that addressed the melancholy, the revolutionary pessimism, the classicism of his style, the systematicity of this thought (also known as philosophical anthropology), and worst of all, which began to separate Debord “from his colleagues” – what a quaint bit of piousness – in the Internationale situationniste. As the camera pans slowly in its approach to Debord’s country residence where the precious library is held, we hear Sollers in a voice-over reflecting on the role of retrait (withdrawal) and solitude so important to Debord, as he asks: “Seule? Non. La pensée essentielle de la liberté n’est jamais seule? [Alone? No. The essential thought of liberty is never alone!]” - Alas, certain things are simply not egalitarian: beauty, intelligence, good conversation, and style. I still treasure the screen shot of Debord’s library, it may even have been the first screen shot I ever took – I recall watching the film for the first time in 1999 – if I am not mistaken - with a colleague in New York as we worked on a translation of a Debord text, for it was so obvious that Debord’s culture was larger, more generous, and analytically encompassing than the use to which the academic literature of the late 90’s and 2000’s was putting a limited body of his work. The French Debord – well, his library was declared a national treasure and acquired by the State, much to the irritation of certain American admirers – was never, of course, narrow and aetiolated, and since the State – l’État – acquired his library, enormous work, of the kind well-established in French academic culture (see work on the collection of André Breton, but also on the library of Paul Celan) has been accomplished in making public the range and materials and significance of Debord’s culture of which the three volumes of Debord’s (carefully organized) reading notes under consideration are but the latest tranches. Here in these three volumes is all that most of us will ever need to be able to reconstruct Debord’s reading in poetry, Marx and Hegel, and strategy and therefrom draw our own conclusions. Lacenaire is there with Bossuet, La Bible de Sarcy along with poetry from the Tang Dynasty, Boulenger’s Les Romans de la Table Ronde with Gracián, but also Gertrude Stein with Marcel Mouladjil. Indeed, with Goethe, and the strong presence of Pessoa and Machado, one suddenly realizes that we are confronted with a reading in World Literature - the terms of which are wholly based on economies of circulation in translation and power - of a high and distinctive sensibility. In a saying attributed to the iconologist Erwin Panofsky, it is often said that who has the best photographs wins (in art historical research since one cannot physically visit every object of one’s interest), and here we might say, in view of how it is typical of the European avant-garde – Breton, Tzara, for example – that who has the best archives shapes history. The kind of (institutional and historiographic) work represented in these volumes is only possible because of the meticulous archives maintained by these artist-thinkers themselves. I recall reading of Asger Jorn’s arrival in post-World War II Paris and his thinking that Surrealists and former Dadaists and assorted avant-gardists would be into his wish to meet and talk for as long as he wanted to talk – all in the name of spontaneity. He was shocked to find that right across the social and political spectrum French writers and artists kept very strict hours for lunch and dinner since outside these times they were busy making their archives for posterity, something Duchamp helped Enrico Donati to realize when Donati asked him why Breton’s handwriting was always so perfect: PM, Duchamp replied: post-mortum.17I recall as a teenager – who had in any case always written with a Waterman fountain pen – reading of Rilke starting over any letter in which he … Posterity – the transmission of values. As Breton wrote in his “Prolegomena to a Third Manifesto of Surrealism, or Not” (1942): “my greatest ambition would be to allow the theoretical sense to be indefinitely transmissible after me.” This concern with transmission may yet prove to be the lesson of lessons of the historical avant-garde.

Tombeau pour Okwui Enwezor

Okwui Enwezor, et al. Trade Routes: History and Geography. Johannesburg: Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council, 1997. 412 pp.

Okwui Enwezor, et al. Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America. New York: Phaidon and New Museum, 2020. 264 pp.

I would run into Okwui Enwezor (1963 – 2019) in New York. On one such occasion he walked me around his exhibition The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994 (2001, Munich, Museum Villa Stuck). I had missed its Chicago installation and felt that I had lucked out to be walking through the New York iteration of the show with him at MoMA PS1 (2002). He was already a rising star in the curatorial firmament, but after this show, The Short Century, his reputation was firmly and irreversibly established. The catalogue of his which meant most to me was his first great show, Trade Routes, the Johannesburg Biennial, for this exhibition showed the scope and depth of his ambitions, which was never simply to put on Big Shows – the command of resources cannot be ignored; it has in its own right a certain impressiveness – but to take the emerging genre of the project show to a new level where it would explore new epistemological and curatorial models of research and knowledge. It is with the emergence of the ambitious project show that the idea of the star curator is born and with it all the by now well-known clichés about the curator lacking humility, getting in the way of the works, wanting to be considered on a creative par with the artist, etc., etc. Enwezor’s ambition, however, wanted to re-write the DNA of Western ideas of contemporaneity through Art – the capital A is required – in part by refusing to the West the privilege of measure or standard, by compelling a cultural confrontation – hence the prevalence of conflict as substance and framework so frequent in his shows - and not merely some anemic idea of contextualization, and to do so required, necessitated the command of considerable resources, could not, indeed, be an incremental thing. And what luck, the project mode of curating, the exhibition as epistemological model, coincided, post-Warsaw Pact collapse, with the expansion of Western ideas and wealth through globalization, and so both the resources and the infrastructure were available to take on the Western Idea of the order of things, even as new centers – Indonesia, China, Johannesburg, South Korea, Brazil, for example – were entering the fray whether to decenter or to polyphonize the strands of late modernization. This irony cannot be understated. The proliferation of biennials and large project shows was testimony to the wealth of globalization even as the issues of justice both within and beyond the West remained muted by this very wealth - until it didn’t, of course. It needs also to be emphasized, that the wealth of globalization led not only to a proliferation of biennials but a transmutation of art which the academic discipline of art history as traditionally conceived could no longer manage nor conceptualize, and so curatorial practice (research) – and not even museum studies – has become one of the principle means of organizing the contemporaneity of art and its symbolic dissemination. Trade Routes is a materialist articulation of this development. Think Allan Sekula – the analytic capacity of Sekula’s practice - on the ocean as hidden space and the (mostly) hidden role (but hidden from whom?) of the container ship in the development of globalization, the spreading of the modern conditions of production through sea lanes. Trade Routes – Commodification – Spectacular Time. Think John Akomfrah’s Nine Muses (2010) - the poetic capacity of Akomfrah’s practice - also an essay film on the ocean as a language of the human account, whence the ocean / okeanus, as the means by which commodified human bodies are transported to their laboring fate, which, in making Homer’s Odyssey the medium of reflection, confronts the nature of hospitality – this is the main reason why Nine Muses deploys Homer’s Odyssey – or rather the inhospitality confronted by labor built into the foundation of the modern world. We, les nègres, are “Bordeaux and Nantes and Liverpool and New York and San Francisco,” that is, the port cities of modernity, as Césaire’s great poem, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal, says, but each of these cities is also, as part of a poetics and spatial practice, an instance of where arrival is a graveyard as persisting topos for the colonial subjects whose labor, as with all oppressed groups, is the foundation of modernity. So powerful is this hold of the conditions of arrival that in many of the thinkers of Black modernity it has all but achieved the status of phylogenetic inheritance or condition whose urform is the slave ship of the Middle Passage

where the inheritors of the middle passage stewed,

five to a room, still clamped below their hatch,

breeding like felonies,

whose lives revolve round prison, graveyard, church.

The social articulation as architecture of a historical condition is further stated as

Below bent breadfruit trees

in the flat, coloured city, class18My emphasis.

merchant, middleman, magistrate, knight. To go downhill

from here was to ascend.19My emphasis. One is reminded that in Charles Darwin’s title The Descent of Man (a falling away, a moving away from, a decline from) represents an …

The middle passage never guessed its end.

This is the height of poverty

for the desperate and black.20Derek Walcott, “Laventille,” Collected Poems, 1948-1984 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986), 86.

The phylogenetic register is made even clearer and more emphatic when Walcott’s poem speaks of “lives fixed in the unalterable groove / of grinding poverty.”21Walcott, “Laventille,” 88. My emphasis.

One might now understand an Edward (Kamau) Braithwaithe whose poem “Postlude / Home” asks: “Will exile never / end?” or a St-John Perse in whose Anabase (1924) one finds the refrain “L’exil n’est point d’hier! L’exil n’est point d’hier!” (Exile is not of yesterday) for exile, the logic of separation that links departure and arrival, is never definitively overcome, and so the originary moment of in-hospitality upon arrival - a “degraded arrival […] as the beginning […] of our history”22Derek Walcott, “The Muse of History,” What the Twilight Says: Essays (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1998), 41.- is always present trans-generationally because embodied since and in the foundation of the City, that is, the modern world. There is plenty here over which to grieve, and for which one may indeed pronounce many grievances.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America. The title is twice doubling – as if grievance is what comes of (unending or unacknowledged) grief (something built into the etymology of Old French grevance), that is, pain or torment, that grievance is a condition of continuance, “a history of repeated injuries”; as if grief is linked to grievance (as in, file a grievance) and to complaint – plaint: also art song of sadness – of the kind made by working people through their unions against management, but also of the kind made foundationally by elites of self-election in the founding act of separation and birth of this country (the USA) against its monarchical power (see the section of grievances in the Declaration of Independence of which, for example, the grievance against King George “For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world”). The title doubles, also, in grief and mourning. – No matter how often I self-correct, I always need to be reminded that grief, which sounds so physical, so concrete, weighty monosyllable, i.e., Anglo-Saxon as I have learned this, is in fact Latinate, and that to mourn / mourning, which sounds so Latinate to me, is the term etymologically rooted in the Old English, and so also to be reminded that to grieve and to mourn are not simple synonyms – they are synonyms in usage, to be sure – as grief is to be in pain and to mourn is already the ritualized act, the social practice,23See The Metropolitan Museum exhibition, Death becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire, 2015. … of commemorating the pain, of learning to separate oneself from the danger of unending, ceaseless grief. Here we might return – as I returned in my reading and thinking in the temporality of COVID – to the insights of Elizabeth Hardwick shared with Guy Debord, where Debord tellingly observes that that “it is no longer the crisis of the status of Blacks in America; it is the crisis of the status of America, posed at first through Black people,” putting us, says Hardwick, in a condition where one population has had enforced on it the social status of, or come to “represent all the imponderables of life itself.” It is, says, Hardwick, the unknown imponderables (in my diction, the unconscious psychotic kernel) which distract attention thereby necessitating the heroic, the severest concentration. The temporality of Care (Heidegger), the disavowal of what is yet plainly in sight (what I learned from the function of camouflage in Diaz’ The Confederate Monument in the American South at the same time that I was reading Solange Faladé with Stanley Cavell) necessitate violence, but George Floyd’s murder ripped off the illusion in which our sociality is anchored and thereby laid bare the graphic nature of the violence and the role of the victim. Grief / Mourning is thus a calling to make public – to bring to attention is also a mode of caring - what is otherwise privatized pain, since such pain is foundational, not unlike the pain hidden in plain sight in “The Ones Who walk away from Omelas.”

Still, in America… What is the difference between the intense preoccupation with mourning in the 1980’s/1990’s reception of Blanchot, Derrida, and deconstruction and the current preoccupation with Black grief? Is it conceivable that the social and linguistic articulation of Black grief was made possible by the deconstructive discourse of mourning? Still, my question – to myself, obviously – is, What is the difference between the intense preoccupation with mourning in the 1980’s reception of Blanchot, Derrida, and deconstruction and the current preoccupation with Black grief?24Cf. Loss: The Politics of Mourning, ed. David L. Eng and David Kazanjian (Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 2003).There is indeed a difference, and here we may have to await another exhibition, another archeology of curating as we begin to grasp more clearly what was Enwezor and what was - legitimate, let it be said - rather his early heirs, for I comprehend Enwezor, for whom the German language landscape was so very important - see Chris Dercon speaking of “Okwui’s relation to Germany”25Chris Dercon, “Un Bauhaus pour la prévention de la guerre? Ça n’existe pas?” in Anselm Kiefer: Pour Paul Celan (Paris: Rmn-Grand Palais, … - as seeking to grasp and to articulate both the distinctiveness of Blackness in modernity and the challenges of universality, for in mourning no group is unique. The danger constantly skirted in this extraordinary exhibition is that Black grief is Black American grief, that Black grief is in some way unique amongst communal mourning, as if its phenomenology of grief cannot be shareable mourning – to participate is etymologically to share. In the conceptuality of Blanchot, mourning is the condition of being alive in modernity during the afterlife of the holocaust (for which Robert Antelme’s L’Espèce humaine was definitive in Blanchot’s thinking), the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (see here Marguerite Duras’ contribution to the film with Resnais, Hiroshima, mon amour, and her notebooks on La Douleur bearing on the return of her husband Robert Antelme from Buchenwald26Marguerite Duras, La Douleur, in Cahiers de la Guerre et autres textes, ed. Sophie Bogaert and Olivier Corpet (Paris: P.O.L / Imec, 2006), 175-204.), and the technological expansion of power into all aspects of interiority, indeed, destroying even the usefulness of a fiction of interiority, expanding into the feats of post-colonialization. None and nothing can escape this après-coup: “Le désastre prend soin de tout” (the disaster takes care of all) we find in L’Écriture du désastre, hence that limpid statement, also from L’Écriture du désastre [the writing of the disaster]: “Le désastre ruine tout en laissant tout en l’état. (The disaster ruins all leaving all in place [but also: intact].)” And the strangeness of which statement is that we for whom this is become a natal condition may not even recognize it, or feel it as our condition, not unlike the prisoners in Socrates’ allegory of the Cave - which Blanchot would not have used - who have been chained in a cave since childhood and can only see shadows which they take for reality, to which Socrates’ interlocutor, Glaucon, responds, This is a strange image you have shown me and these are strange prisoners, meaning that these are strange prisoners who do not know or are not aware that they are indeed prisoners! The “Allegory of the Cave” is not a Blanchotian image, for sure, but its strangeness, the recognition of which, like a second sailing, comes from the interlocutor, Glaucon, is Blanchotian: something has taken place, something has occurred, which nevertheless would seem – that is, perceptually, phenomenologically, socially – not to have left in its wake any difference: The disaster ruins all leaving all in place, intact. This is something that recent Black American intellectual culture perfectly understands as the non-event of emancipation: the Emancipation Proclamation was enunciated, but it was performatively a non-event. (A statement, Let there be light, is paradigmatically performative, not by virtue of truth or falsity – it can be neither – but by virtue of its utterance leaving a difference in the world.) Saidiya Hartman: “Ultimately, I am trying to grapple with the changes wrought in the social fabric after the abolition of slavery and with the nonevent of emancipation insinuated by the perpetuation of the plantation system and the refiguration of subjection.”27Saidiya V. Hartman, “The Burdened Individuality of Freedom,” Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America … Blanchot’s text further limns this strangeness of the disaster by limning a spectral sociality or infrastructure, for “[the disaster] does not reach such or such, ‘I’ am not under its menace. It is in proportion to the extent that, spared, left aside, the disaster menaces me that it menaces in me that which is outside of me, an other than me which is passively becoming other. There is no reaching the disaster.”28Maurice Blanchot, L’Écriture du désastre (Paris: Gallimard, 1980), 7. Whence, too, this sentence: “Danger que le désastre prenne sens au lieu de prendre corps,” which we might quickly – and hence, provisionally – translate as: “Beware that the disaster should begin to make sense [produce sense?] in place of becoming embodied.” Black grief is nothing if not embodied, but with this show is it in danger of becoming a machine for producing sense? A missing meta-curatorial dimension would have been to include ample materials, doubling the size of the present catalogue as a fitting tribute to Enwezor - letters, emails, provisional lists of artists, drafts, and an accounting of the development of Enwezor’s curatorial practice – to allow a viewer of the exhibition or a reader of the catalogue to construe Enwezor’s part - his fate? - to feel that we have, are confronted with, a tombeau for a compelling and definitive figure of his time, and thus a moment in the transmission of what matters, namely, affect as transmission (de prendre corps: becoming body). It is striking how there is no statement in the accompanying catalogue that is not definitive. Enwezor died just as it became no longer avoidable that the current phase and model of globalization is collapsing like a pyramid scheme. What might an exhibition on mourning in America be that took cognizance of this moment of collapse, retreat, and separation, both analytically and narratively, that is, as a possible opening to an alternative future not predicated on any form of commodification or idolatry of ownership? Or that recognized rage as sorrow (douleur) seeking its practice of mourning (deuil) to eschew reduction to (mere) animality? The model for such questioning, the questioning that puts one’s own being and preconceptions into the experience of doubt, is available in what is likely Enwezor’s most compelling and significant achievement, namely, the plural practice and plural histories of Documenta 11 (2002), and the Documenta Platforms (1-5), but especially Platform 2: Experiments with Truth: Transitional Justice and the Process of Truth and Reconciliation.

Les Magiciens de la terre – Jean-Hubert Martin

Imagine, I was in Paris, Summer of 1989. Recently married. And missed this great exhibition. Chose étrange, it is in Detroit that I meet poets Chris Tysh and George Tysh, who are long-time friends of Jean-Hubert Martin. They introduce me to Martin, whose work I have long admired, and I receive permission to translate whatever I want. So, once more, Detroit, is permissive. After DR3 I shall complete a translation of a text by Martin on the afterlife of Les Magiciens de la terre – as hommage and penance! For DR3, try as I may, I could not look at the texts in the time required for translation – durational and intensive attention - without being overcome by the sense of a missed encounter, for which a book is no substitute. You cannot feel what you have missed and be satisfied with a document. It would be like receiving a photograph edged in black and asking, What’s that?

Solange Faladé and Jacques Lacan

Pour Professeur Ming Tiampo, le 1er novembre XXI

J’ai vu, écrivait ce monstre sacré qu’est Rimbaud;

mais nous, après les autres civilisations,

nous voyons maintenant autrement

du cœur du vivant.

Julien Lenoir

Solange Faladé. Clinique des névroses. Séminaires transcrits par Emmanuel Koerner et Marie-Lise Lauth. Paris: Anthropos, 2003. 349 pp.

Solange Faladé. Le moi et la question du sujet. Séminaire 1988 – 1989. Transcrit par Emmanuel Koerner et Marie-Lise Lauth. Paris : Economica / Anthropos, 2008. 278 pp.

Solange Faladé. Autour de la Chose. Séminaire 1993 – 1994. Transcrit par Emmanuel Koerner et Marie-Lise Lauth. Paris : Economica / Anthropos, 2012. 216 pp.

Solange Adelola Faladé. “Penia et Poros, du récit mythique à l’événement historique,” Psychologie clinique, no. 18 (Winter 2004): 248-254.29This text on “Penia et Poros,” which, in its insistence on jouissance and la Chose, contains the core of a Lacanian account of racism and the …

Solange Faladé. Mandela – De Klerk: Sujets de la science politique. De l’illusion du « même » à la reconnaissance du « semblable. » Collection « École Freudienne. » Vanves : MJW Fédition, 2022. 145 pp. [As DR3 goes to press.]

From the moment that the subject speaks, from the moment that the subject is the

barred subject, from the moment that the subject makes the Grand Autre incomplete,

and when, once again the subject bears, when it makes, a demand to the Grand Autre,

at that very moment there will be created an emptiness [vide], a vacuole in the midst

[au sein] of the Grand Autre, this place which Lacan has called la Chose. The subject is

going to have to find out how to get along with [voisiner] what is forbidden [interdit],

this place of jouissance.30This place of jouissance, which is also a place of suffering.

Solange Faladé, Autour de la Chose, séance du 26 octobre 1993: 15.

One day in August - indeed, the Feast of the Assumption – I chanced upon Solange Faladé (1925 – 2004) and her work. I was floored. I had met Black Lacanian psycho-analysts – one such, Hervé Bouchereau, had included me in an anthology co-edited with my friend Chantal Pontbriand31Cf. Hervé Bouchereau and Chantal Pontbriand, ed. Sur ma manière de travailler (Montréal: Parachute, 2002). - and in any case knew that Latin America and certain parts of Francophone Africa had significant Lacanian thinkers. (Surrealism, Existentialism, and Lacanian psycho-analysis are quite simply cultural touchstones for children of Black and Brown Francophone privilege. C’est la question du père sans doute. Food for thought.) What I did not know - and was deeply puzzled by - was Solange Faladé, this Francophone African woman who was with Lacan from the beginning to the end of his enseignement orale. Delicious confusion of informed ignorance. In an instant, I had a vision of every part of my personal library where I might find her. I started to get up from my writing table, sat down, stood up, then sat back down and decided to scour the internet for several hours and sorted a ton of material of which by far the most important was the discovery of the continued existence of her own school of psycho-analysis, the École freudienne and also Lettres de l’École, the internal volumes of the École Freudienne de Paris, Lacan’s school, of which vol. 25 no. 1 (avril 1979) and 2 (juin 1979) on La Transmission which, I quickly learned, is a term that Faladé had recommended to Lacan to accept - rather than Jacques-Alain Miller’s proposed “tradition” - to address the question of the institutional and pedagogical dimension of psycho-analytic knowledge. I ordered a tranche of books and journals (some of which, six volumes of Lettres de l’École, never arrived in the COVID mail) and rare materials that I could find by Faladé and from what I already knew to be her circle of disciples, students, and friends. From Roudinesco’s La Bataille de cent ans, vol. 2, and the primary documents collected in Claude Dorgeuille’s La Seconde mort de Jacques Lacan: Histoire d’une crise, octobre 1980 – juin 1981, I could begin to assemble a picture of this extraordinary personage and her considerable role within the various aspects of Lacanian pedagogy and institutionality. As her name became quickly associated in my mind with Jean Clavreul and Charles Melman, in other words, as her privileged role in helping to manage the collapse of the Lacanian school, the dissolution, became apparent, I could not stop myself thinking of an extraordinary film – now available online – Emile Weiss’ Quartier Lacan narrated by Alain Didier-Weill, which I was able to watch when it first came out in 2001 and which was always important in my development for introducing me to the voice, the speaking voice of Wladimir Granoff, even though I had long been familiar with his texts and the work of the APF - irony of ironies. In this two-hour film, I now realized, in which Clavreul and Melman played key roles, there is not a single mention of Faladé and I could not fathom why. As the volumes of her Séminaire started to arrive, my puzzlement increased. I started a close reading of Autour de la Chose: it is an introduction to listening to Lacan as Faladé emphasizes attending Lacan’s Séminaire, then a close reading on what is distinctive in Lacan, not, for example, le désir, but la jouissance, a close tracking of the development of Lacan’s reading of Freud in the public of the Séminaire as this opened new pistes, for example, the Entwurf (S.E. I), but also what is on offer in her self-reflexive and self-aware work of the voice is the emergence of a distinctive group in the landscape of 1950s Paris and the French analytic scene participating in a common work – la participation effective au travail de la communauté, as Faladé, Clavreul, and Melman together put it - with a method of reading, and a new mode of listening, and all of it delivered par la voix.32In another context, I think it would be worth pursuing a comparative study of the role of oral transmission in French psycho-analytic contexts … For myself, I quickly discerned a new approach to thinking of racism in terms of disavowal – present in Cavell – in relation to the access to or barring of access to la jouissance autour de la Chose, and the necessity of giving up on the occupation and defense of jouissance. And more, so much more besides.

Michel Parmentier: December 1965 – November 20 1999: A Retrospective. Ed. Guy Massaux. New York: Ortuzar Projects and Paris: Éditions Loevenbruck, 2019. 244 pp.

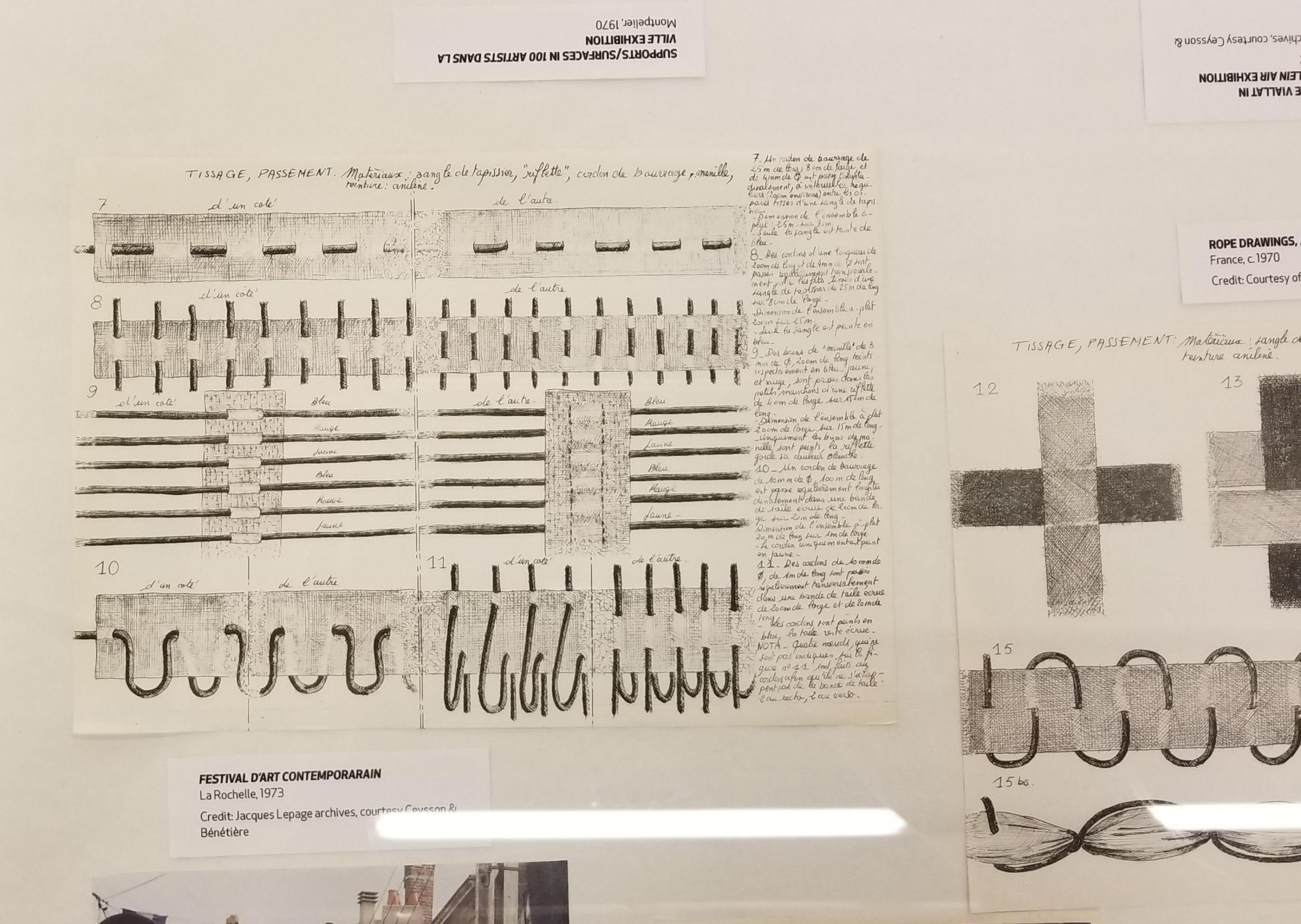

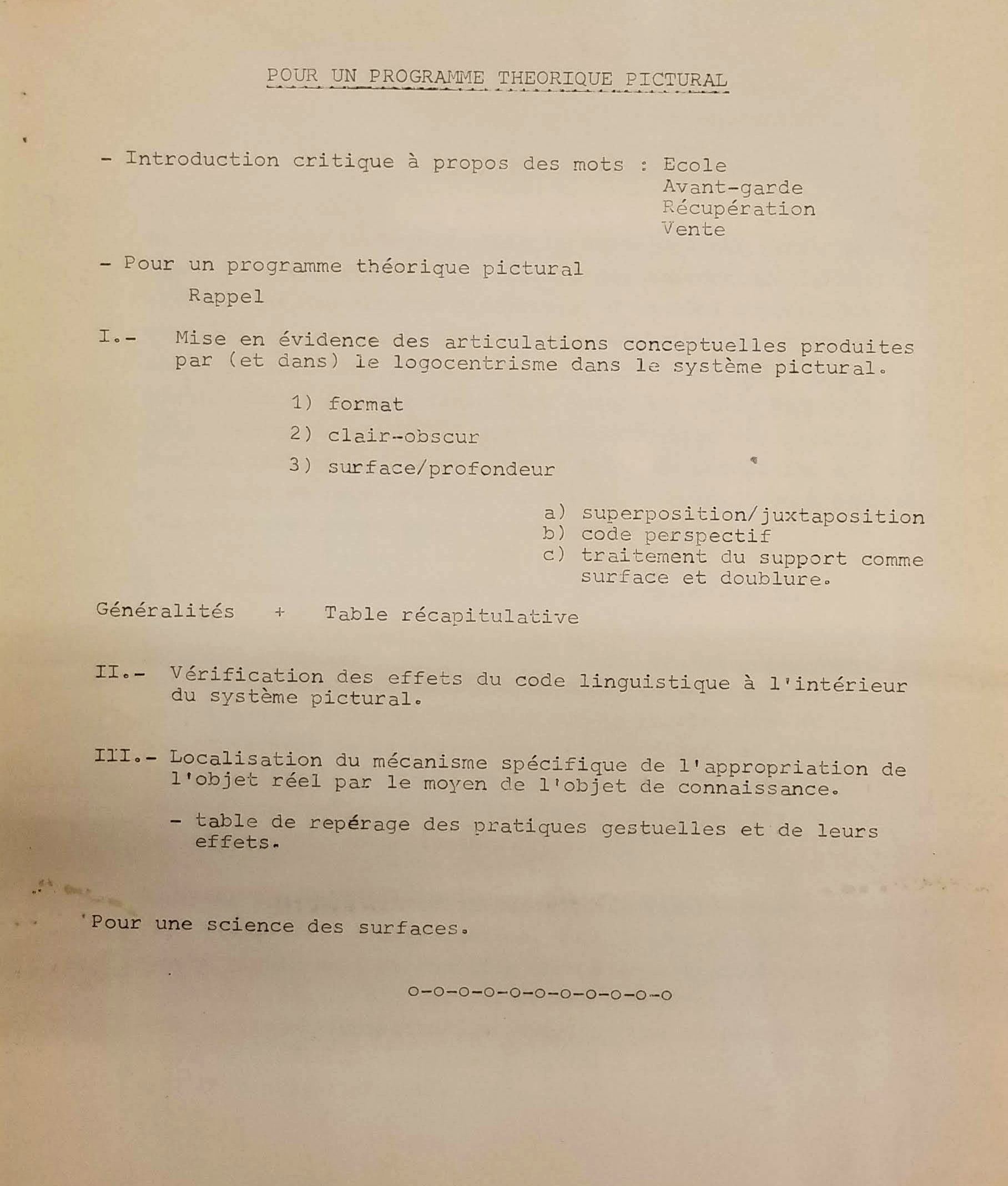

Unfurled: Supports / Surfaces, 1966-1976. Ed. Elysia Borowy-Reeder and Wallace Whitney. Detroit: Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit, 2019. 56 pp.

Michel Parmentier does not like to be treated as important

He needs to think he is forgotten33Michel Parmentier, in Michel Parmentier: December 1965 – November 20 1999: A Retrospective, ed. Guy Massaux (New York: Ortuzar Projects and Paris: …

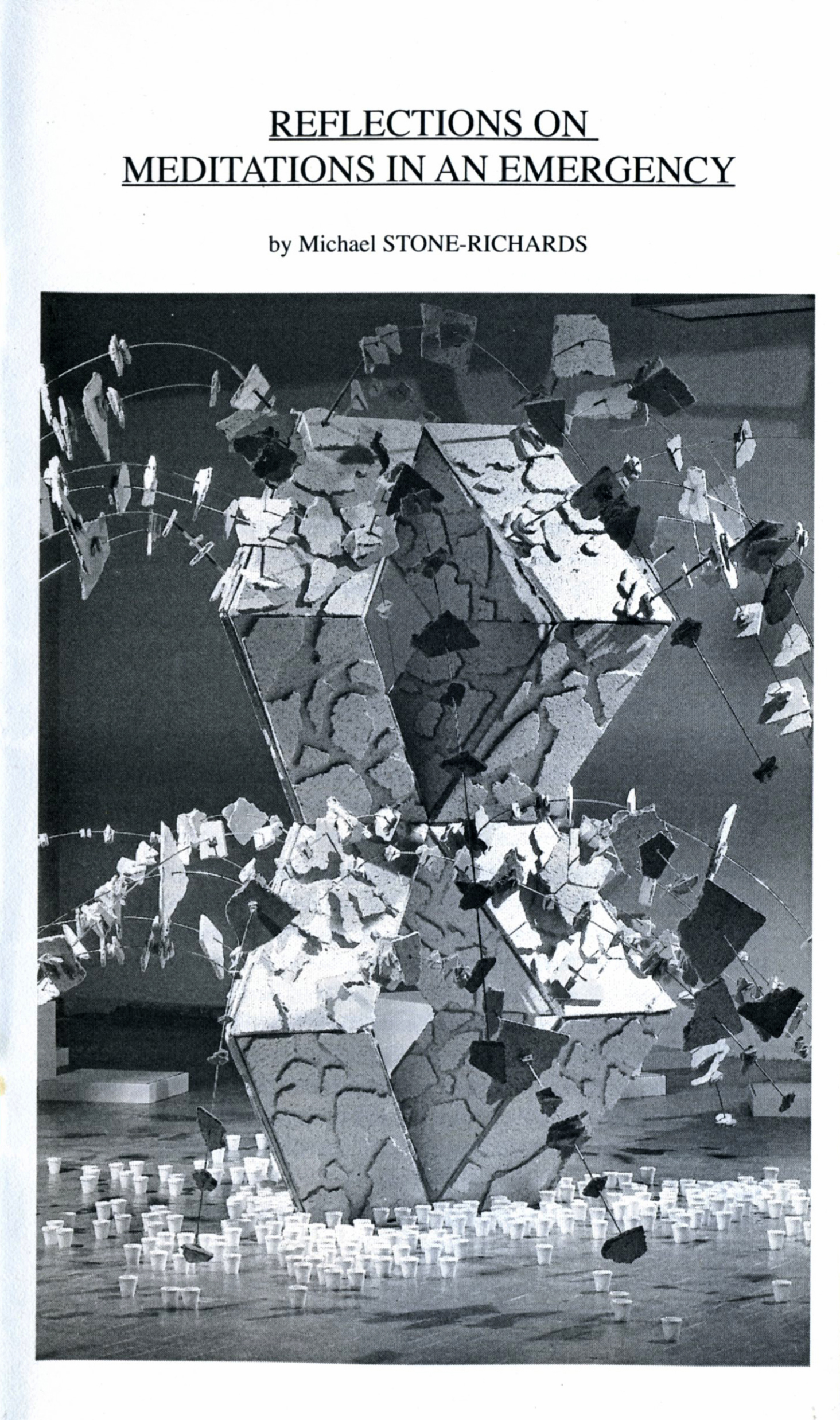

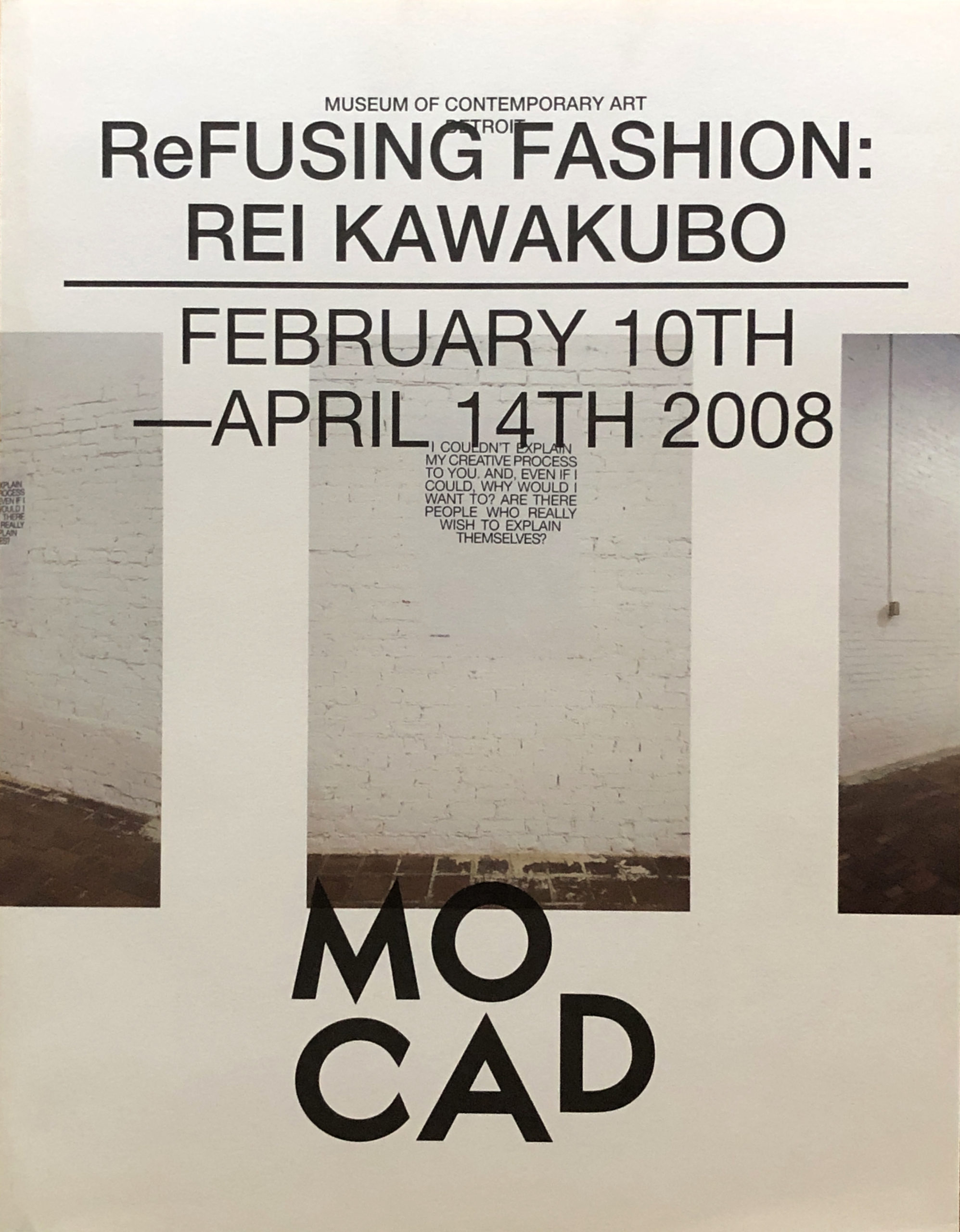

Since my arrival in Detroit there have been many surprises which have delighted me – filled with light - and enriched my life; indeed, one of the rewards of travel and being new to a place is being open to it in a way that any native-born person can scarcely be. Witnessing New Music Detroit’s performance of Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians in the second year of MOCAD’s existence - 2007 - remains one of the great and moving experiences of my life. That performance was the moment I felt both that MOCAD would succeed as a site of contemporary art and thought but also it was the moment, too, and that to my surprise, when I realized that I may have found a place to live and to live with intention. (When I think of this great performance, I also think of MOCAD’s inaugural exhibition, Meditations in an Emergency (2006) and conjure up an image of Nari Ward’s extraordinary White Flight Tea Bar made onsite with material from the ceiling of MOCAD’s past history as a car sales room, the image of which graced the cover of the printed version of my lecture – MOCAD’s inaugural lecture – reflecting on the exhibition (October 2006).)

MOCAD’s Comme des garçons exhibition of 2008 was another such moment, as also MOCAD bringing in, along with major exhibitions, Sanford Biggers, Leni Sinclair, Arthur Jafa, Danielle Dean, Tyree Guyton (whose painting, beyond the Heidelberg Project, utterly surprised me in its delicacy of touch, something wholly unsuspected by me), Peter Williams (about whom the novelist and critic Lynn Crawford had never stopped speaking since my arrival in town), and Conrad Egyir, but also the entrancing video art of Anne Lislegaard: 2062 (which remains to this day one of the most beautiful installations that I have experienced), along with such group shows that have marked me and many others: The Architectural Imagination, fresh from the Venice Biennale – how one wishes that MOCAD had done more in the realm of architecture exhibitions! – Crossing Night: Regional Identities X Global Context; Sonic Rebellions on the sound of ’67 (which aided me in my thinking about sounding as practice, as well as being one of the rare exhibitions on Detroit ’67 which brought new insights to bear); the extraordinary post-Symboliste, para-modernist For the blind man in the dark room looking for the black cat that isn’t there!, and last, but not least, the precious Black is, Black ain’t which came from the Renaissance Society in Chicago and the catalogue of which is by my hand as I write this. What an education! One of my early mentors, the philosopher Michael Tanner, used to insist to his students: Philosophers of art - I began my post-graduate life in philosophy of art - have to stay abreast of contemporary art or their work will become both dry and irrelevant. In my early preciosity, I would travel allover to follow developments in dance, music, performance, and poetry in the mode of Prynne and Fourcade, but when I taught Modern Art History would essentially stop with the IS, Beuys, and post-Négritude. Bref, Detroit is where I learned to be with the contemporaneity of art practices. My version of John Cage’s How to get started (1989), which I performed at MOCAD in 2016 at the invitation of the Slought Foundation and the John Cage Trust, was my attempt to register this set of identifications and changes in sensibility as a surprise to oneself.

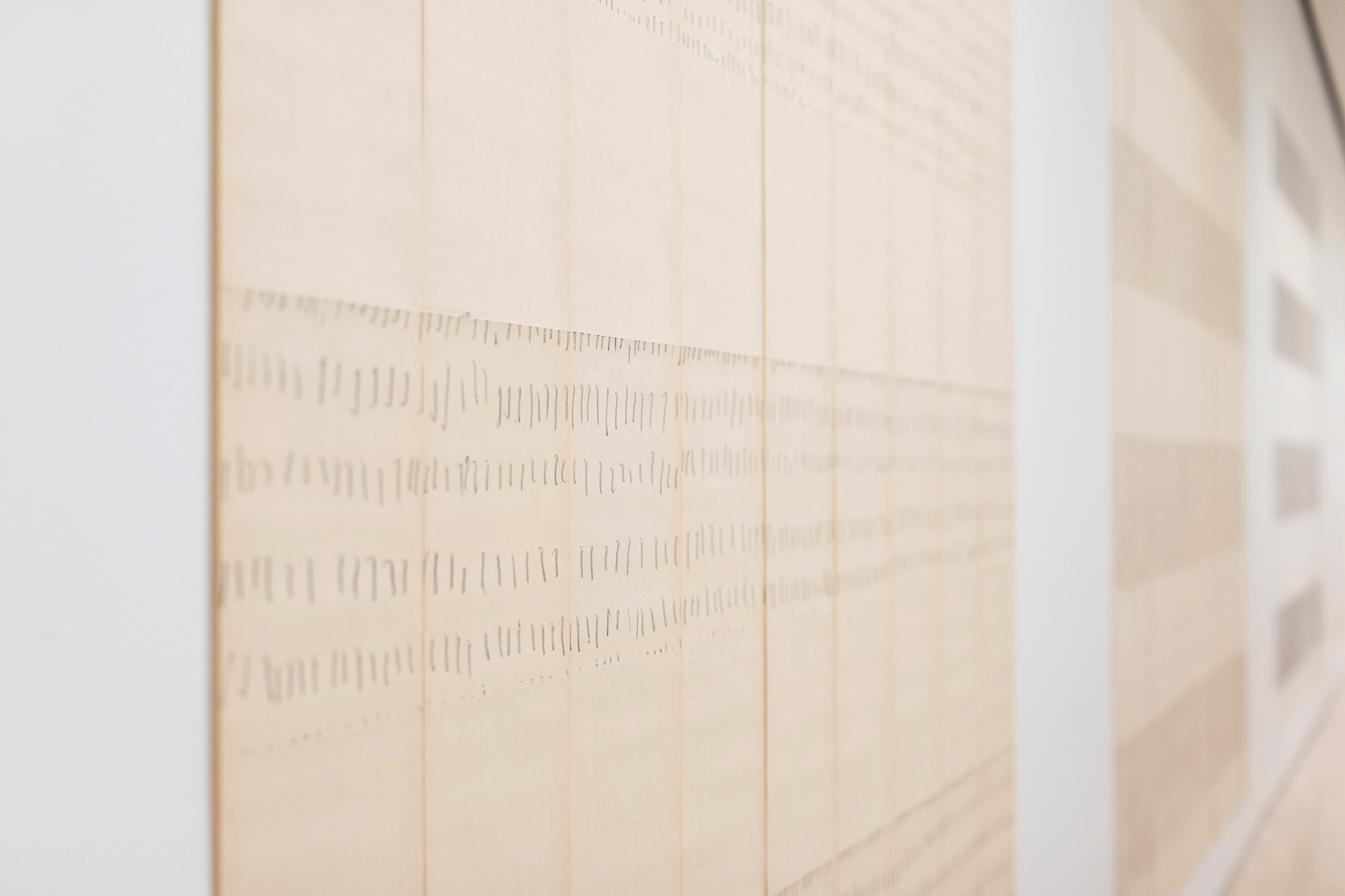

Michel Parmentier, installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2018.

Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

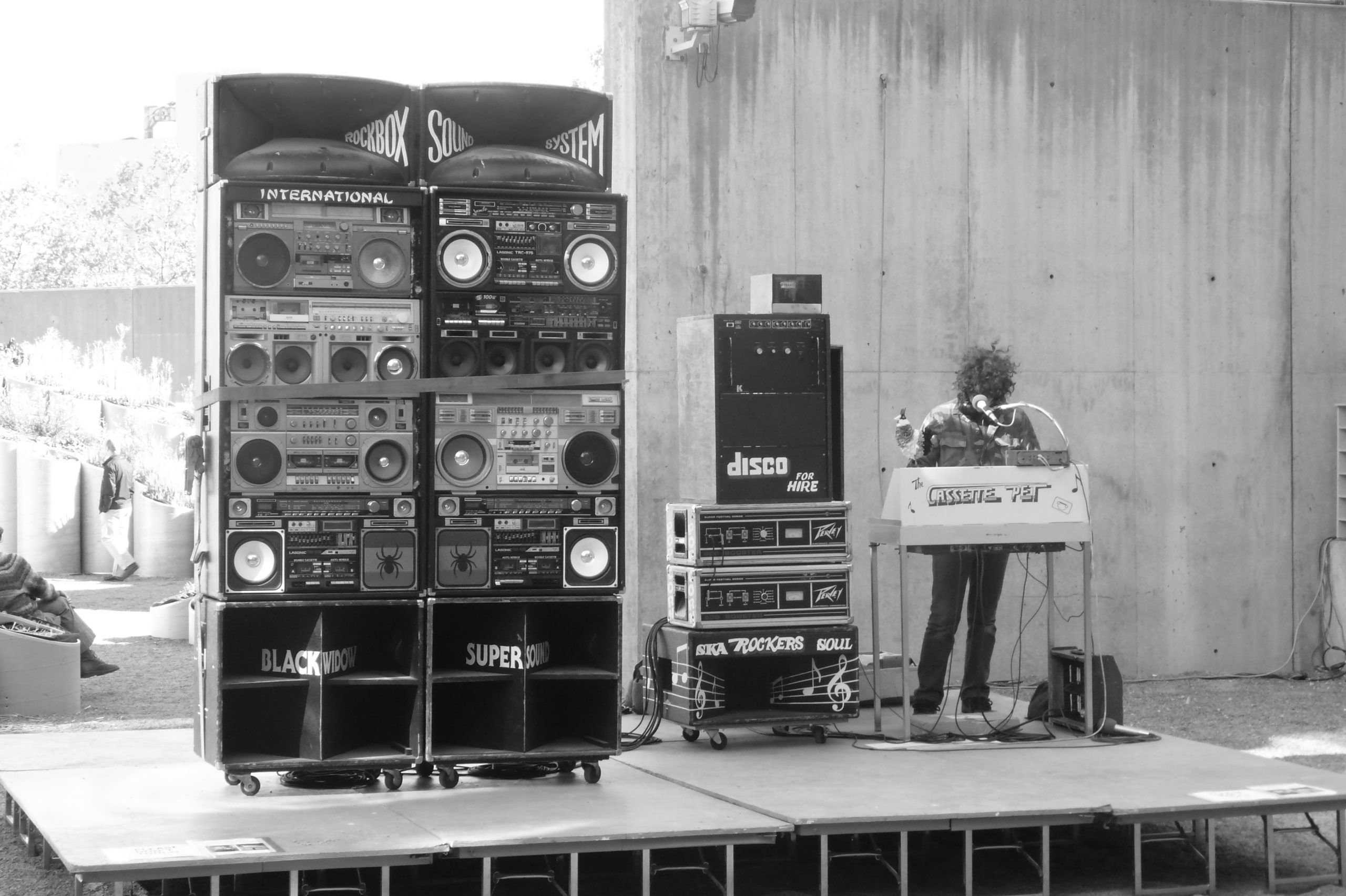

Before I leave the subject of the experience of surprise, I feel the need to touch on another instance of surprise and follow it through as an example of the role of identifications which I am beginning to realize is more and more one of the distinguishing features of contemporary Art Writing, in this case in the realm of music, and here I think of Chris Fachini’s sound system and dub music, also in Meditations in an Emergency, which also took me utterly by surprise and left me asking, What is going on here, with art boys and dub music, a music from a very particular part of my childhood in England, aspects of which still mean much to me, but which, in a real sense, I had long left behind? Let me explain.

In the Summer of 2006 as I was leaving Brooklyn for my new position – and life – at CCS in Detroit, I attended the Whitney Biennial. It was not a show that was particularly memorable, but I recall – without remembering the name of the artist – listening to some music that skirted around what it wanted to be before it became clear that it was…dub.. deep bass music designed for sound systems from the Jamaican club scene, with a form of vocalization best described as sprechstimme for the reggae voice, heightened speech, very rarely song, though like hip-hop there was often a professional (female) voice in the background. Dub always came with a musical (no song) VERSION for live perfomance in the dance hall for vocal performers – shouted – and was designed to be heard through a custom-made sound-system (the artisanal aspect of popular culture). Slow bass to rock you, but a voice to shock you. Here I was in The Whitney and out of nowhere I was hearing this music of the club scene of (a part of) my youth in what was clearly an art version, read meta, and so inevitably a lighter version. (Under heavy manners was one of the expressions used by dub performers to indicate the heaviness of dub, meaning, You – my competitor – will be disciplined; You will submit. A term of etiquette. A term of conduct – but what is performance theory if not etiquette in construction or being made visible?) I happened to be hanging with people who knew the artist but he had nothing of any interest to say and so I just left it behind and got ready to move to Detroit. Fast forward to the opening exhibition of MOCAD (with which I got involved the moment I arrived) in October 2006, and Klaus Kertess, the inaugural curator – I will deliver the inaugural lecture – has curated a certain Chris Fachini with a sound system into the show. I know what a sound system looks like and here is one in Midtown Detroit, playing dub. Granted we cannot be abreast of everything new, but I was genuinely taken aback at this trend, as I wanted to think of it, this sound culture. To be sure, dub music had long crossed the threshold from Black West Indian subculture into parts of student culture and the post-punk 1970s, i.e., the sound of dub had become one of the available sounds for cultural expression of difference and assertion, in the same way in which my daughters, without my knowing it, will as very young teenagers, start listening to Rage against the Machine and other sound performers, specifically sound performers, such as System of a Down. (One summer they sat me down in front of YouTube and introduced me to their sound culture and it was all noise based!) That’s how culture works – it ends up on the BBC or PBS…eventually, and the smart ones move on. But there was something else going on here, which I came to think of as not only very meta but also like a shadow of Alan Lomax, namely, the ethnographic collection of music as the means for listening not only to music away from the mainstream but a culture, a sound culture. There is something about hearing, and (structured or attentive) listening, that allows for the possibility of more available and thus receptive modes of sharing – we will rock you takes on new connotations – and the art frame, distinctive to Western modes of art, has become one of the principal ways of coming out of our skin and entering into the frequencies of otherness. The sound cultures of reggae and (parts of) dub most recently entered the mainstream through Steve McQueen’s Small Axe38Small axe, but hear also, small acts, that is, the everyday. anthology collection (BBC and Amazon, 2020), and here in Detroit, in 2021 Red Bull showed Akeem Smith’s No Gyal Can Test, a multi-media installation – video, photography, sound, sculpture – the mainstay of which was the music, dance, and vernacular photography of Jamaican women displaying their pleasure through homemade fashion in the context of dancehall culture.39In May of 2021, I held a conversation with Akeem Smith about his solo exhibition at Red Bull Arts, Detroit. See, “Archiving the Black Diaspora: … Stunning. It conveys a world of intense woman on woman pleasure and sociality at once ethnographic and evanescent for which the frame of art becomes a moment of possible capture for limited transmission. Watching Smith’s video installations is as visceral as it gets in contemporary practice – only Steve McQueen’s films have left me more put out! And the reversible porosity of this process – from subculture to mainstream, black to white, and vice versa - can be grasped currently with Sonia Boyce’s social practice performances in Radio Ballads at the Serpentine Gallery where Boyce and collaborators have taken the music and social commentary of the English folk music revival - as embodied principally in the work, the music, and experimental radio documentaries of Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, Charles Parker and collaborators between 1958 and 1964 (BBC Radio) - as base for an exploration of practices of Care.40See the rich documentation for Radio Ballads on the website of the Serpentine Gallery: https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/radio-ballads/ … (It will always be the BBC which simply has the largest archives of music and documentary culture. Ask John Akomfrah.) Since there can be no doubt about the various sounds of pain or distress, Boyce inquires of the sound(s) of Care, and at certain points she frankly equates Care with Love.41Cf. Sonia Boyce, Like Love (Berlin: The Green Box, 2010).– It’s possible to see Sonia Boyce and Theaster Gates as two Black international artists based on either side of the (Black) Atlantic whose forms of Social Practice find articulation in vocalization through engagement with folk music: be it the blues, gospel, Black church music for Gates – Gates’ work with the Black Monks of Mississippi from 12 Ballads for a Huguenot House (Documenta 13) to the experimental vocalization of the Black Monks in The Black Monastic (Serralves Foundation, Porto, Portugal, 2014) is a key development here – or, for Boyce, the English folk music tradition as recovered by MacColl, Seeger, and others; however, what is most poignant is that though both root themselves at moments in the particularities of folk tradition each determinedly transcends the folk form as they enter into practices of hybrid vocalization drawing on Japanese monastic traditions of incantation (Gates) or Dada (Boyce): this is Boyce’s latest stage in the experimental vocal improvisations in Feeling her Way, her contribution for the British Pavilion of the Venice Biennale (2022).42Cf. Emma Ridgway and Courtney J. Martin, Sonia Boyce: Feeling Her Way (London: British Council and Yale University Press, 2022). On Social Practice / … This same Sonia Boyce – rightly having a moment at the Venice Biennale – also, like Steve McQueen, had a developed take on the genre of Lovers Rock,43Cf. Mark Crinson, “Telling Lyrics,” Annotations 2 (1998): 24-27. so there is a genealogy – a series of affective identifications - running through certain artists like Gates, McQueen, and Boyce from the folk or cultural dancehall forms to experimental vocalization as a high point of fundamentally social practice forms defined by Care.

Francesca Berardi. Detour in Detroit. Milano: Humboldt Books, 2015. 280 pp.

A few years ago, when I first read this book and met its author, I was comfortable in saying to all who would listen to me, This is the best book on Detroit in recent years! If irritation resulted, so be it, all the better if it led to the book being read. Detroit was fortunate to have such a friend, such a witness. A young Italian journalist on a fellowship in New York by chance visits Detroit and is taken by surprise, which is to say, not prepared for what she encounters. She decides to return to the city on her own in her own time knowing no one – this is the detour – on six occasions, using Airbnb. After a while people she meets begin to connect her with others with whom she might stay on her visits. This chance element makes her writing the record of a form of dérive of both city and interiors (of homes as well as people with whom she stays or comes to know). This openness, and its related receptivity is the mark of Francesca Berardi’s writing, but what it leads to is also telling, since she also reports on her experience of dwelling with others: she does something that is so very, indeed, exceptionally rare in writing about Detroit: she writes about domesticity and the spaces and acts of domesticity. Weaved as such accounts are into her experience of the arts scene - especially the post-studio practices for which Detroit has become rightly known in the past fifteen years or so - along with the most compelling account of the urban gardening scene (and not the usual suspects),44On the Black presence in urban gardening, cf. Berardi, “A Passion for Basil can change your Life (And if nothing else, there’s wild Garlic),” … and making visible the relations between certain modes of Black being in the city and White people and their institutions - in its heyday Amy Kaherl’s Detroit Soup was the only place for an organic meeting between the arts scene and Black working class people - Berardi uncovers new subjects of Detroit and allows for a new vision of hospitality, domesticity, and social / spatial practices to enter visibility and find orientation in the new mental map of Detroit in the act of emerging from the compulsive scenes of ruination.45See, for example, the chapters set in interiors and which set out on the quest for ideas from the habitants of such interiors, for example, Grace Lee … Here you will find accounts of an old-world Italian restaurant that does not exist in the Old World (“The Old Days, between Veal Scaloppine à la Tosca and Madonna’s Fingers,” 67-79). It is a work of great generosity of spirit. When placed in the context of the first great conceptual work on Detroit and the Heidelberg Project carried out by the architecture discourse formulated by Kyong Park (upon leaving Storefront for Architecture in New York) along with the School of Architecture at Columbia University (Richard Plunz), the School of Architecture at University of Detroit-Mercy (Stephen Vogel), and Architecture at Cranbrook (Dan Hoffman), Francesca Berardi’s Detour in Detroit offers a new and generous language for thinking Detroit.

We chase the sound / …/ Invented stories / With silent tracings

ADULT. and Shannon Funchess, Detroit House Guests

ADULT. / Nicola Kuperus and Adam Lee Miller. Here I can write, Our Avant-Garde, or at least, I want to, but I still have not arrived at a satisfactory formulation of what I would mean by this. The phrase came to me spontaneously after seeing them do a performance (with a vacuum cleaner) first at MOCAD and then in a space in the Russell Industrial Complex, and noticing an audience deeply attentive and co-creative. Addie and I became friends with two sets of people in Detroit in no small part because the question of domesticity was essential to their practice, by which I mean not only their various acts of making but also as an intentional practice of living, the practice not of making or producing stuff, but the Aristotelian praxis of transformation of the self through reflexive action that allows for shared world-views. We recall one friend saying, Have you noticed how no one talks about domesticity when discussing Cass Corridor artists? (They were too busy trying to be heroic.) And we responded, Or in any other facet of Detroit art – and this in spite of how urgent and complex the question of domesticity had become in critical theory, feminist and other wise. Just think Beatriz Colomina’s Domesticity at War (2017)! Across their intermedial practice – in music, photography, film, painting, performance – it is strangely powerful and not a little disorienting when one realizes that they are constantly turning around this question of domesticity: of home, of how to live, of how to be alive, of how the domus and its attendant ideology imputes camouflage, and with it, loss of agency, even as intentionality and attention is put into the curating of interiors for living. – Theirs is a space for dreaming. - Domesticity is protection, projection, Care, but also bathos. Domesticity is immanent temporality, not ecstatic temporality, as base for possible release and return to ground. (The films, the horror films by Nicola and Adam, are nothing if not an all-out assault on domesticity. This is part of their dialectic.) Domesticity is both the making and un-doing of woman and femininity. An ethnomethodological dramaturgy. I see these issues and questions in the way in which after this national tour or that European tour or that British tour (since the Brits are no longer Europeans) they always return to Detroit, which is also to say, to their space of intimacy, the place of retreat and welcome to friends – the Detroit House Guests of 2017! This project in domesticity and hospitality when artists were invited to live, perform, and record with ADULT. in their Detroit home, without necessarily being friends ahead of time – Dorit Chrysler, Shannon Funchess, Michael Gira [see DR3], Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe, Douglas J. McCarthy, Lun*na Menoh [see DR3]. I regret that I cannot reproduce the black and white photographs that accompany the album, an almost ethnographic set of photographs of cooking, shopping for food, moments of play and relaxation, a couple of loo roles, a warm unmade bed, people without makeup, and photographs of performances in the house (not in the studio), as well as photographs of making and changing of linen! – And yet how the color photographs of the album cover make the humble quilt suddenly mysterious in that surréaliste manner of staging that Nicola perhaps inherited from her fascination with Guy Bourdin - another source of our friendship and my admiration. 24 years. In Detroit. Nicola Kuperus and Adam Lee Miller. Intermedia artists of international renown, unique in the Detroit landscape, generous in their talents with others: again, music, film, plastic arts, performance art, photography as a unified but challenging practice - on stage, in the city, in airplane hangars, in industrial settings, in colleges (Rhode College, CCS, and others), in galleries, in museums, but also in their home. Over 24 years they have been a key measure of avant-garde collaboration and fearless innovation both in Detroit, nationally, and internationally. Their concept work Detroit House Guests was a landmark in art / music collaboration and the practice of hospitality, a subject, like domesticity, almost untouched by most artists in Detroit. Our avant-garde, meaning, provisionally: something distinctive to us, something emergent from here, implicating the question of place, and yet, at the same time, if an avant-garde cannot be reducible to place, place, then, as the point of departure. Place, too, as the occasion of being, the means of flourishing. Detroit. 24 years of it - even more, if you include the College Years at CCS – 24 years of intentional being, of the practice of becoming who we are – who we might yet be – in acts of fierce invention. And when Nicola performs with not one but two microphones? The noise / sound barrier is broken, shattered. Definitively. The sound-world they create a new kind of hospitality. There is nothing like them! They exemplify the politics of staying so central to contemporary practice where the reflexive practice of Care has become necessary at the communal level, but where love becomes indistinguishable from friendship in the moments of intimacy in which we all long to be. What if, then, our avant-garde is a figure of the outline of a new kind of friendship?

Another world / Another life.

ADULT. and Douglas J. McCarthy

References