Drawing Detroit

(Iteration #2)

Curated by Jennifer Junkermeier and Ryan Harte

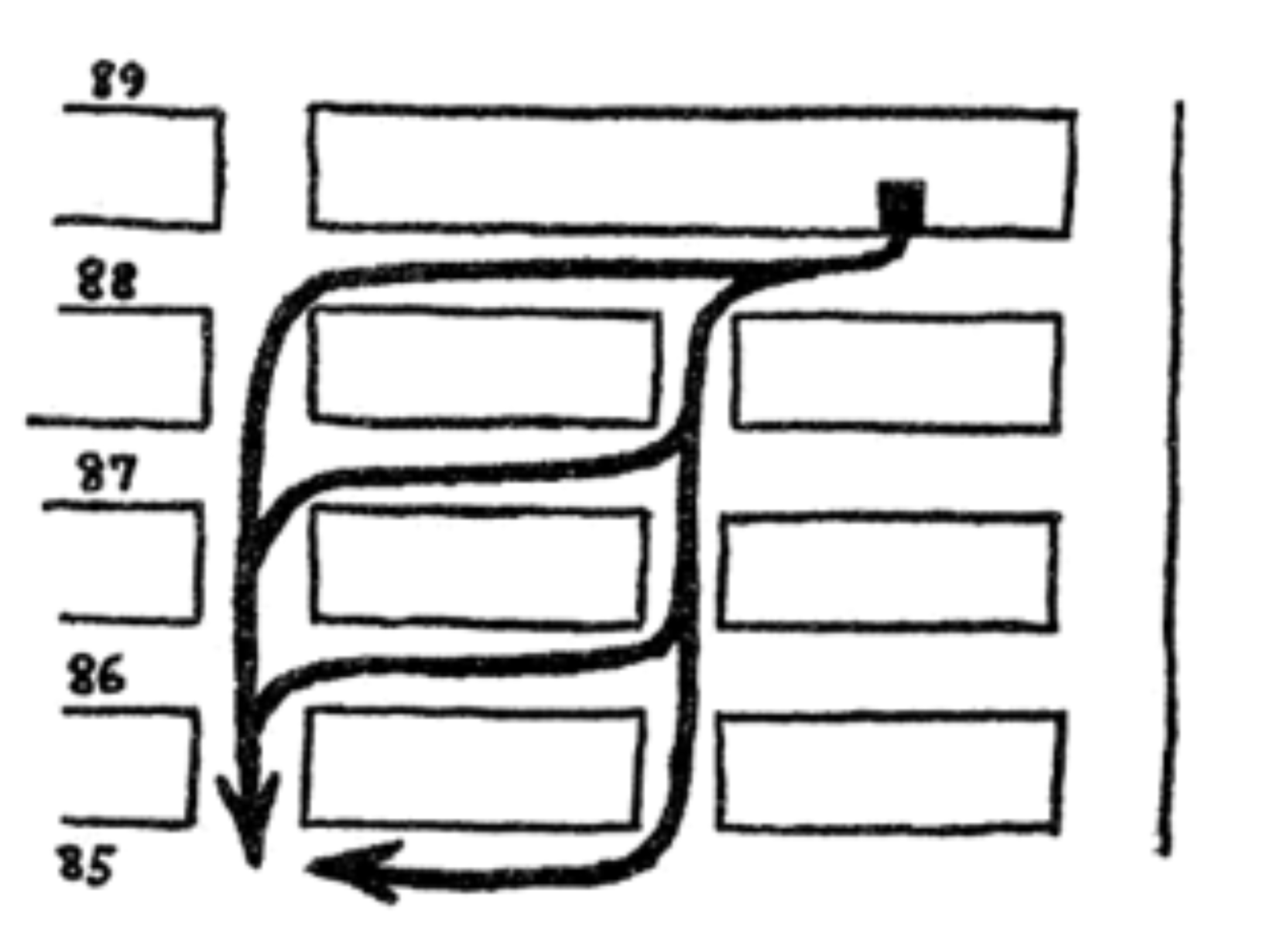

Illustration from Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961,

Vintage Books p. 181 depicting multiple routes to a destination.

People move around a city using a variety of vehicles and modes of transportation: car, bus, bike and foot; freeways, surface streets, bike lanes and sidewalks. Moreover, besides the chosen mode of transportation is the choice in pathway, based on any number of factors. Moving from point A to B presents innumerable possibilities on how to travel between spaces, providing a diversity of cities, each lying within the same city, from street to street, thoroughfare to thoroughfare. In an analysis of navigating a neighborhood, Jane Jacobs describes the multiplicity of routes available to reach a destination, especially along short blocks (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961, Vintage Books). For Jacobs, the variety of routes is important to activate all parts of the neighborhood, bringing liveliness, diversity, the safety of “eyes on the street” among other benefits. As individuals inhabit and navigate a unique experience of our shared city, one’s chosen route can bring insight into how one feels about a city and how one understands a city.

To better explore and share the varying ways different individuals experience the same city, for this iteration of Drawing Detroit for Detroit Research we developed a set of prompts (questions and scenarios) with the goal of finding a way for people to provide personal insight into the way they experience Detroit. We invited a group of people to respond in the form of a hand-drawn map with an emphasis on experimental articulation. We asked participants the following: When creating your map, we’d like you to share your unique “insider” knowledge of how you understand and navigate your neighborhood. Particularly, what information can be conveyed in a hand-drawn map that GPS navigation won’t reveal? The choice in path is of particular interest because it is a subtle reflection of one’s view of a city as well as the structural impact of the city on an individual. These routing decisions are sometimes conscious, sometimes unconscious: influenced by convenience, perceived threats, routine, as well as other factors. Moreover, hand-drawn maps provide an opportunity above an atlas or contemporary GPS navigation in that they can reveal intimate knowledge of a neighborhood.

Consider the following questions when thinking about hand-drawn maps: What are the local landmarks in your neighborhood? What shortcuts do you take to get home from work? Where or what route do you walk your dog? If you ride a bike around town, which streets are bike friendly? Or, what is the most bike friendly route to work for you? Where do you always look for parking in specific neighborhoods? What is your scenic route home from work? What route do you take for experiencing your perfect day in the city of Detroit? Where do you walk? Where do you jog? What is the route to your favorite restaurant from your home? What do you encounter on your way that always makes you smile or makes you angry?

A rich understanding of Detroit is the amalgamation of individual insights of the city. As our individual paths are “mixed and mingled with one another” (Jacobs, Great American Cities, 180), to truly understand a city would necessitate knowing each of its constituencies; to know and understand our neighbors.

When we first started to think what these maps may reveal we thought it would be about specific roads and physical movement. To our surprise, what we found was that within the “maps” were histories, feelings, experiences and representations of Detroit that could and should warrant further investigation. Equally interesting in the “maps” people created were how reflective they were of their own existence, their own personalities. The project had/has no goal of unearthing any grand conclusion. Instead the maps are documents; archiving a time, place and existence within it. Apart from revealing intimate knowledge of a neighborhood, these maps are a guide and invitation to experience another person’s understanding of a shared city. These maps are a launching point to new conversations with buildings, trees, shops, people, and ways of life.

For example, M. Saffell Gardner’s map depicts a timeline of his studio spaces, past and present, throughout the city. Some of the spaces no longer exist, lost when the buildings were torn down. The second graders from Mrs. Turner’s class drew idyllic maps full of high-rise buildings. Alex Hill depicts a Detroit of bubble neighborhoods, the Arts Center, Cass Corridor, and Livernois Ave. separated by vast, still untraveled expanses. Such a variety of ways to inhabit the same space reflects the rich diversity in heritage, age, and personality of the people of Detroit.

Technological power and smartphone ubiquity has brought GPS navigation to cars, bikes and public transportation—delivering the quickest or shortest route. As reliance upon hand-drawn maps or simple written directions wanes, the document of the map serves an important auxiliary function in telling a great deal about the how we exist in the city at that time, reflecting thoughts and behaviors. Partly a time capsule, maps have a special quality in their ability to imbed knowledge of a place and a time.

As a practical object, missing a turn with a simple hand-drawn map could easily leave the traveler lost. GPS alleviates the inconvenience of unexpected construction detours or re-routing after a missed turn. As the technology is designed to provide the quickest or shortest route, it does not know how to show the “scenic route.” By contrast, directions delivered by hand were often simplified to involve less turns. Hand-directions account for convenience, can incorporate useful shortcuts or explaining tricky turns. GPS at once reduces inconvenience but also routinely delivers the same routes to a destination. Obligingly following GPS navigation restricts serendipitous discovery of neighborhoods, even a street or two over. The next time you are on your way to a destination, leave early and consider a detour. Or, ask a friend for a map.

The people we invited to create “maps” for the project were members from our immediate community, friends and colleagues, made up of artists, writers and educators each with unique experiences and perspectives on Detroit. The following maps were created by ‘jide Aje, Halima Cassells, Clara DeGalan, Stephen Garrett Dewyer, M. Saffell Gardner, Alex B. Hill, and Mrs. Turner’s 2nd Grade Class from Nataki Talibah Schoolhouse of Detroit.

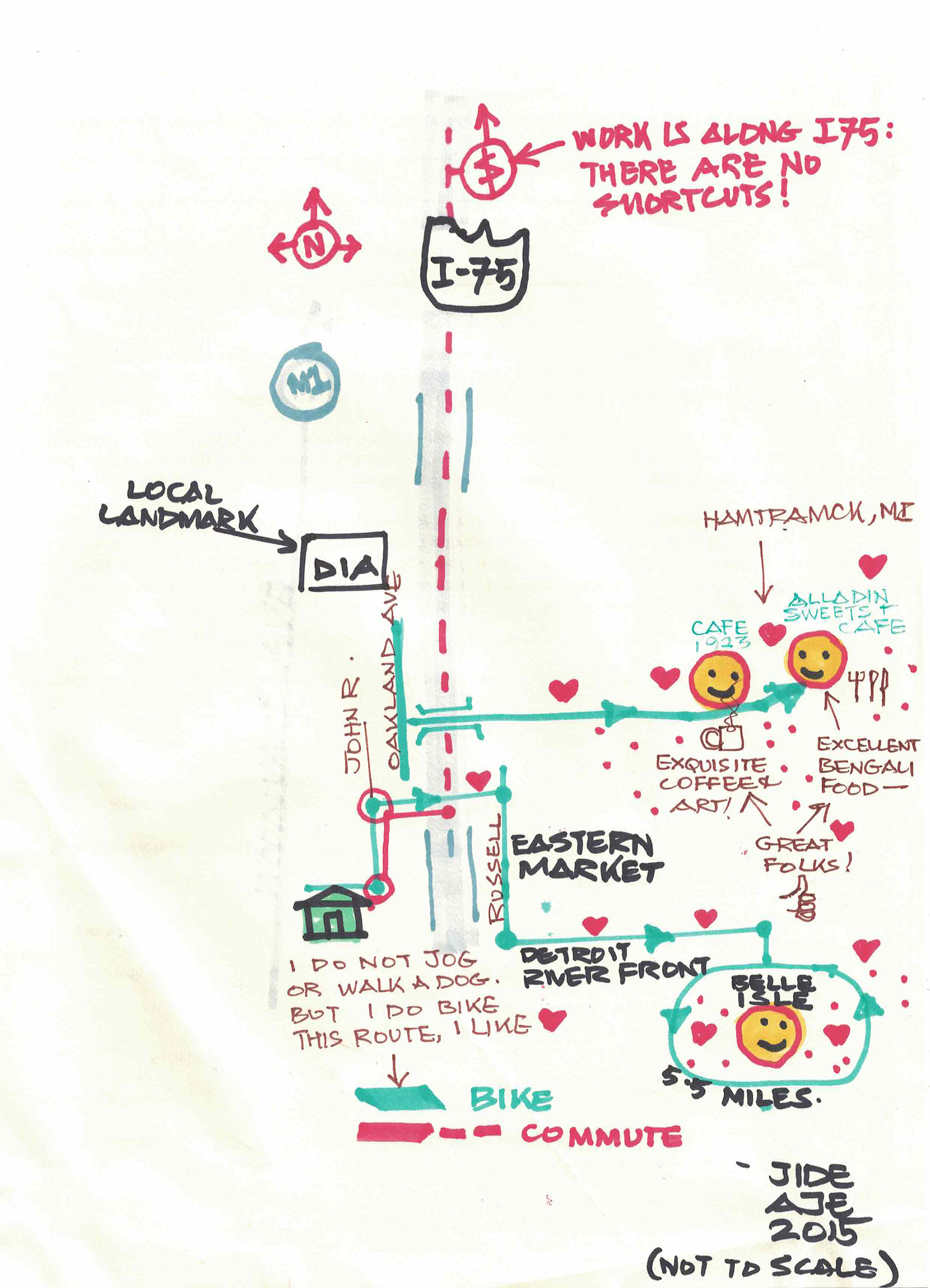

1. ‘jide Aje, Hand-drawn Map, Detroit, 2015

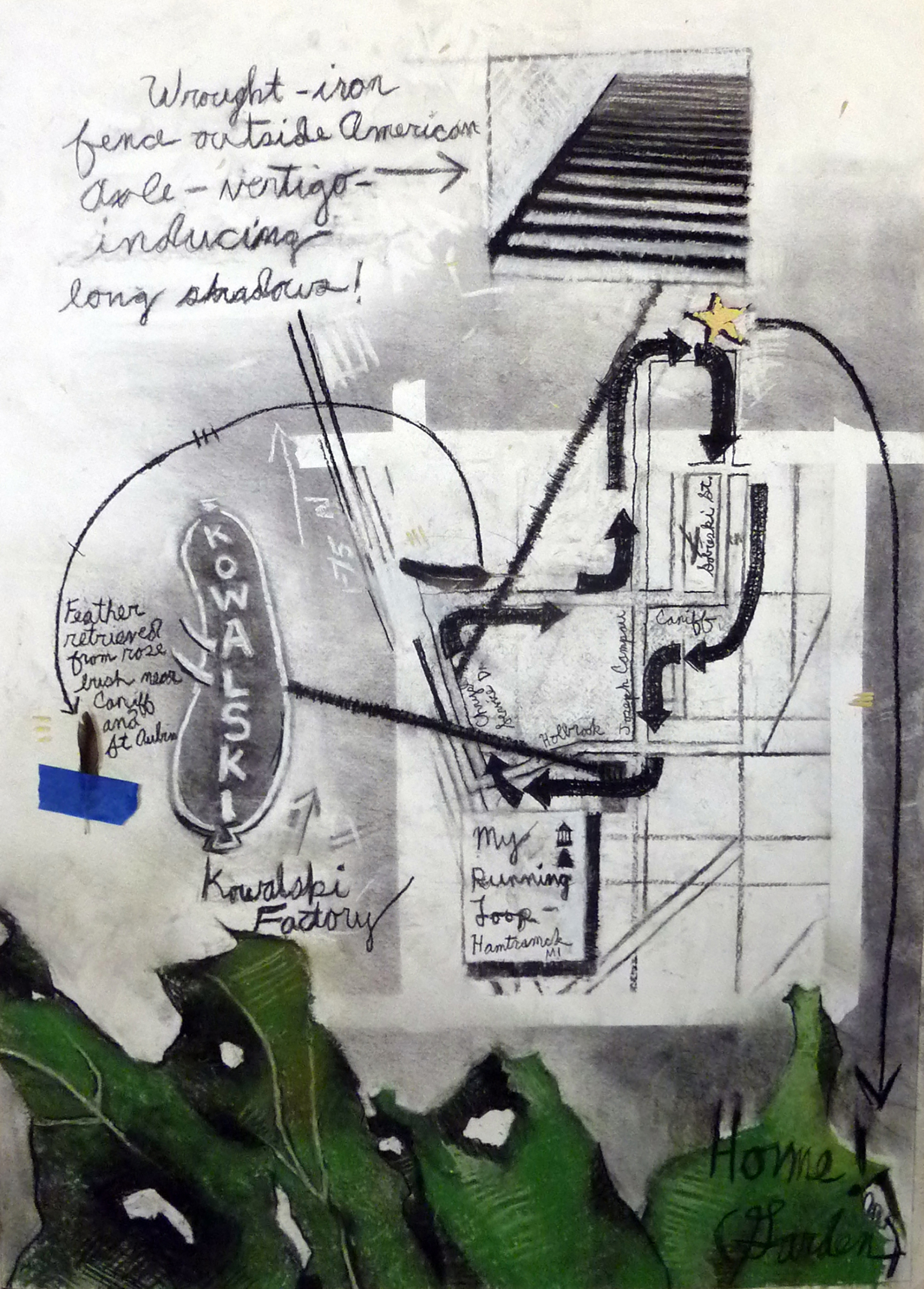

2. Halima Cassells, Hand-drawn Map, Detroit, 2015

3. Clara DeGalan, Hand-drawn Map, Detroit, 2015

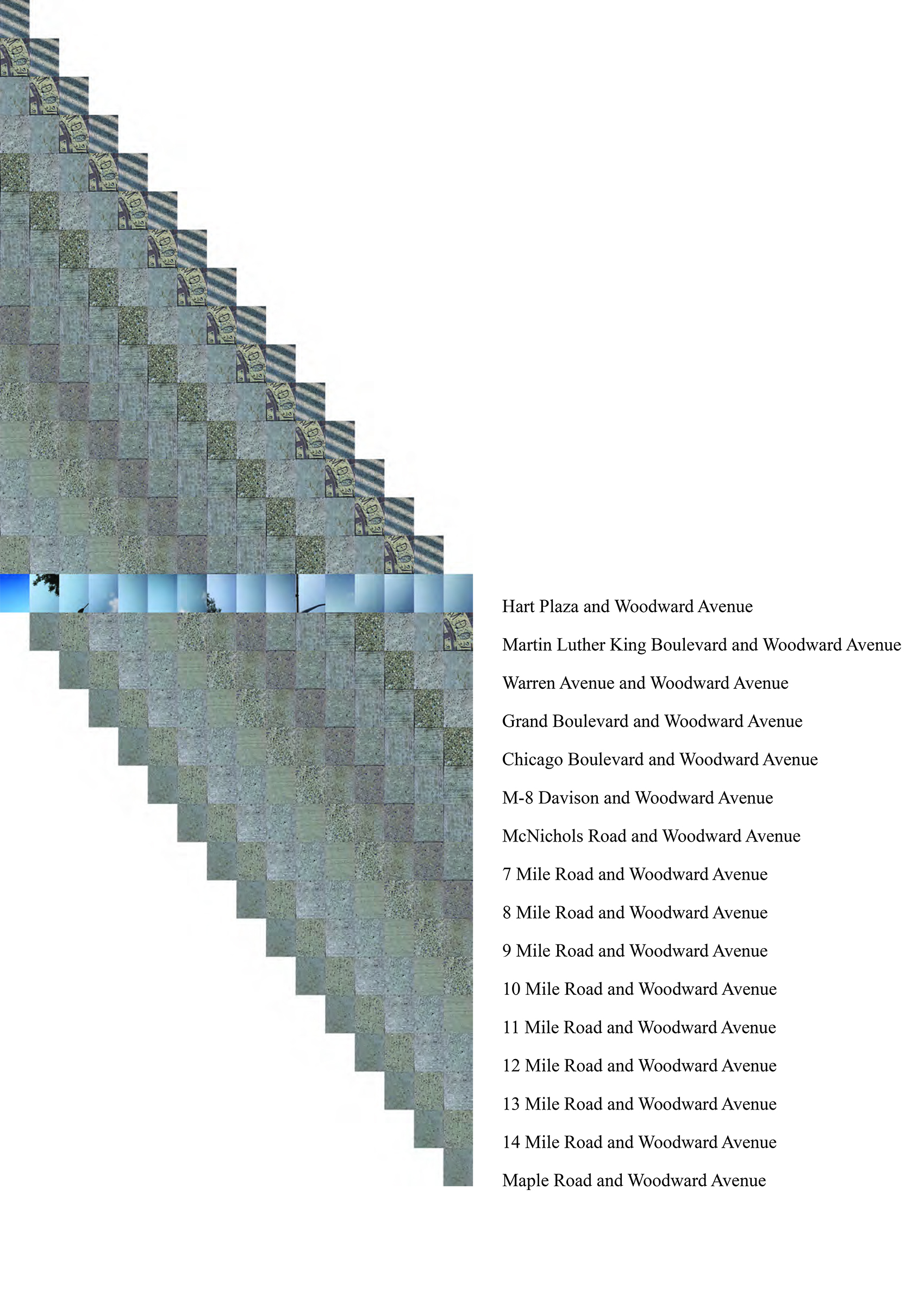

4. Stephen Garrett Dewyer, Hand-drawn Map, Detroit, 2015

5. M. Saffell Gardner, Hand-drawn Map, Detroit, 2015

6. Alex B. Hill, Hand-drawn Map, Detroit, 2015

7. Mrs. Turner’s 2nd Grade Class from Nataki Talibah Schoolhouse of Detroit, 9 Hand-drawn Maps, Detroit, 2015

‘jide Aje is a Detroit based artist who was born in Lagos, Nigeria. His main forte is painting. Aside from being an exhibited creator, he is an active member and supporter of numerous arts and cultural organizations and creative initiatives in Detroit.

Halima Cassells is a Detroit based artist/community advocate. She assumes leadership and outreach roles at O.N.E. Mile, Oakland Avenue Artists Coalition, Incite Focus Fab Lab, North End Soup, Center for Community Based Enterprise, Detroit Black Community Food Security Network and the Free Market of Detroit.

Clara DeGalan is an artist, writer and educator based in Detroit where she was born and raised. In addition to her studio and writing practice, she teaches at Wayne State University and Madonna University.

Stephen Garrett Dewyer is a Detroit based artist, writer and part-time professor. He is the co-founding editor of Infinite Mile: a journal of art + culture(s) in Detroit. He received an M.F.A. in sculpture from the Yale University School of Art in 2011 and a B.F.A. in Art History, Theory & Criticism in 2008 from the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA).

M. Saffell Gardner is a Detroit based artist, art historian, curator and educator. He holds B.F.A. and M.F.A. degrees in painting from Wayne State University and is a 2015 Kresge Fellow.

Alex B. Hill is a Project Coordinator and Community Health Worker who lives and works in Detroit. His projects and research focus on the need for greater community involvement in development and specifically highlights the intersections of power, privilege, and race in regards to health disparities, access to basic health care, and the social implications of medicine.

Mrs. Turner’s 2nd Grade Class from Nataki Talibah Schoolhouse of Detroit. Mrs. Turner (aka Alyson Jones) is an educator, writer, philosopher and founder of Searching for Telos: Philosophy for Children. She is a native of Detroit who in her spare time assists her family at Source Booksellers in its mission to make the Literary Arts Visible.