Blues & Roots: Fragments of a History

of the Detroit Artists Workshop1Blues & Roots refers to an album of the same name, recorded by Charles Mingus in 1959, released by Atlantic Records in 1960.

George Tysh

All photos by Leni Sinclair, courtesy of the artist

“No matter what becomes of it, art is local, local to a place and to a person, or group of persons… It happens somewhere, not everywhere.”

— Robert Creeley

“Why Bother?”2Robert Creeley, A Quick Graph: Collected Notes and Essays (San Francisco: Four Seasons Foundation, 1970), 40.

The Detroit Artists Workshop, an early instance of what’s now called social practice, didn’t come out of nowhere. In summer 1964, its young architects drew on ideas that were certainly in the mid-century air, but had been around much longer: from the Paris Commune of 1871 (the first workers government ever created), to the September 1936 formation in Detroit of UAW local 174 (the fledgling union that would soon take on the whole auto industry), to the 1957 birth in Europe of the Situationist International (a neo-Marxist group that emphasized the centrality of real-life activities endlessly experimenting and correcting themselves). While perhaps a few of us knew this history, all of us were keenly aware of the Civil Rights struggle, the Ban the Bomb protests, and the poetry-and-jazz phenomenon known as the Beat Generation. And the fact that poetry, jazz, and the other arts were terrifically intriguing in and of themselves was precisely the point.

By 1960, a watershed for the arts in America, modernist innovators Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Robert Rauschenberg had achieved critical acclaim and commercial success. Beat authors Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs, who had won legal battles against police censorship, were household names. And creative ferment began to spread across the country. In a sign of the times, proto-Pop iconoclast Rauschenberg collaborated with composer John Cage on works for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. And 1961 saw the release of Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation by the Ornette Coleman Double Quartet, followed in 1962 by John Coltrane’s Live at the Village Vanguard — recordings that shattered preconceptions about jazz as popular entertainment, unleashed a tide of experimentation, and stood as emblems of creative group dynamics.

DC5 (Detroit Contemporary 5), Danny Spencer, John Dana, Larry Nozero, Cherles Moore, and Ron English at The Artists Workshop 1965.

As if presciently, the summer 1963 issue of Kulchur — an avant-garde quarterly edited by poets LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Frank O’Hara, Charles Olson, Diane di Prima, et al — featured, among others: George Oppen’s The Mind’s Own Place (in which he exhorts poets “to listen, to hear evidence, to consider what indeed we have brought forth upon this continent.”); Louis Zukofsky’s A Statement for Poetry (wherein he writes of the “musical horizon of poetry” and the idea that “so-called pure music may be literary in a communicative sense”); and Larry Eigner’s Walls Dispose a City (his analysis of Gertrude Stein that affirms, “The milieu is carried by the language [style], which is always there…”).3Kulchur 10 (New York: Kulchur Press, Summer 1963). To my rapidly shrinking naiveté, such pieces foreshadowed a poetic revolution just outside the field of national awareness. What an incredible time to be a student and distracted by life!

As we look back on it, in fact, summer 1963 was the real turning point for students of the arts in Detroit. Many of us at Wayne State University were frustrated at the lack of connection between our classes and the political realities of the Civil Rights and anti-nuclear movements, and avant-garde developments that we could read about in Kulchur, The Jazz Review, Downbeat, Film Culture, The Village Voice, and a seminal anthology edited by Donald Allen, The New American Poetry, 1945-1960.

IMPRESSIONS

Our yearning for creative possibility hung over Second Avenue south of campus like a dense cloud. We almost seemed to be teenagers again, with nothing to do and nowhere to go. But one day photographer and film-maker Saul Columbus introduced me to Sheila and Carl Schurer, who had two little kids and more life experience than any of us, she a passionate literary scholar and he a painter immersed in abstract expressionism. Immediately we began an exciting conversation about art and community, until the idea for the Red Door Gallery came along as natural as you please. Carl knew Larry Weiner, a young painter whose father owned the car wash just south of Willis on Second, and soon we had another collaborator, as well as a funky storefront that the father let us rent cheap, right next to Larry’s own studio. After we cleaned and painted the space, made sure the toilet worked, and put out our sign, folks from the surrounding apartment buildings drifted in and started volunteering to keep the project open every afternoon, in shifts, and especially on weekends. The shows rotated every month, and we used the gallery for more than exhibitions.

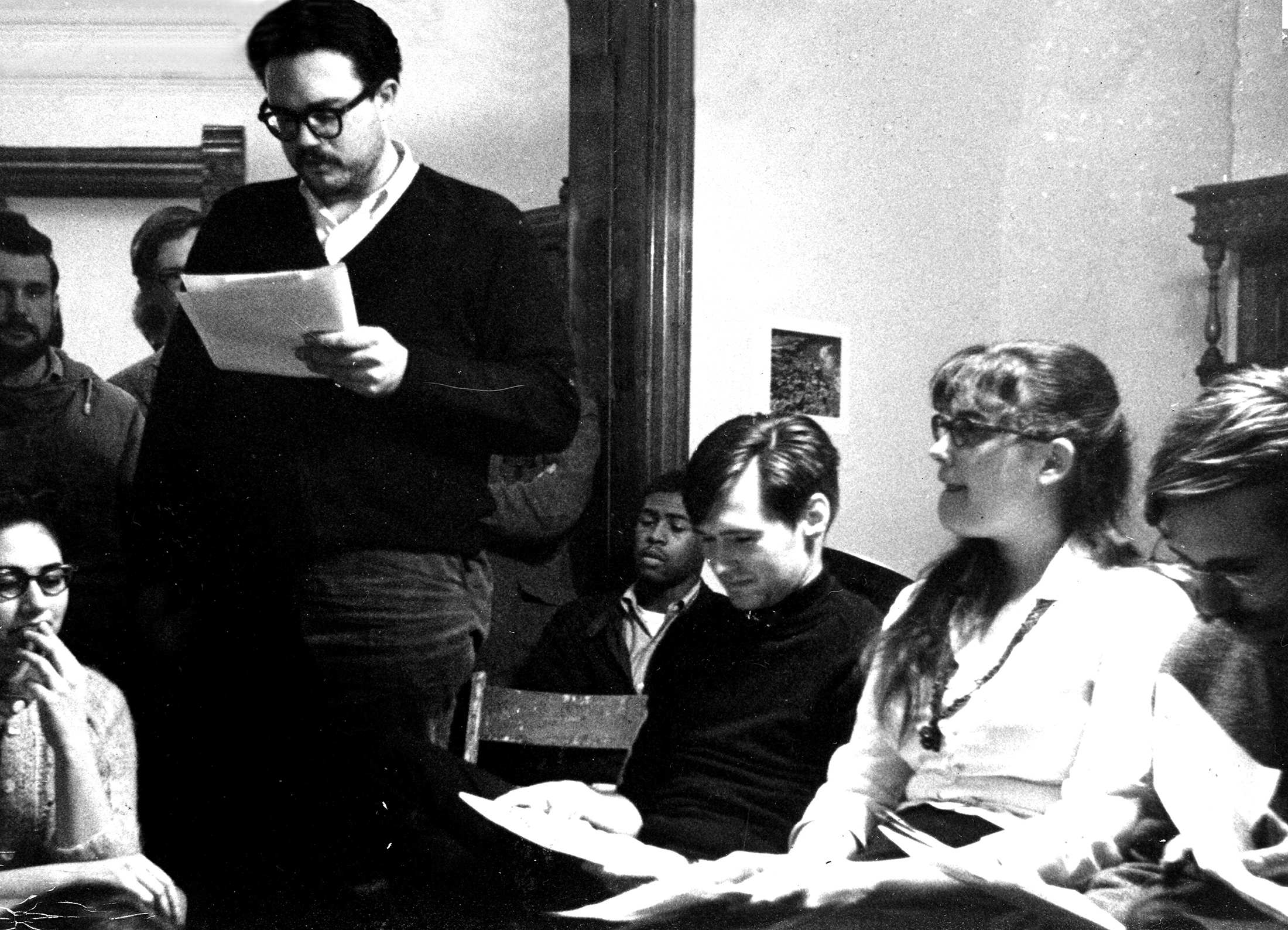

Artists Workshop reading, 1965.

L to R: John Sinclair, George Tysh, Gayle Pearl, Robin Eichele

Jazz trumpeter Charles Moore brought along a portable record player, and often practiced along with Coltrane’s 1963 Impulse release, Impressions — I’ll always remember the haunting sound of “India” as ‘Trane and Eric Dolphy described harmonic modillions in the air. Poet Robin Eichele dropped in to talk poetics, and sometimes gave a reading from his work, as well as lending a hand. There were evenings of New American cinema, one raided by the Detroit vice squad looking for (nonexistent) porn. And for one whole week, we hosted Ann Arbor’s experimental ONCE group (composers Robert Ashley and Gordon Mumma, painter Mary Ashley, and filmmaker George Manupelli, et al) who made the gallery the site of daily happenings. As we were preparing for this thrilling series, WSU professor-poet Keith Waldrop (instructor of a poetry class that read Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, and Gary Snyder, alongside the Donald Hall academics) dropped by with a guest: author Robert Creeley would read on campus that night and inaugurate our collective experience of the poetic sublime (followed later that semester by a Waldrop-organized reading by Robert Duncan, another mind-altering event).

The Red Door was truly DIY avant la lettre, as we took the means of production and distribution into our own hands. There were solo shows of painting by Carl, Larry, and Eizo Nishiura, as well as the ONCE events, a collage show, and even one of abstractions from Poland(!!) that Dr. Edmund Ordon, my Polish prof, helped arrange. But typically, the art critics from the Detroit News or Free Press stayed away, no matter how many press releases, flyers, and personal invitations we sent them. Thankfully, the gallery was at least documented by photographs that one of its founders, Leni Sinclair (then Magdalena Arndt), took near the beginning of her luminous career.

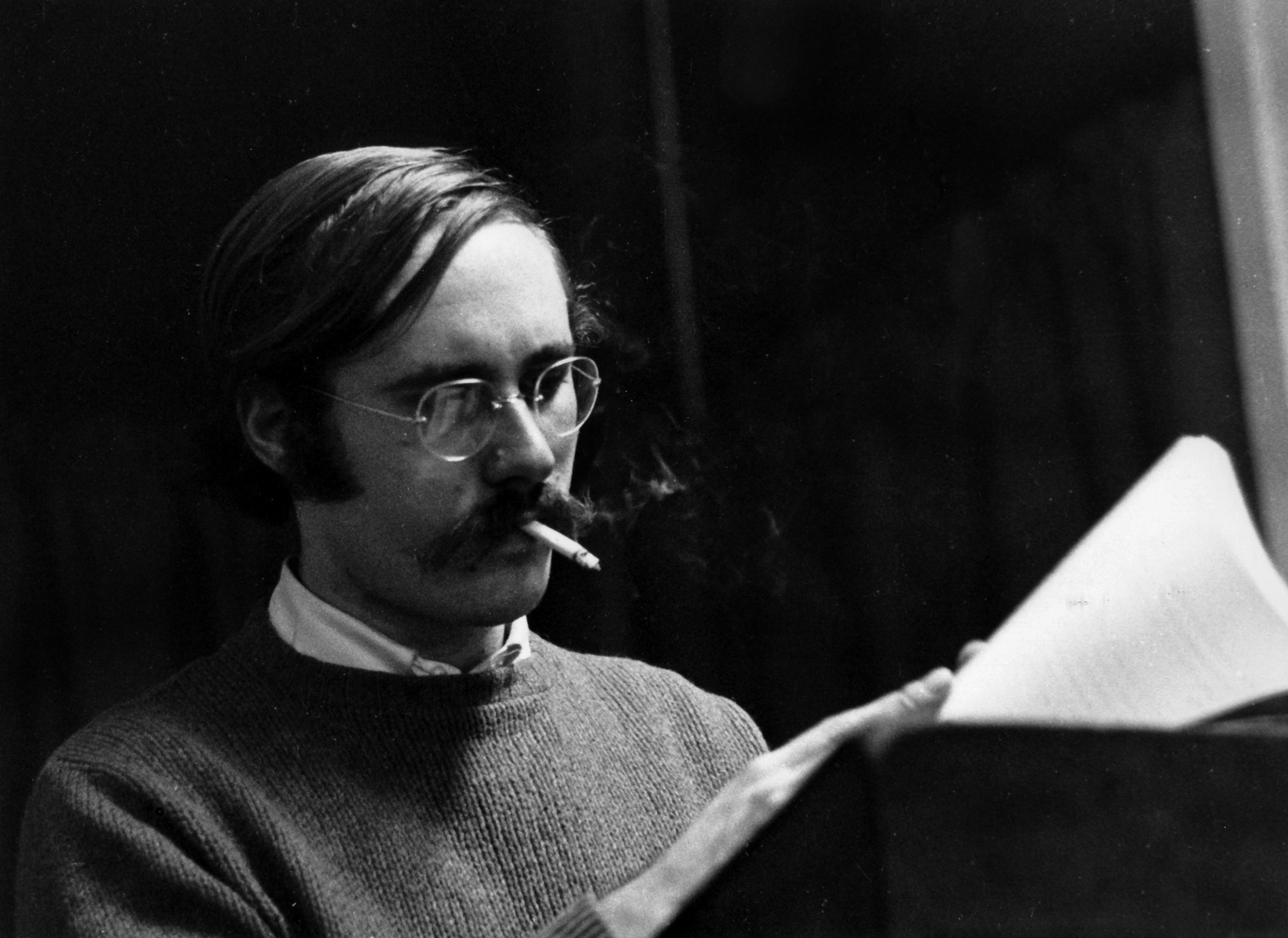

Robin Eichele

A LOVE SUPREME

The Red Door was quintessentially a group effort. If we had counted on just the half-dozen founders to keep it open, it might have lasted a month or two. Yet towards the end of our first (and only) year, Flint poet and WSU graduate student John Sinclair walked tentatively by the door, too intimidated by “all the beatniks in there.” Instead it took a chance encounter, in the spirit of Surrealism, for us to connect one afternoon on Second Avenue. As I stood at a corner waiting to cross, a tall, bearded hipster commented on the Coltrane album I was carrying, and the rest was fortuitous history. Within a few days, John met the gallery crowd, and proceeded to bring in his own friends, thereby vastly expanding our human resources. And when discussion turned to music and poetry, we discovered a world of overlapping interests: ‘Trane, Miles, Monk, Ornette, Mingus, Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp, LeRoi Jones, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Olson, Creeley, etc. John knew the southeast Michigan jazz scene better than any of us, and brought in drummer Danny Spencer, as well as prose experimenter James Semark, and countless others. Before the summer of 1964 was gone, a new group dedicated itself to a much broader venture, the creation of a communal performance space supported by three collectively rented apartment buildings (a true experiment in socialist housing):

…a place for artists — musicians, painters, poets, writers, film-makers — who are committed to their art and to the concept of community involvement to meet and work with one another in an open, warm, loving, supportive environment (what they don’t get in the ‘real’ world)…the success of which depends solely on those involved with it. To this end we have acquired a ‘studio’ workshop which will be maintained (rent, electricity, heat) by the artists themselves…4from The Artists’ Workshop Society: A “Manifesto” by John Sinclair, November 1964 (see Addendum).

Detroit Institute of Arts curator Mary Jane Jacobs’ excellent narrative of general DAW history is included in the catalogue for the 1980 exhibition, Kick Out the Jams: Detroit’s Cass Corridor 1963-1977. But much less has been written about an essential aspect of our lives in the Workshop’s first year: our intellectual concerns.

OLD SCHOOL / NEW SCHOOL

Among the theoretical underpinnings of Workshop activity, one was a text, the other a shared understanding. Charles Olson’s seminal essay, Projective Verse, insists (notably all in caps), “FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN AN EXTENSION OF CONTENT” — which opens a universe of poetic possibilities, away from an insistence on academic, closed forms (sonnets, sestinas, villanelles) and towards organic developments in form and the poetic line based on the poet’s breath (for example, the fecund differences in the “breathing” of a Ginsberg and a Creeley, a Whitman and a Dickinson, an O’Hara and a Levertov). The writers at the Workshop spent hours discussing the dozen pages of Olson’s manifesto, clarifying its implications for ourselves, and teaching it as part of the various classes we offered in the spirit of a people’s free school. Rather than limiting our explorations, as a set of dogmatic precepts might, the essay radically expanded them.

What this concentrated study afforded us was a fantastic jolt of enthusiasm, and an education absolutely not available then at any university. Above all, the accent at DAW was on self-education, a concept that came along simply because it had to. The air of early-Sixties America, despite so many new energies, was still polluted by a centuries-old elitism. I remember that when around 1962 I played a Ravi Shankar record for my Humanities prof (a relatively young guy), he asked me what it was. When I said, “North Indian classical music,” he answered, no, that it was folk music. Accordingly, jazz in “high culture” quarters, and because of its “low” African-American origins, was an object of derision, or suspicion at best. Robert Bly, in an infamous issue of his academic poetry journal The Sixties, gave the Tin Ear Award to Louis Zukofsky, one of the most amazing lyrical poets in American history. Meanwhile university poetasters all over the country were mired in the stifling orthodoxy of the T.S. Eliot-Allen Tate-Robert Lowell-John Berryman tradition. Yet these details of the landscape only intensified our contempt for the academy’s conservatism, and we reacted by trusting and informing ourselves.

French philosopher Jacques Rancière, in a groundbreaking text entitled The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation, discusses examples of self-instruction from early-19th-century Europe, and the revolutionary practices of working class students engaged in learning for themselves, on their own terms. Although Rancière’s book first appeared in 1987, more than twenty years after our DAW experience, he develops a unique understanding in it of key presuppositions of non-hierarchical learning. The institution of the university, as it has been constituted for centuries, is founded on essential inequality. Professors maintain a hierarchical system of explications, inevitable exclusions, and (dis)approval, often limiting students’ access to the very (disruptive, investigative) ideas that the latter desperately need. And the legendary boredom of the typical classroom derives, at least in part, from the situation of the professor with his overflowing bottle of knowledge that pours a tiny serving into each student’s glass of ignorance i.e. lack of experience.

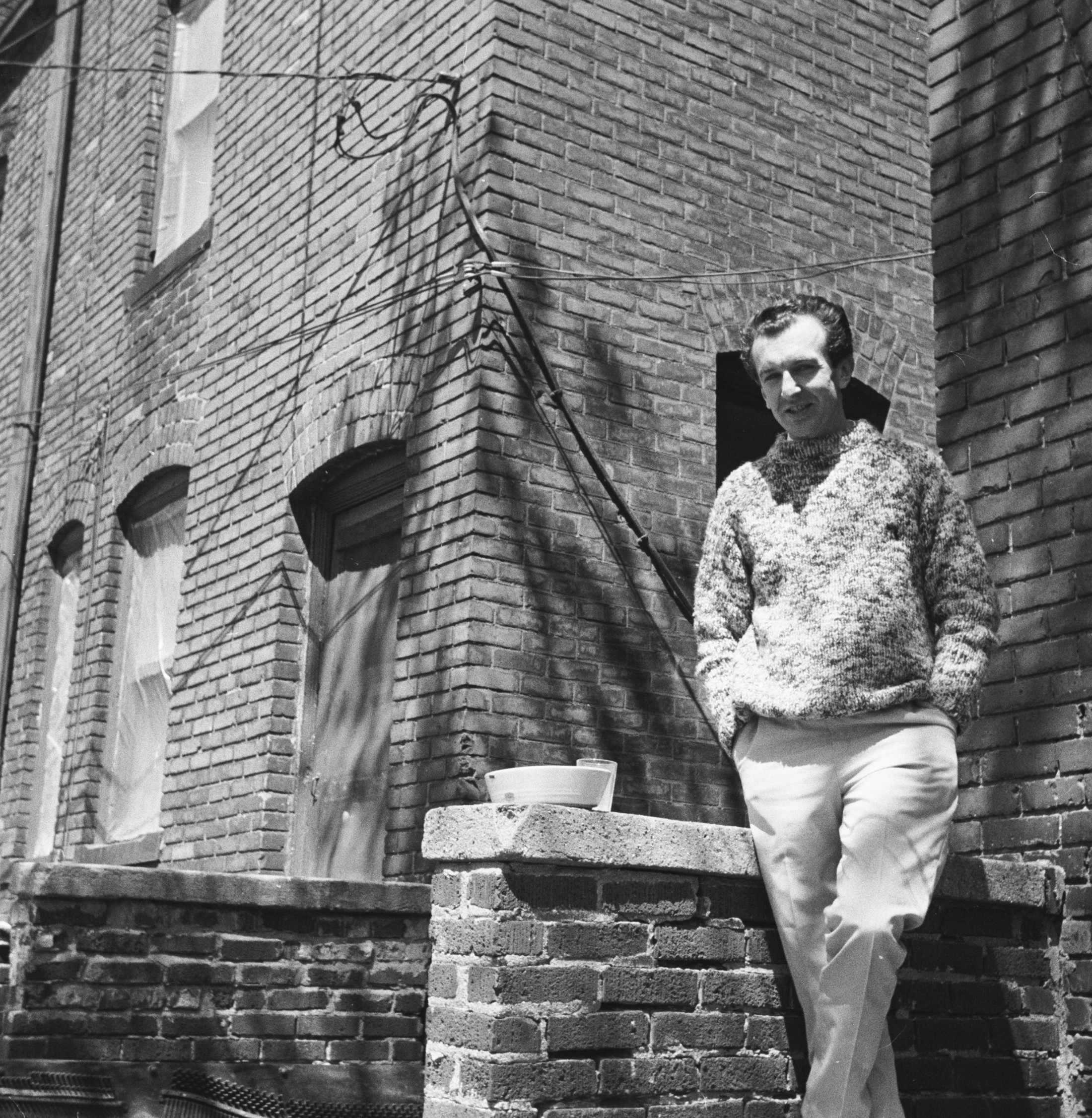

Leni and John Sinclair, 1964 (photographer unknown)

Rancière maintains that a pivotal notion underlying any project of collective enlightenment is that of the equality of intelligence:

We can thus dream of a society of the emancipated that would be a society of artists. Such a society would repudiate the division between those who know and those who don’t, between those who possess or don’t possess the property of intelligence. It would only know minds in action: people who do, who speak about what they are doing, and who thus transform all their works into ways of demonstrating the humanity that is in them as in everyone. Such people would know that no one is born with more intelligence than his neighbor, that the superiority that someone might manifest is only the fruit of as tenacious an application to working with words as another might show to working with tools; that the inferiority of someone else is the consequence of circumstances that didn’t compel him to seek harder. In short, they would know that the perfection someone directs towards his own art is no more than the particular application of the power common to all reasonable beings…5Jacques Rancière, The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation, trans. Kristin Ross (Redwood City: Stanford University …

By teaching ourselves, immersing ourselves in the ever-expanding search for poetry (or fiction, music, painting, photography, film, et al), we demonstrated to each other the power of will over intelligence — just as the best way to learn a language has always been to immerse oneself in the community of that language. And those of us who worked a little harder would discover that the French word poésie is poezja in Polish.

When I first read Jack Spicer’s The Holy Grail in 1964, it puzzled, seduced, and inspired me in ways that I couldn’t have imagined in 1959, when my experience with poetry was a few works by Walt Whitman and Langston Hughes. Of course, in the interim I had read Ginsberg, Creeley, Duncan, Olson, Zukofsky, LeRoi Jones, etc.etc. But there also was no exam forthcoming on Spicer, no professorial explication, no right or wrong way of reading him, just my will and passion. Into a matrix of King Arthur, Lancelot, and the Round Table, Spicer drops references to Tarawa (the horrific 1943 battle between US and Japanese forces), Las Vegas, the Wizard of Oz, etc.6My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer, ed. by Peter Gizzi and Kevin Killian (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2008).

It was entirely up to me to work with all that, and then share the fruits of my labor with others.

At various times and intensities, our collective reading list included, among many other titles: Creeley’s For Love and his novel The Island (his emphasis on the rhythms of speech and thought); Olson’s Call Me Ishmael, The Maximus Poems, and Human Universe and Other Essays (his call for an engagement with the body politic and a poetics of immersion); Robert Duncan’s The Opening of the Field (the intense focus on modern lyricism); Jack Spicer’s The Heads of the Town Up to the Aether, The Holy Grail, and Language (his concept of taking dictation from inside and “outside” the language); Denise Levertov’s With Eyes at the Back of Our Heads (its formal, lyrical radiance); Gary Snyder’s Riprap and Myths & Texts (the focus on wilderness, Zen meditation, and the materiality of the line); LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka)’s The Dead Lecturer and Tales (his commitment to a community-class analysis, as well as the inflections of free jazz); Louis Zukofsky’s All: the Collected Short Poems, A Test of Poetry, and Bottom: On Shakespeare (his exquisite ear and example of not throwing out the baby — Catullus, Shakespeare, the Metaphysical Poets — with the academic bathwater); the novels of William Burroughs (the centrality of the cut-up method); Ginsberg’s ecstatic Howl, Kaddish, and Reality Sandwiches (his debt to Surrealism, the Hebrew prophets, jazz, and the compositional idea “first thought, best thought”); John Wieners’ Hotel Wentley Poems and Ace of Pentacles (painful lyricism for the ages); Frank O’Hara’s Meditations in an Emergency and Lunch Poems (his Whitmanesque embrace of life, our times, and poetic invention); William Carlos Williams’ Spring and All and Paterson (maybe the father of us all); and various writings by Wilhelm Reich, Buckminster Fuller, Rachel Carson, Carl O. Sauer, Malcolm X, A.B. Spellman, Jonas Mekas, Diane di Prima, Philip Whalen, Gregory Corso, Hubert Selby Jr., John Rechy, Jack Kerouac, Douglas Woolf, Fielding Dawson, ad infinitum.

The writers of the Workshop — Robin Eichele, Bill Harris, James Semark, John Sinclair, Allen Van Newkirk, Jerry Younkins, and I (among many others) — published our work in the form of chapbooks, broadsides, and magazines (notably, WORK, focused on writing, and CHANGE and WHERE, on music) under the auspices of the Artists Workshop Press, a mimeo affair run by Robin, and graced with photos by Leni.

However, the virtually unavoidable consciousness we shared was of an America gone insane with repressive violence. By the end of March 1965, JFK, Malcolm X, and Viola Liuzzo had been murdered, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., Robert Kennedy, George Jackson, countless Black Panthers and other activists were soon to come (a leitmotif stretching to 2015). What we treasured in jazz, America’s indigenous avant-garde, were its roots in an oppressed but uncowed community, its resistance to the consequences of slavery, and its joyous stance when it came to collective, spontaneous creativity. Yet jazz for us was an intellectual model as well. Just as John Cage awoke us to indeterminacy and silence (that all sounds, including those of the widest varieties of language, could be music), and Charles Olson proposed a dialectics of projective verse (that poetic form was a matter of existential choice for the poet), so Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, et al proposed the life-affirming adventure of improvisation. We embraced their indispensable connection to contemporary thought and writing.

THIS IS OUR MUSIC

Although I’m giving short shrift to the DAW music scene, I’ll never forget the emotional-conceptual impact on all of us of the Detroit Contemporary 5 (Charles Moore, trumpet; Larry Nozero, tenor sax; Ron English, guitar; John Dana, bass; and Danny Spencer, drums). We poets may have been fledgling, but the band’s free jazz took everybody higher. Each Sunday afternoon, writers and musicians performed for a packed crowd, one that included Larry Weiner (who had become a filmmaker), Ellen Phelan (the WSU art student who became an internationally renowned painter); Leni Sinclair (who married John, and brilliantly photographed Workshop activities and Detroit arts in general); and such other resident musicians as Pierre Rochon, Harvey Robb, and Ronnie Johnson, as well as visiting poets Clayton Eshleman and Robert Creeley, Toronto poet Victor Coleman, jazz superstar Charles Lloyd (who jammed with the DC5), and eventually the Art Ensemble of Chicago (who stayed in residence for months), then the proto-punk MC5, as the DAW directed its attention to the insurrectionary role of rock.

Long-term offshoots of the Workshop have included Ann and Ken Mikolowski’s generous, expansive Alternative Press, the encyclopedic Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival, the White Panther Party, Trans-Love Energies, the Strata Concert Gallery, WDET-FM’s poetry broadcast “Dimension,” and LINES: New Writing at The Detroit Institute of Arts (1980-1991), all dedicated to an ongoing awareness: the united intelligence of the people will never be defeated.

As 21st-century Detroit arises from the ruins of exploitation, the transformative role of its artists and art projects will be in the relationships they forge with the community at large. Henceforth, we refuse to consider the practice of art simply as a professional meal ticket or the production of investment objects for the ultra-rich. The historic antecedents to such an awareness are many: we look to the engagement of the Russian Constructivists, the experiments of the French Situationists, the voluminous writings of Jacques Rancière on the politics of art and education, and the homegrown efforts of the mid-Sixties Detroit Artists Workshop to rethink our difficult surroundings.

ADDENDUM

THE ARTISTS’ WORKSHOP SOCIETY: A “MANIFESTO”

/ John Sinclair

1 NOVEMBER 1964

Why a community of artists? We believe that one of the most important things to a young, formative artist is having a group of his peers (in the best sense of the word, taking into consideration his advanced level of consciousness &c), that he can be a part of, that he can talk to, work with, work out ideas, &c and can give him support. Modern society has succeeded to a frightening degree in alienating artists from each other (and of course from people in general; or at least vice versa) and atomizing what could be a vital, active community into a group of lone, defensive, hung-up people who are afraid to talk to and/or work with anyone but themselves and (maybe) three or four friends.

A community of artists means that a group of highly conscious people have resolved their individual, ego problems and can help each other in very real ways – by giving support, stimulation &c. The artist working alone is cutting himself off from (though not consciously I’m sure) from sources of inspiration and influence that can help him immeasurably in his work. The lone artist has no one to listen to his work (LeRoi Jones: “how you sound”), no one to offer criticism, ideas &c that would bring his work into sharper focus with itself. He stumbles along, hung up in his own ego & his own work, no perspective, he can only listen to the generations before him & those who are getting exposure now (if he knows where to find them on his own) to get his inspiration & perspective – solitary, at best an artificial situation. Hard to get as excited, as completely involved in his work by himself; when he can talk about it with/to others who are trying to do the same thing as himself (i.e., create some poetry (read: beauty) “out of the garbage of their lives” (LeRoi) and communicate it to others) he can achieve and maintain the state of consciousness Henry James called “perception at the pitch of passion.” And who better to communicate to than those few people who are operating at the same level of awareness and involvement as oneself?

Poetry (or any art), does not need to be “sullen” (solus: alone) any more. We are now in a period of expanded consciousness in all the arts, the most immediately important aspect of which is the transcendence of what is understood as the “ego” (in the accepted – worst – sense of that word). Left alone without any real criticism (i.e., “constructive” criticism from those who are involved in the same thing you are, not from dilettantes & culture/vultures, ‘art lovers’ &c), the artist’s peculiar ego swells, he becomes deadened to his mistakes, he, after a while can’t bear real criticism, he’s defensive, gets more atomized, separated, alone, can’t talk to anyone, everyone else is crazy: becomes (alas!) the old “romantic” figure, misunderstood, one man against the world – no good. NOW is the time to find out what’s wrong with your work, NOW, at least get an inkling of what other real people will think of it, how it communicates, &c.

Another vital aspect of community thinking: each individual involved must (– has to – ) learn a sense of personal responsibility: must take an active role in the life of his community, assume its problems and (this is too difficult any more) its rewards & achievements, as his own, pitch in and help those around him who are trying but who haven’t succeeded in getting themselves together as soon as he has. This is not like trying to work with (convert?) straight people (i.e., non-artists) – they have too far to go anyway, hard to really help them, they aren’t in a supportive environment, they have to go home at night, no good, they really have not got a chance to make it. Artists, conversely, do have the very best chance to achieve higher & more productive levels of consciousness: they exist, for the most (& best) part, outside the existing social system, aren’t hung up by pettiness, have a chance to really get into their work, the best chance – by virtue of their distance from what its pitiable inhabitants call the “real” world (bombs, bureaucrats, greed, politics, “what filth deals consummated in what lavatory to take what is not yours” – [William] Burroughs), artists can transcend that swamp of artificial reality and have a chance at putting love and help into action in making their own reality.

So: what we want is a place for artists – musicians, painters, poets, writers, film-makers – who are committed to their art and to the concept of community involvement to meet and work with one another in an open, warm, loving, supportive environment (– what they don’t get in the “real” world) – a place for people to come together as equals in a community venture the success of which depends solely upon those involved with it. To this end we have acquired a “studio” workshop which will be maintained (rent, electricity, heat) by the artists themselves, through individual subscriptions of $5.00 each (i.e. initial investment – the pledge will be adjusted, on a monthly basis, and probably downward, as the Workshop program is totally implemented and we have a concrete figure for maintenance costs.) This method of supporting the Artists Workshop is necessary, we feel, because:

1) Each member of the Workshop is to assume an equal responsibility in the project’s success;

2) Members have to go into their already near-empty pockets, thus the project cannot be treated lightly;

3) We feel that any commercial means of support, at least (& especially) in the beginning, would tend to create an artificial community hung together on money, rather than a genuine community built on mutual need and mutual support and interest;

4) No “outside” pressures, hang-ups, interferences;

5) The Workshop ideal can be maintained, i.e. there will be no pressure on artists to produce work that would have commercial success, rather than integrity and aesthetic honesty, as its ultimate purpose.

We do believe, however, that commercial ventures will come into being as logical and desirable outgrowths of the Workshop as it has been conceived and as it is now operating. For example, we can see in the future a coffee shop where musicians would present their work; a gallery for painters and other graphic artists to exhibit their work; a small printing and/or publishing concern through which poets & writers could introduce their work; an operating film society that would enable local film-makers to produce and possibly market cinematic ideas.

Other individual projects that are being planned as part of the workshop’s total program: lectures on modern music, painting, poetry and film, by the artists themselves, that would serve to introduce & enlighten an often-puzzled public to the artists’ aims, purposes, & finished work; free jazz concerts and workshops, featuring in particular the work of Detroit’s musical ‘avant-garde,’ with commentary on their work by the musicians themselves and by enlightened critics & students of the music; interpretive poetry readings, with background and explanatory commentary by the poets; screenings of films by Detroit experimenters and by independent film-makers from New York and San Francisco who are involved in what has been called the “New American Cinema,” and whose work is not readily available, via commercial theaters, to its eager audience. All these will be “free,” non-commercial affairs that are planned, programmed, & produced by the artists themselves.

We sincerely believe that our Artists Workshop Society can and will succeed: the time is over-ripe, the people are ready to convert their ideals into real action, there is no real reason why we can’t make it. We need all the support we can get, especially your spiritual support and blessing; we are trying to establish ties with the isolated groups of artists that exist in this country and throughout the universe, and we sincerely wish to cooperate with anyone who will let us. Please help.7Also see www.detroitartistsworkshop.com for a wealth of information, documentation, and first-hand testimony on the DAW phenomenon.

ARTISTS WORKSHOP SOCIETY

JOHN SINCLAIR

CHARLES MOORE

LARRY WEINER

JAMES SEMARK

GAYLE PEARL

ELLEN PHELAN

BILL REID

JOE MULKEY

ROBIN EICHELE

GEORGE TYSH

DANNY SPENCER

RICHARD TOBIAS

ALLISTER MCKENZIE

PAUL SEDAN

DAVID HOMICZ

BOB MARSH

John Wieners at the Artists Workshop in 1965

References