A Midwife to Ideas: Tony Hepburn

Addie Langford

… to see and to work – how different they are here. Everywhere else you see, and think: later-. Here they are almost one and the same. You’re back again: that’s not surprising, not remarkable, not striking; it’s not even a festive occasion; for a festival would already be an interruption. But this here takes you and goes further with you and goes with you to everything and right through everything, though lesser and greater things. All the things of the past rearrange themselves, line up in rows, as if someone were standing there giving out orders; and whatever is present is utterly and urgently present, as if prostrate on its knees and praying for you …

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letter, June 3,19071Rainer Maria Rilke, Letter of June 3, 1907, Letters on Cézanne, trans. Joel Agee (London: Jonathan Cape, 1988), 3.

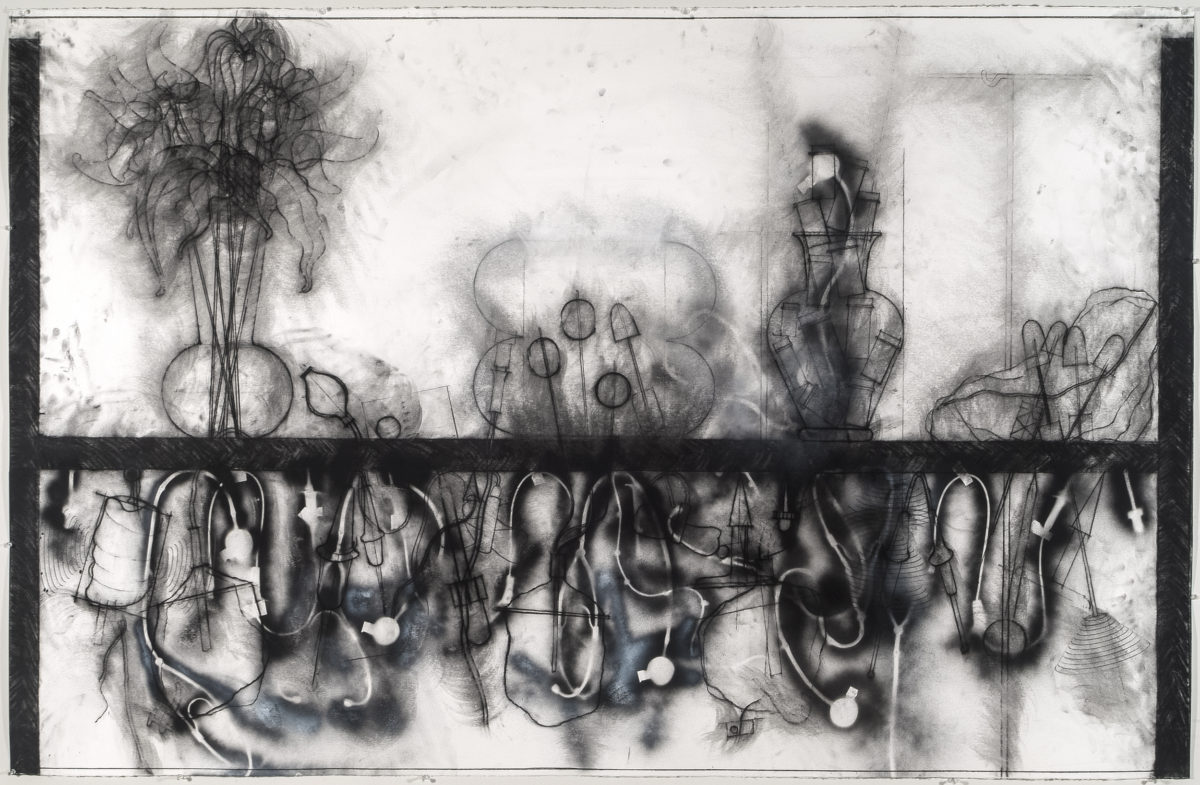

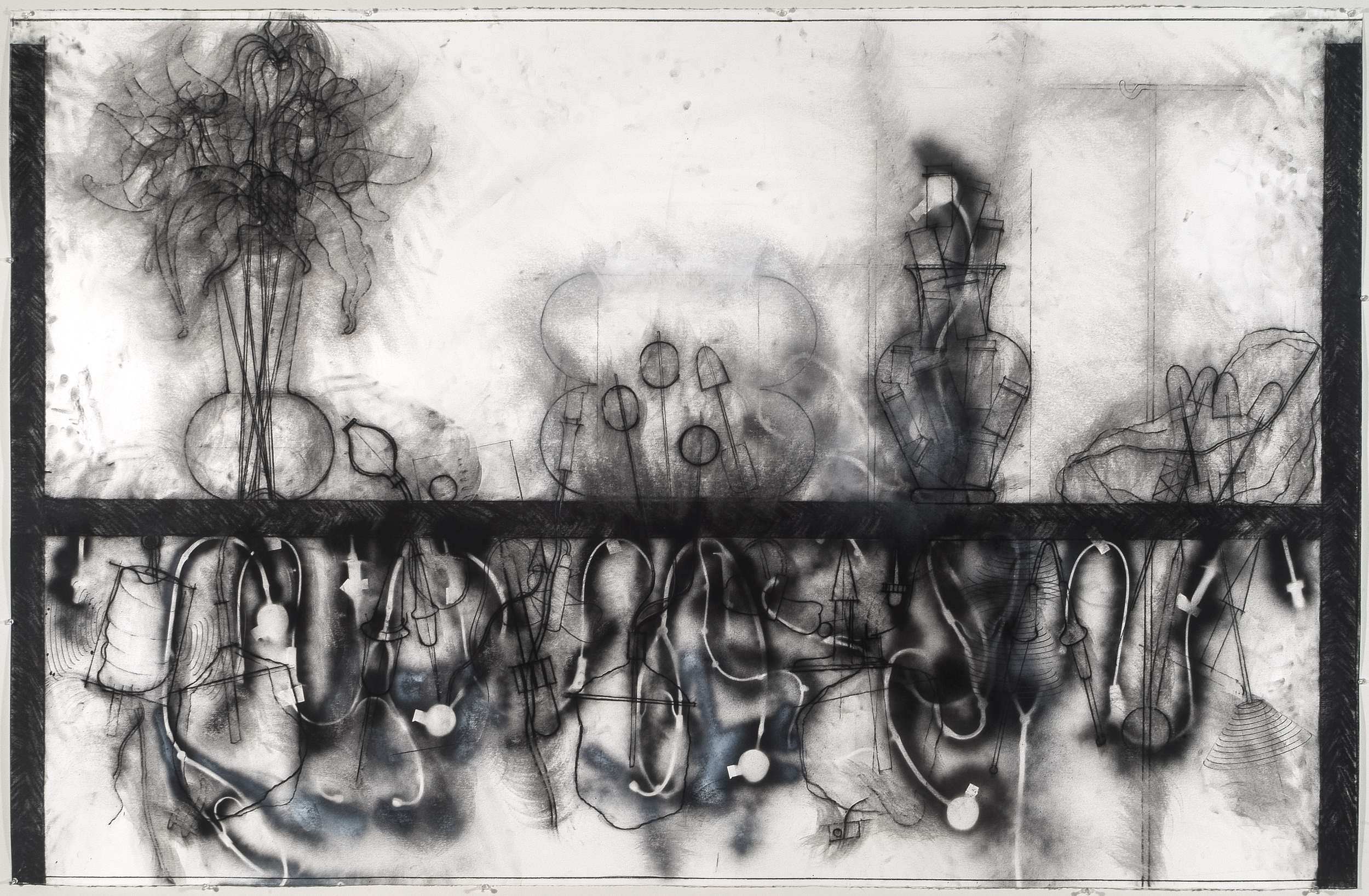

Tony Hepburn, Catheter, 2004, charcoal, conté, acrylic on paper. Photo Tim Thayer.

Collection of Detroit Medical Center/Huron Valley-Sinai Hospital.

Detroit Research would like to pay tribute to Tony Hepburn for the multiple ways his life as an artist and educator has impacted Cranbrook, Detroit, the field of ceramics, and countless students. He represents so many things this journal stands to foster, only one of these things being a commitment to ceramic art in its multiplicity.

Because of his capacities as a thinker/maker/artist/educator/cultural agitator, Tony Hepburn can only be reflected through a kaleidoscopic lens of a few people who knew him well. Paul Kotula, gallerist and university professor, started out as his student at Alfred, then Cranbrook, then became Tony’s gallerist in Detroit at Revolutions Gallery, and now holds a place as a long-time familial best friends to Tony and his daughters Laura and Abigail, whom we thank for their generosity in allowing us to share use images from the Hepburn estate. Marsha Miro is a long-time art critic, writer, dear friend of Tony, and former archivist at Cranbrook where she came to know in detail the institution’s architecture, old and new, and Tony’s role in that history. In friendship, Marsha and Tony co-authored a book on Robert Turner, arguing a place for a poetics of craft, namely ceramics. They sat together for hours the summer his hip was replaced – sharing notes on the arch of Tony’s educational career. Marsh co-founded the Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit (MOCAD) that same summer, and oh, if we could have been privy to those patio conversations. We will hear from Tom Laureman, one half of a dynamic duo, his wife and former Hepburn student, Shannon Goff, both alums turned great friends of Tony, and becoming leading national artists, two of Tony’s most prized. Ben Teague, also a former student has a perspective that lends insight into the aspect of Tony’s teaching that felt like deciphering a sort of poetic riff or riddle. It is worth noting that Tony didn’t deliver lectures but dropped sparing utterances like philosophical bombs, which you were sometimes ready to receive and many times not. Ben filled our Cranbrook years with blues and bluegrass on his mandolin for which he is now well known locally and beyond, and combined this with whittled ceramic fragilities. Tony was delighted by combined talents – collage, hybridity, complexity. It is no surprise that Ben retains Tony’s wisdom and stories in narrative and lyrical fragments. Not speaking in their own voice, but featured in this volume of Detroit Research are several ceramic artists of the younger generation. First, Jessica Stoller, a Hepburn student (Class of 2006), whose work is taking off in New York. There is a feminist perspective to her work in the way that it closes in on the figurine as vehicle for exploration; and there is also considerable formal virtuosity in the way in which it calls upon Dresden and Meissen ware to ends other than those normally associated with Dresden and Meissen ware. P.P.O.W. Gallery has emerged as an early supporter of Stoller’s work and New York is starting to take note. Stoller, with her discomforting figurine language, is 180 degrees from this volume’s featured artist, Detroit resident, and Danish rising star Marie T. Hermann, a potter educated in the Scandinavian / British pottery traditions (including the studio of Edmund de Waal). Hermann’s work is a collision of function and installation which creates space for the potter’s potter and the contemporary installation devotee to enter the work. Her vessels, sometimes filled with an elevated subfloor inside, sit as still life on small shelves with enigmatic blobs and recently hanging rubber puddles.

As I wrote in the 2006 Cranbrook yearbook, Tony was an atmosphere you enter. His influence on each of us was complex, for some complicated, but as the Spanish say, impresionante. Hybridity. This was the second word I recall Tony imprinting on us after velocity. Evidently these were the words he used to walk a new class down into the two-year mist. These terms defined his practice as artist and as educator / guide. He was enchanted by the work and pose of Joseph Beuys as the shaman or the mystical was central to his approach in conversation.

His background in philosophy made him open to poetry and a thinking of the fragment. As students we were liberated and terrorized by his acceptance of unsure or middle spaces. He pushed students to consider or articulate in detail the nature of the experience of misunderstanding and not knowing. His tendency to conduct conversation just beyond our register kept us falling forward as a group. (Somewhere, thinking of the Austrian poet Georg Trakl, Rilke speaks of falling up…) Daily references to Derrida and Heidegger, Adrian Stokes …

If he tried to convince us of anything, it was to resign to a certain ambient anxiety native to creative work. To stay in motion (in mind or hand, depending) was the work, and to keep arriving at a more sophisticated unknown could be seen as success. – Though it is dangerous to try to define Tony’s thoughts or beliefs in a way that might sound like a statement of fact, I am trying to get at the atmosphere of learning he created, yes, distinct for each of us, but there were constants in his approach. Somehow he crafted a void of uncertainty into a solid experience of something.

Cranbrook, it should be known, does not use a curriculum, and for this reason Tony did not see himself as a teacher – the position he occupied was that of Artist in Residence. To educate is not necessarily to teach a curriculum. The absence of regularized instruction was replaced by his quiet charisma and a deep knowledge that avoided showiness of intellectual stand-offs. The past decade has taught me much about leadership at its best and worst, and as a result I have come to appreciate his nuanced ability to influence others. Clay, not the hippest department on the art block for the past sixty years, was wait-listed with students from other departments seeking independent study. He took only two or so per term. The energy drew them, the attention, the conversation, the quality of professionalism and solidity in critique. No one was late, used profanity, bullied, or skipped. He crafted a department of elegance, intensity, and range.

In addition to a Socratic quality he was puckish, mischievous, clever, elfin, and rebellious. Tony enjoyed more than a pinch of studio tension and admitted disappointment when the groups were too Kumbayah – he believed people, objects, and material in tension created a hybrid, electric space, a place requiring negotiation. Taking a line from the correspondence published below, Tony referred to the Scripps exhibition he curated in California in 2007: “I was pleased with the show […] I think it made the point I was after and just the right number of people had a problem with it.” If everyone was happy, he assumed it hadn’t been pushed far enough. But, his contrarian nature was permissive. We would listen to the stories he rolled out – there were guns, and bears, and a couple of near-misses in South America. The nervous energy of arriving students renewed his appetite for adventure, and it was shocking and thrilling to see that he was just as edgy about his own emergent work as we were.

Generations of students had the Tony who delivered British parliamentary blows and magic in equal measure, but my class came to Tony a few short months after the loss of his beloved life partner Pauline Hepburn, an incredible painter, a woman whom I never met but whose legend and loss we came to live with. I’ve been told by many that this was a turning point that softened and deepened his relationship to students, and that we had an experience that was profoundly marked by his growing closer to multiple conclusions – I see this more clearly now. In 2006, sixty students and friends convened from all over the US and abroad to celebrate Tony’s 40th year in teaching. It was a twinkling experience and within a year Tony retired and moved to Chicago. Having now met many who passed through Tony Hepburn’s studio I see people whose aesthetic selves seem to have been cracked open and rebuilt on one’s own terms – no one’s work looks like another’s. That anniversary gathering made visceral Tony’s role as conduit and it was palpable how his impact was life affecting, various, and indelible.

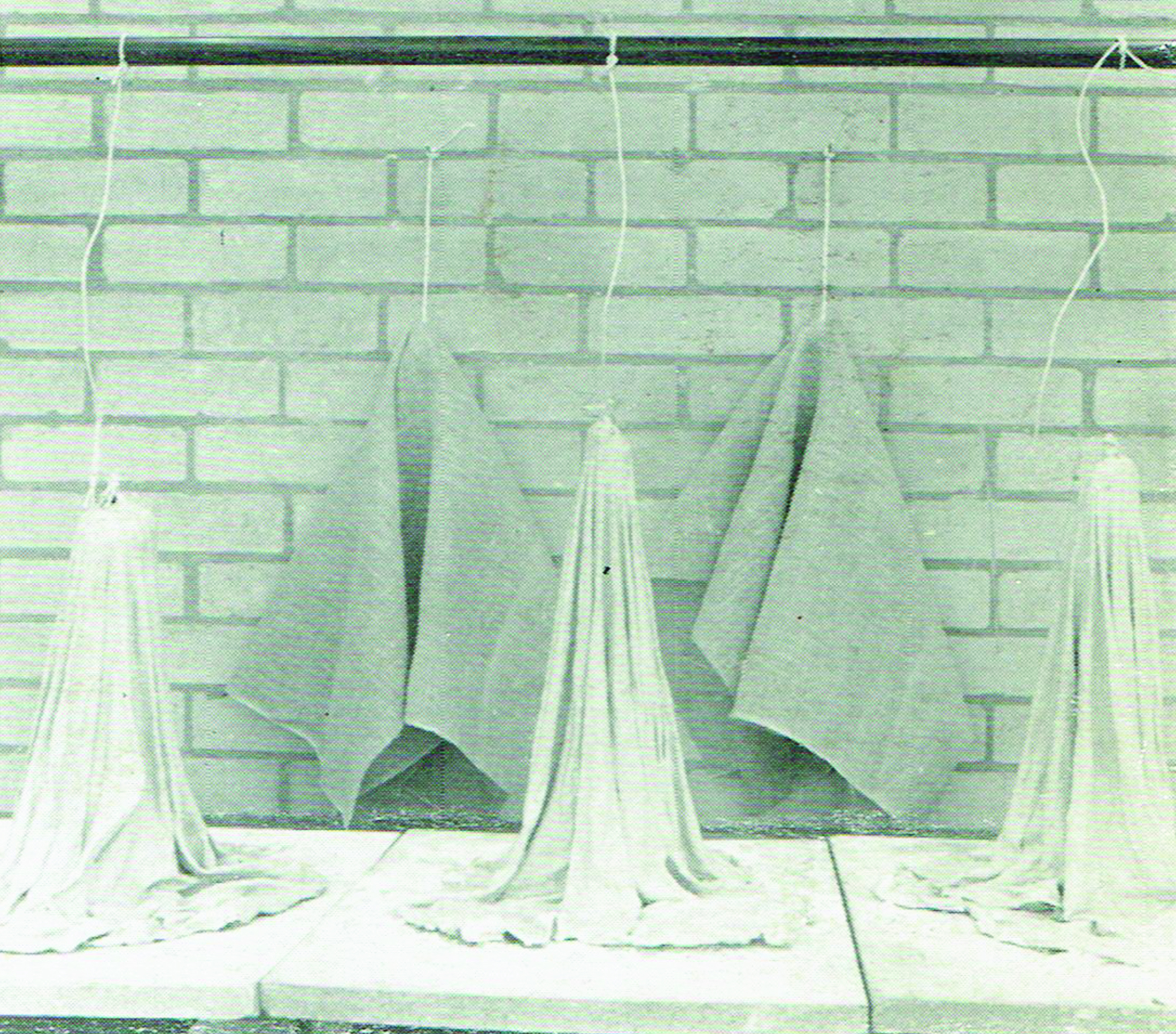

Tony Hepburn, M.P. 7, 1971, cloth, clay, string.

Though ceramic traditions weigh heavily on the hand, Tony Hepburn located making equally between the hand and mind – here, seeing and thinking are one, as Rilke observed of the advanced art of the Paris of his day – yet Tony appreciated any approach to art that had magnitude and direction. There is an aspect of the intellectual and the sensuous thinker in Tony’s make-up that has not been fully appreciated. Here we might think of his admiration for Richard Tuttle which he expressed often including in a letter to me and with whom Tony’s work was clearly in dialogue – see, for example, M.P. 7, 1970, cloth, clay, and string as shown in Recent Work (Materials Pieces), 1971 at the Camden Arts Centre in London, a work that could easily have joined Tuttle in Harald Szeemann’s great exhibition When Attitudes Become Form at the Kunsthalle in Berne, Switzerland in 1969. Though not fully appreciated by many ceramicists, we should also recall that Tony was a member of the influential British avant-garde group Art + Language and had an especially close relationship with Art + Language member Terry Atkinson who also taught at the Coventry School of Art (later Lanchester Polytechnic) as a colleague of Tony’s. As a new generation of artists and scholars of art writing come to Tony’s work it might well be in these unexplored directions – of Tuttle, Atkinson and Art + Language – that is, the conceptual directions, that fruitful explorations of Tony’s thought and work can be undertaken. This combination of the conceptual and the sensuous, of the quest, was fully embodied in his teaching. He did not need to like what you as a student had made but rather to understand what moved you and then to see you plow further into that territory. Tony lived the Socratic method in that he was he was a midwife to ideas, and trusted that we arrived with what we needed, and so never told us what to do or not do, but rather took us orienteering and tracked us with wolven senses, but knew when to extend a helping hand, and when to let us go.

It’s taken ten years to understand what I learned from my mentor, and how he taught it to me, but I see now that part of what he knew all along was how hard it is to define one’s self (to one’s self), then to set about constructing an ongoing set of challenges and parameters to achieve something in a field where nothing is right and nothing is wrong, but where there exists a definite way of doing things – it’s all so non-linear, and most are not equipped to cope – in short, to be an artist. Knowing this, he crafted a ropes course of learning to hone a killer instinct of self – understanding that can be used in all trials and trades. The enormously courageous (like Tom and Shannon, Paul, and Jessica) charge to the top of their field (Tony’s list of protégés is long), and the others leave his orbit having established a stronger core to do other fascinating things in the world (the MFA is the new MBA), these alternate paths, he clearly respected, Art and life, he would say.

When Tony was slowed down by his hip replacement he edited about twenty versions of my Fulbright proposal (in exchange for trips to fetch lamb chops and asparagus). In thanks, and a need to share, I wrote letters from Spain, to which he responded. In the writing and reading of letters there is so much space to hear someone else, and to be heard, and the beauty is to read them over time and realize how much you missed the first go around. The letters (included below) Tony wrote to me while I was in Madrid open a window onto the time and attention he offered his students – the unspoken contract that as long as you were still seeking, his door remained open. Once a student, always a student, as long as you kept the line open.

So here is a toast, an offering of writing, images, and stories in tribute. A section in this journal was the least we could offer to mark the immeasurable contribution to the creative life of his family, students, his field, and community of artists from Mexico, to China, and back to Detroit. To Tony Hepburn, to art and life.

References