A Dancerly Divining Rod

Biba Bell

[D]ance, as a scenic event, is directly shaped by such a structure. Its own works have no other milieu of existence but the scène, and this one, as we hope to show, is nothing else but a structure of contemporaneity and therefore a structure of temporality.1Frédéric Pouillaude, “Scène and Contemporary,” in Planes of Composition: Dance, Theory, and the Global, ed. Jenn Joy and André Lepecki (New …

Similarly to how she flexes her muscles, a person flexes her surroundings—both are with her and of her always.2Madeline Gins and Arakawa, Architectural Body (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2002), 40.

Dance is in and of its scene. Setting, mise en scène, or theatrical context, perhaps we could imagine choreography itself, an “apparatus of capture,” as one of dance’s primary scenes.3Choreography is referred to in relation to the term “apparatus” by numerous scholars, notably André Lepecki in his discussion of choreography as … Choreography moves us into the frame of the architectural, the topo-geographic, and the social. Expanding the scene, all the world’s stage, we continuously move with and against the world. Dance takes place through its refusal to stay in place. Rhythmic, gravitational, corporeal, affective, dance moves us. The dancer partners the city in what might event a Jacobs-esque sidewalk pas de deux or it could look more like a social choreographic act of resistance. Here, the city is all that it contains: an ensemblic sphere of bodies, vehicles, buildings, green spaces, day and nighttime rituals, economies of circulation and capital, of desires and relations, discourse, difference, and the rich, layered strata of historical memory. Frédéric Pouillaude, quoted above, invests the scène as a structure of temporality predicated on contemporaneity and, thus, contingent co-existence. The dancerly scene requires this essential co-existensivity and, tuning into its eventness, this is a nexus across which multiple temporalities converge. It is a multivocal and complex terrain—marked, grooved, uneven, populated, and replete with potentiality. Choreographically, it is a space of inscription that puts into practice the many ways bodies organize and are organized.

Conjure the image of dancer as alchemist, ambassador, or ninja. Whether feeling the rub in a tight, sweaty room or bounding across open-air, grassy lots, there is a way that the body moves to reset the stakes in a site, shift its fault lines, and dis-articulate spatial stratifications. At times these are exalted, extraordinary feats and at times simply everyday, ambulatory play. This figure is one of many, never quite alone, calling and responding to an ensemble of dancers past, present, and future who join together in rhythm, breath, and energy. Yvonne Rainer once noted that dance is very difficult to see. Instead, can you feel it? Hear it? Tap-tap, slide, chassé, step, step, stumble—feet against the floor—four-on-the-floor—“Every cell knows where down is. Easily forgotten.”4From a transcription of Steve Paxton leading his “Small Dance,” aka “The Stand,” Contact Quarterly, 11.1 (Winter 1986). From the ground up, let us dance with improvisational quickness, dexterity, urgency, enjoyment, and care.

* * *

Setting the scene. It was a Sunday morning in March in 2013 when Ralph Lemon and I shared a memorable walk around a very special building in Detroit: the Motown Museum on Grand Boulevard. Ralph was visiting Detroit as a guest artist at the University where I teach. Approximately twelve years earlier, when we’d first met, he had been deeply engaged in a process of “backyard” research through the American South. During this period, which came to form Come Home Charlie Patton, the third part of his seminal Geography Trilogy, he investigated intersections between identity, race, and geography.5Cf. Ralph Lemon, Come Home Charlie Patton (Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 2013), 180.. Dance offered a means by which to peer into and map the silent memories of history, a corporeal divining rod detecting history’s ephemeral voices, and invoke what José Medina refers to as “people who remember against the grain.”6José Medina, “Toward a Foucaultian Epistemology of Resistance: Counter-Memory, Epistemic Friction, and Guerrilla Pluralism,” Foucault Studies, … Music was also central to this journey. At the time of our Detroit outing, Ralph had recently curated a performance series at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City that took its title from a gospel song, “Some Sweet Day,” and sparked lively discussions about what happens when dance steps into the aesthetic, economic context of the museum.

Needless to say, I expectantly anticipated our visit to Hitsville USA. For me, coupled with the Rouge River Plant, the site endures as a fertile archive of Detroit’s significant contributions to dance history. While some might argue that dance is not the focus of the Motown legacy, unless of course we are talking with the ghost of Cholly Atkins in the room, it is a major presence in its scene. Dancing in the streets, music is catchy—an enduring vessel for dancerly contagions. Gordy took this into account and choreography’s house was established in the compound wherein some of the most significant performers of the 20th century were nurtured. Dance offers an important lens to flesh out the very real, virtuosic ways these artists engaged the politics of embodiment and identity as they traversed multiple spaces and aesthetic economies. Additionally, this scene resonates with a number of themes that run through my own scholarly and artistic research: performance, affective labor, and domestic space. That Sunday morning we pulled into the funeral home parking lot next door, got out of my jeep, and found, to our dismay, that the museum was closed.

Instead of driving away we stood on the front lawn and read the historical plaque detailing the landmark site. A display window on the front of the East sitting house advertised the current exhibition. A trip to the museum is invariably furnished with a tour, and through the years I’ve come to remember a bit of script, which that morning I tried to relate to Ralph. I pointed to some of the other houses in the neighborhood that once formed the extended Motown compound, including a big white home two doors down (“the money house”) where artists went to get paid. I described Gordy’s private residence in the upstairs apartment and its 60s style modernism, remembering an image of what might have been a forrmica tabletop or a plastic cup filled with resin to look like a half finished glass of pop. We began to circle the building, peering into windows and over fences, running our hands across the painted brick walls, and made our way around the house to the back alley where the garage had been converted into Hitsville’s legendary Studio B with help from Gordy’s father. From this vantage I did my best to remember what was inside: the location of the piano, the recording booth, a wall-hook where the Temptations hung their coats, a suspended microphone under which stood a young Diana Ross. The home came alive for us as we imagined elated play coupled with diligent work. We patiently solicited its memories, listening for that echo-y Motown sound and hoping for a bridge. Our methodical choreography circling the homes lasted for close to 30 minutes. Pedestrians passed by, walking along the boulevard, and perhaps wondered what we, two dancers, two researchers, two friends, were doing creeping around that house, a mecca of Detroit’s performance history.

* * *

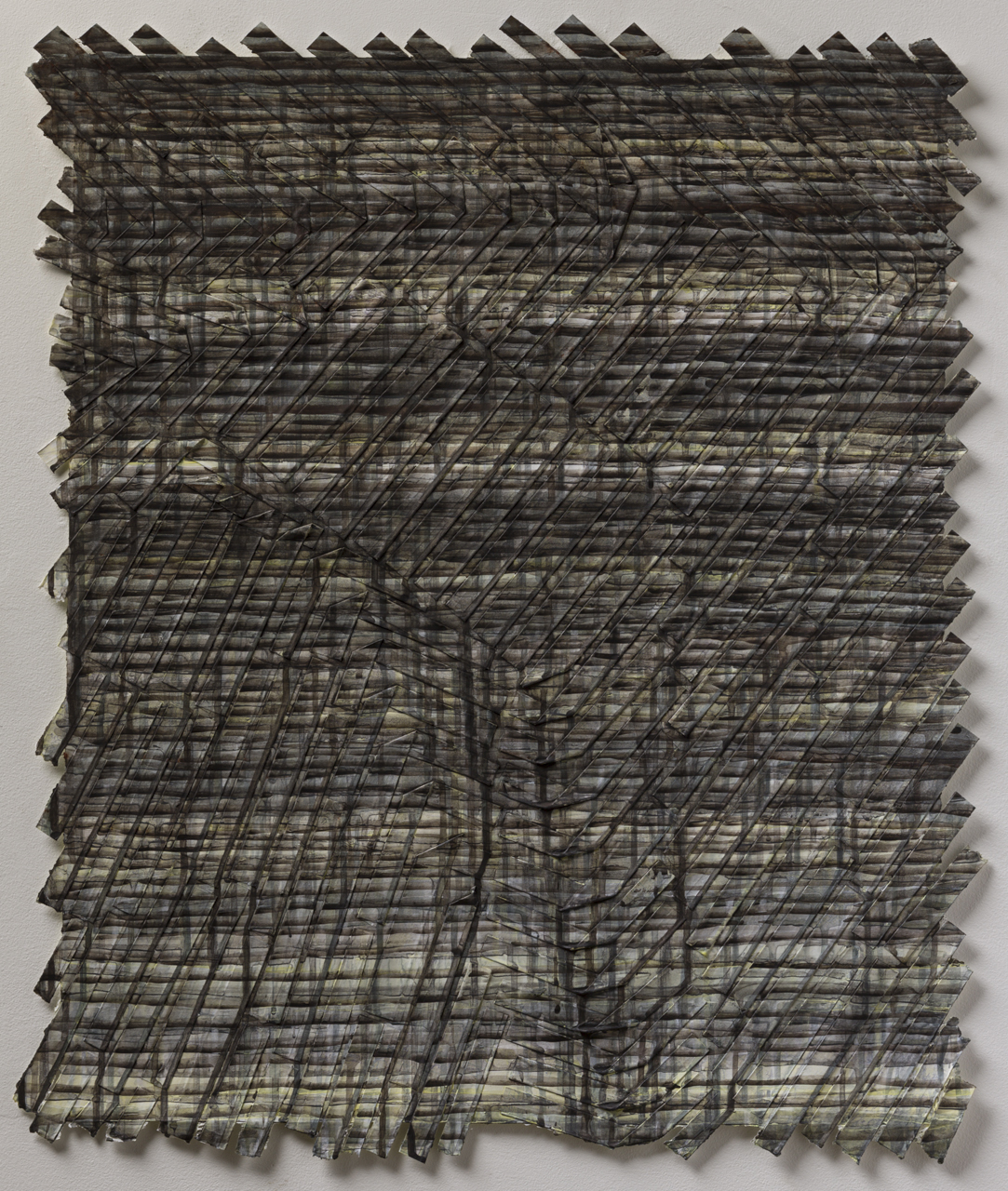

As I worked through ideas, thoughts, and desires toward this issue of Detroit Research, I began to orbit a number of questions: How might a choreographic sensibility and/or dancerly practice cohere in a way that is distinctively Detroit? And how can a choreographic lens offer an expanded sense of Detroit’s geography, as a socio-economic and historical terrain as well as a current or movement or mood inflecting discursive and aesthetic terrain? What would this look, sound, or feel like? Who can tell this story? The contributions to this issue of Detroit Research respond to these questions in diverse, urgent, and sometimes celebratory ways: artist/scholar and fourth generation Detroiter Maya Stovall’s choreo-ethnographic Liquor Store Theatre project; Danish [working in Sweden] choreographer, performer, and theorist Mårten Spångberg’s manifesto on art and culture within the machinery of capitalism; Hamilton Poe’s crowd-sourced photographic essay documenting the daily dances of a well known figure in Midtown Detroit’s swiftly gentrifying neighborhood; architect Allen Gillers’ mobile architectures that act as proposals for LGBTQ urban and affective commons; a score by improviser and choreographer Leyya Mona Tawil exploring experimental narrative in Arab American performance; Detroit born, Nigerian American performance artist Jaamil Olawale Kosoko’s poetic, performative texts and images excerpted from his recent performance piece “#negrophobia”; Theater and performance studies scholar Michelle Cowin-Mensah’s analysis of the performance of race and gender in Detroit’s notorious White Party; dancer and Detroit native Christopher Braz’s personal essay on voguing and belonging; and, lastly, a small collection of Ralph Lemon’s drawings that offer homage to Detroit’s music legacy.

In look and sound and feel, the work in this issue dances across disciplinary aisles—scholarly writing, drawings, photography, scores, reflections, poetry. Dance functions as both subject matter and methodological strategy, exemplary as an aesthetic point of entry into a range of intangibilities relating to place, identity, history, and art. One foot in front of the other, we enter the scene. We must, as Stovall stresses, have some skin in the game. Is dance so difficult to see? Perhaps dance helps make visible that which is very difficult to see. Sometimes we have to denaturalize the dance to see the dancer (or vice versa) shuffling his or her scene or, rather, opening up his or her scene through a shuffle, step, step, slide, pivot, twist, twirl. Dancing across aisles, outside of (disciplinary) houses and onto the street, can be risky. But it also reveals how movement is imbued with choreopolitical potential, dynamically placing us in the present and with one another.7The term “choreopolitical,” theorized by André Lepecki, articulates the impact of embodied, agential resistance to the current, often urban, … As we move with and against the city with courage, care, and criticality, let dance be our divining rod.

References