A Conversation with Carlos Diaz

Mary McNichols, Ph.D

All work and all photos by Carlos Diaz, courtesy of the artist.

While he initially considered a career in engineering, Carlos Diaz earned his BFA in photography from the Center for Creative Studies (CCS), now the College for Creative Studies, in 1980 and his MFA in photography from the University of Michigan in 1983. Diaz has been the recipient of many awards, including a 2010 Kresge Foundation Community Arts Grant. His work is installed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York as well as at the Detroit Institute of Arts among many other museums and galleries. It is currently represented by the David Klein Gallery in Birmingham and Detroit, Michigan.

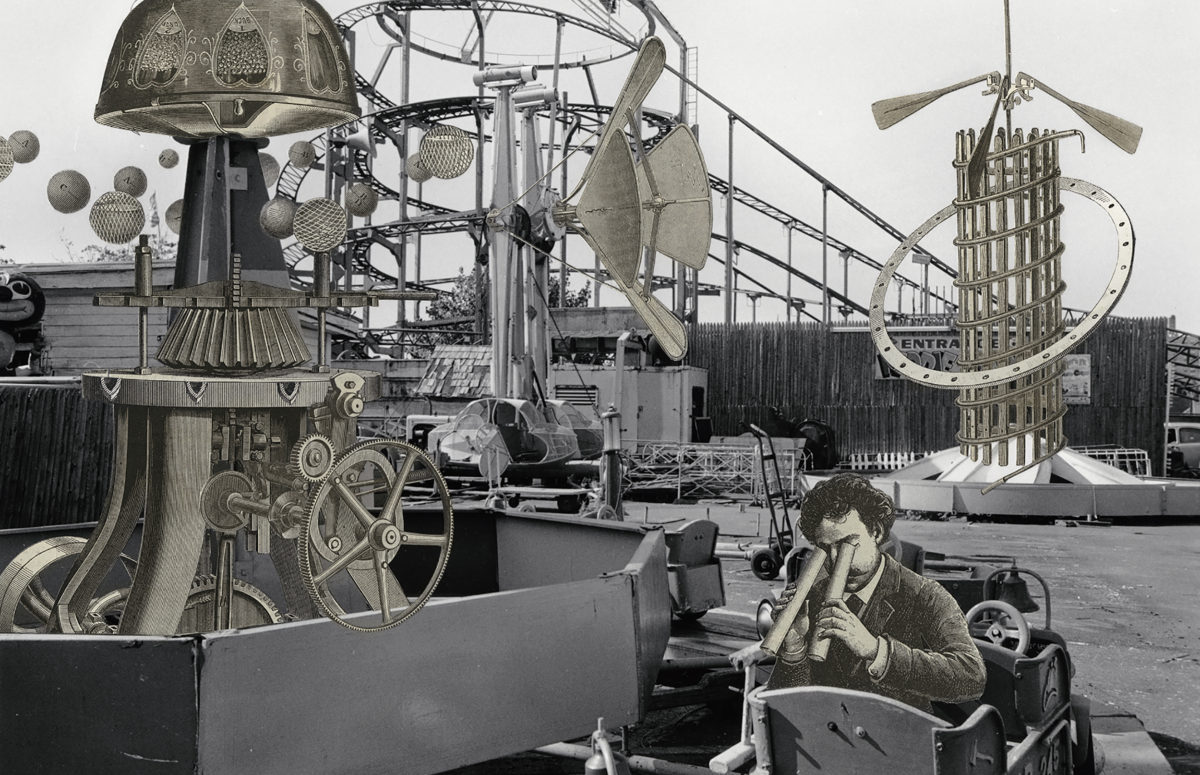

Invented Landscape, NYC 2005

Fun House RIde Attendant

Carnival Midway 20

Having been a member of the Department of Photography at the College for Creative Studies since 1984, Diaz also served as the Chair of that Department between 1994 to 2000. He is currently Professor of Photography at CCS. He has worked with Bill Rauhauser, both as his student and colleague during their respective times at CCS.

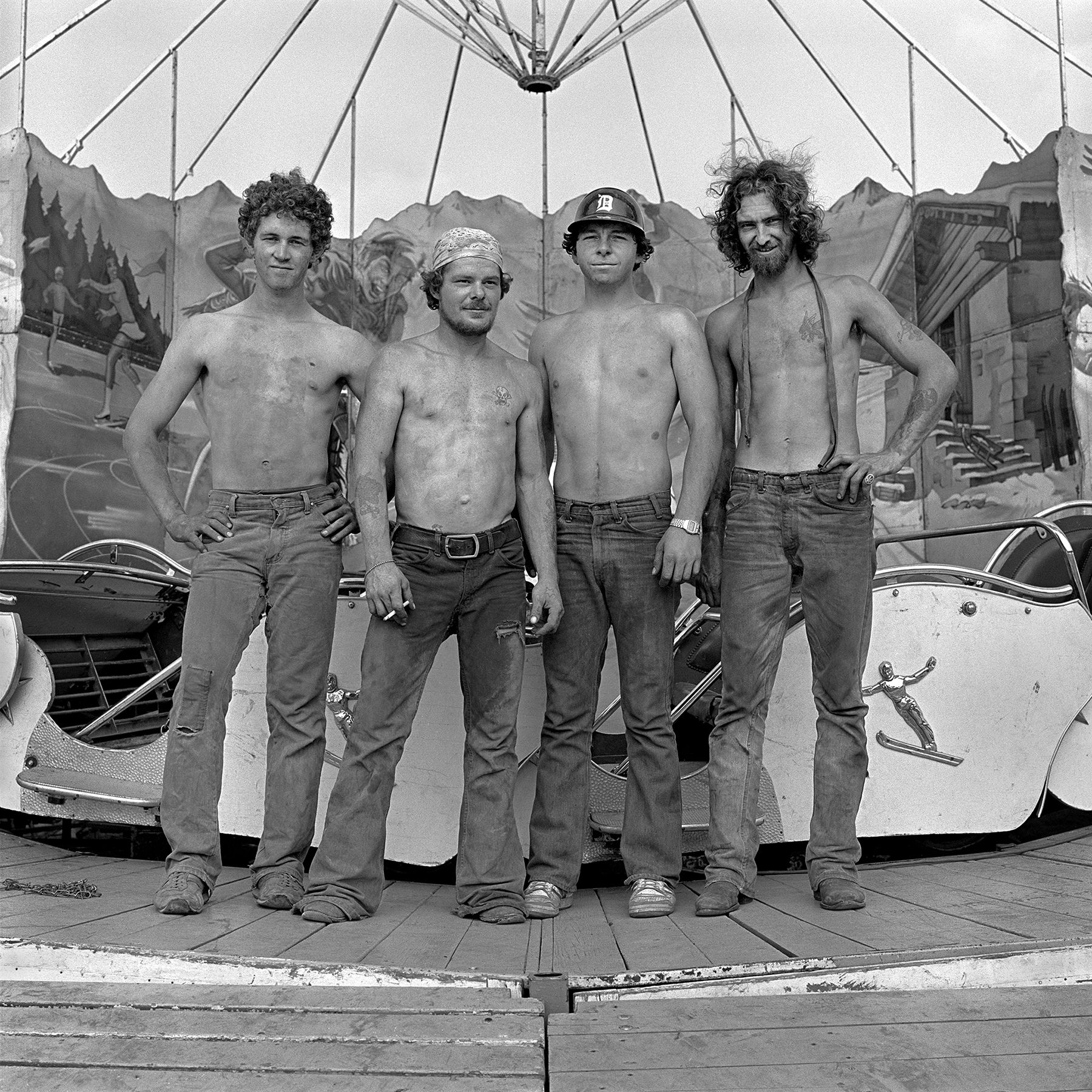

Carlos Diaz’s work in the carnival theme has evolved into three separate series: the carnival landscape; portraits of carnival ride attendants; and his Invented Landscape series, inspired by mechanical invention as well as his interest in the Coney Island Amusement Park. Diaz gravitates toward the paradoxical nature of the carnival offering, as it gives an opportunity for escapism while yet being, as the artist describes it, “a constructed artificial façade, a transient world made up of strange mechanical contraptions.” In photographs reminiscent of what Guy Debord characterized as a society of the spectacle, Diaz presents to the viewer – as actors on a stage – a poignant glimpse of the carnival attendants and the world that they inhabit.

Diaz’s most recent bodies of work are entitled Rouge: The Legacy of Detroit and the Autoworkers and Diorama: Destiny, Deceit, Displacement: The Native American and Manifest Destiny.

Mary McNichols: You grew up in Pontiac, Michigan, an industrial center, and worked in mechanical drawing and design for a number of years. What led you to leave your position as a mechanical draftsman and become a photographer?

Carlos Diaz: The short answer is that I had become bored and had lost the passion I once had for the profession. It began to feel like the same routine, day in and day out. The actual separation process probably began as a result of some of my early college class assignments which provided an opportunity for a much greater degree of exploration and creativity. After returning from the service around 1973, I was employed as a draftsman by General Motors at the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan. Word had gotten around that I had taken some photography/art classes at the local community college and was currently attending an evening photography class at the Center for Creative Studies (CCS), now the College for Creative Studies. After a couple of trial runs in the darkroom, the two company staff photographers soon asked if I would like to take charge of the darkroom facilities since they would both be away for several weeks shooting on location. I accepted the offer and, the minute I put out the sign, Do Not Enter – Processing Film, and turned on the darkroom lights, there was no turning back. That visceral connection to the darkroom and potential for magic that I felt then I continue to enjoy to this day.

About a year later in 1976, when General Motors’ contract with the government expired, my colleagues and I were temporarily laid off. This, of course, was the opportunity I had been waiting for, and I immediately enrolled as a full-time student at CCS. Subsequently, I was contacted for a number of job interviews, which I refused. As a result, I lost my unemployment benefits, but the G.I. Bill, scholarships and grants made up the difference, and the rest is history. It is a true testament to the connection between progress and taking chances, and I sometimes wonder how things would have been different had I not taken this leap of faith.

My experience and the three years that I attended CCS were transformative in so many ways. Soon after starting school, I took my first class with Bill Rauhauser; this was the beginning of a thirty-nine year relationship. The opportunity to work with Bill at this formative time in my career had a profound impact on the manner with which I would approach my work and my art. Through the years, Bill has been a mentor, friend, and source of inspiration to me, and when I began teaching at CCS 31-years ago, he was a guiding force and colleague. I feel extremely fortunate that our paths came together in such a meaningful way.

MM: How have those experiences – your life growing up in Pontiac and your experience as a mechanical draftsman – influenced your work in photography?

CD: Where and when I grew up has had everything to do with the work I produce and how I respond to the world around me through my work. My experiences growing up in the 1950s in a true working-class town and in a traditional Mexican-American community were formative. I like to describe my life experience at that time as the quintessential 1950s cliché. My parents did a very good job of sheltering my siblings and me from the realities of our family’s economic situation and from the world at large. I had few social experiences outside of my family circle and the Latino community. As a child, I remember my mother always having a camera around and often asking me to take pictures. As a result, those early years are well-documented and, in the future, the camera would become my access into other worlds!

After my father left the family farm in Saginaw about 1945, he moved to Pontiac to work in the Wilson Foundry. When he and his boss at the foundry did not see eye-to-eye, he quit that job and began schooling to become a barber. Although now officially retired, he continues – at age 91 – to cut hair to this day.

My father’s barbershop was about a mile and a half from our home and, somewhat reminiscent of an episode from the Father Knows Best or My Three Sons television series, my brother and I would take turns after school, walking along the railroad tracks from home to the shop to sweep the barbershop floor for a quarter. As a result of having seen, first hand, my father work at his practice through the years, my understanding and appreciation of the importance of passion and commitment to one’s profession was developed. Upon graduation, I knew that, as Pontiac was a quintessential working-class town whose epicenter was the auto industry, any healthy young man who was willing to work was guaranteed a job upon graduation from high school. But I wanted something more.

Various developments eventually led me to photography. During the sophomore year of high school, the school’s academic counselors met with each student and his or her parents to determine a career path. I had chosen the arts, but my parents insisted that I be placed in the “trade and industry” path which included mechanical drawing. Then, through the high school’s Co-Op program, I began to work at an engineering firm during my junior and senior years. After graduation, I worked full-time at an engineering firm from 1969 to 1971 while concurrently attending the local community college. When I was drafted in 1970, I applied for conscientious objector status, but ultimately entered the service in 1971. After an honorable discharge from the service in 1973, I was, ironically, employed by General Motors for the government’s Experimental Armor Tank Program. I left the drafting and design profession when I enrolled at the Center for Creative Studies as a full-time student. I had grown weary of the mechanical drawing profession and, although I had no intention of returning, during graduate school, I worked full-time for a year as a mechanical designer.

Given its intrinsic connection to the sciences and mechanics, photography became the nexus between my technical and analytical experiences and my developing interest in the arts. As a result of the many years of having practiced mechanical drawing, I had learned to see and to represent the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional plane. This is precisely what happens when a photographer looks through the camera’s viewfinder to ultimately conceive and construct a photograph. Whether consciously or unconsciously, both the inherently literal discipline of mechanical design and the expressive and interpretive nature of photography provide a place for my tendency and impulse toward formality.

For my carnival landscape project, The American Carnival Midway and, in fact, for the past 35-years, I have chosen to use an 8 x 10 view camera specifically because of the meditative, slow, and methodical manner in which one must work. The ground glass (viewfinder) on this camera measures 8 x 10 inches which provides the opportunity and space for careful and critical composing.

MM: Early on, you became interested in and researched the Industrial Revolution in this country and its relationship to the American amusement industry, specifically, carnivals, circuses, and amusement parks. You’ve observed that the advent of new machines and their efficiency changed American culture by affording the working class more leisure time. Please describe how this research has informed your work.

The Shaker Ride Attendant

Himalaya Ride Attendants

CD: Much of my work relates to my interest in the various forms of entertainment prevalent at the turn of the century and how these environments were in distinct contrast to the Victorian morals of the day. The Coney Island Amusement Park, the circus, circus sideshows, and the American carnival were manifestations of such places. Through collecting and reading books on this topic, particularly about Coney Island (made up of Steeplechase Park, Luna Park, and Dreamland), I began to see the intrinsic connection between the American Industrial Revolution, which gave birth to a new working class, and the resulting American amusement park industry.

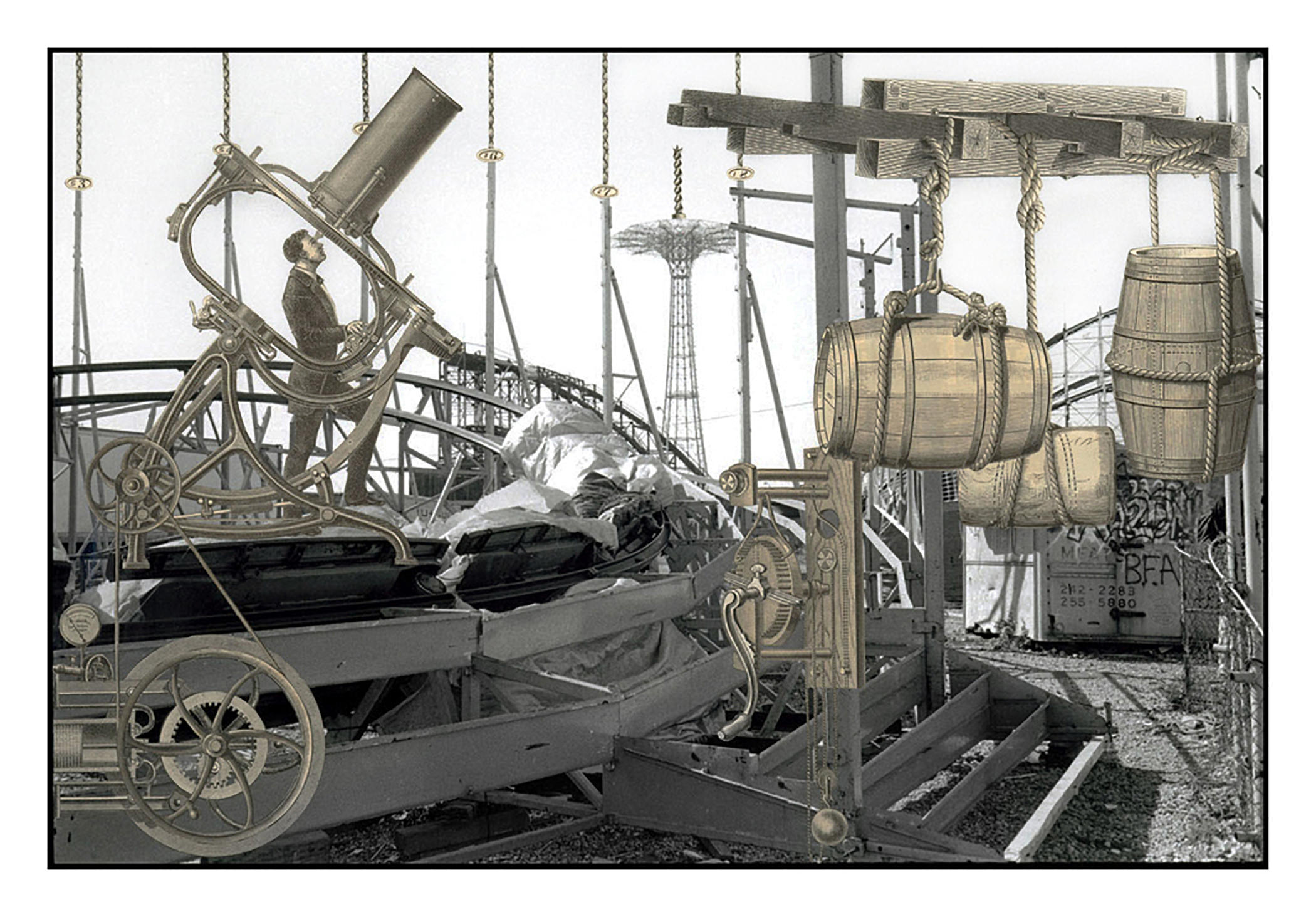

My series of hand-constructed collages, Invented Landscapes, on which I’ve worked from 1996 to the present, reflects these interests. In the Invented Landscapes, I combine vintage steel-plate engravings of mechanical inventions from the turn of the century (specifically from 1840-1890) with my photographs of Coney Island, made in 1994-1996. Each image is one-of-a-kind and hand-made. Using the illustrations of these newly-invented mechanical contraptions, I reconstruct – invent, if you will – fictional mechanical contraptions within the photographed amusement park environment. A primary intention in these images is to imply the paradoxical duality of the ethos of the period, as well as the contrast between freedom and restraint, pleasure and pain, the moral and the immoral. The Invented Landscapes are, simultaneously, whimsical and ominous and suggest, both literally and metaphorically, the functional forms of labor as well as the fun and fantasy of the carnival. Additionally, there are signs within narratives that refer to the relationship between humanity and technology. Here too, there exists a duality in that technology can be understood as both friend and foe.

Carnival Midway

Carnival Midway 2

MM: There is, of course, a tradition in American photography of the theme of side show performers. The perspective of these images ranges from that which would seem exploitive (nineteenth-century works such as Charles Eisenmann’s photographs in his book Monsters of the Golden Age; Max Rusid’s photographs in his publication Photo Album of Human Oddities; as well as those of Frank Wendt, himself a student of Eisenmann) to those of Diane Arbus which seem to go beyond purely objective images to delve into the poignancy of the lives of her subjects. Please describe the perspective of your portraits of carnival people.

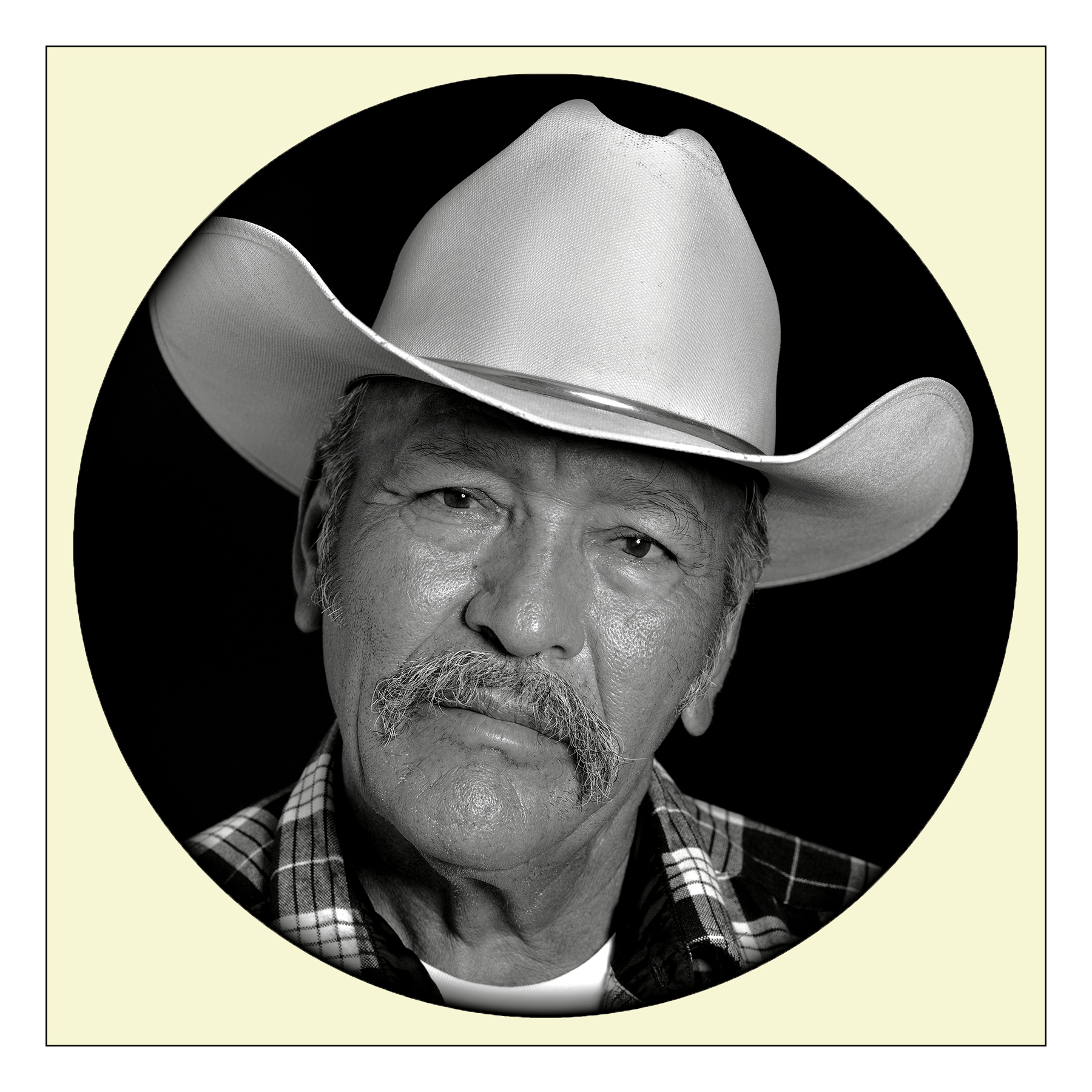

CD: There certainly were instances of exploitation, but the photographic portraits that Wendt and Eisenmann in particular made were instrumental in establishing the popularity and, consequently, the demand for the best-known “freaks” of the period. For these physically-impaired “human oddities,” the circus sideshow was their only means of income, and most understood the importance of being photographed. My carnival portraits, as well as the black motorcycle rider portraits, were done out of a sense of wonder and curiosity. I wanted to know and to better understand these groups of individuals who are seen as outside the mainstream of society. They are groups on the fringe, on the edge. In the case of the Latino immigrant portraits, my intent was slightly different. In this case, I wanted to express what I already knew and the stories I’d been told about these individuals. The act of photographing them implied a degree of greater importance. On another level, to better understand “the other” is to better understand “the self.” For me, the camera has provided a means to access, as well as to gain permission to enter into, subcultures usually denied. By photographing these individuals, ultimately, I am paying homage to them. When you isolate individuals through the camera lens, you confer upon them a higher degree of humanity.

MM: You stated during your lecture of October 1, 2009 at the Focus on Faculty exhibition at Center Galleries at the College for Creative Studies that “The classic struggle between good and evil, the sacred and profane, is at the center of my work.” Please elaborate on how this overarching theme is reflected in your various series.

CD: In essence, I see the carnival, the circus, and Coney Island in particular as a metaphor for life. These places represent the dichotomy inherent within life itself: on one hand beautiful and utopian; on the other, ugly and evil. On a broader level, I have described these artificial landscapes as a Surrealist dream or nightmare where the unconscious and the irrational are manifest. As a culture, we thrive in a world of escapism, and the photograph and photographically-reproduced image has transformed us into “members of an image-sodden species.”1A. D. Coleman, Depth of Field (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), 64. Guy Debord, the French Marxist theorist, writer, filmmaker, member of the Leftist International, and founding member of the Situationist International, coined the phrase society of the spectacle. He believed that capitalism was transforming culture into a façade of spectacle, into a world of artificiality.2Cf. Steven Best and Douglas Kellner, The Postmodern Turn (New York: Guilford Press, 1997), 94. The carnival and Las Vegas are classic examples of such places. Here, we are transported to exotic and unworldly places where we embrace that which we know is not real and look beyond the façade. Here we are transformed and swept away into a world of decadence. At the turn of the century, the amusement parks were in stark contrast to the Victorian “code of conduct” of the period and served as places for fun, fantasy and escape.

MM: Please describe your approach to your subjects.

CD: My portraits are an attempt to present some truth about the subject before the camera, and are not staged. I will almost always photograph my subjects as I find them and only ask that they look into the camera. It was when I first saw the work of Diane Arbus that I began to understand the emotional and visceral power of the photograph when you looked at the subject and the subject looked back at you. The way subjects naturally present themselves to the camera is revealing in and of itself. This lack of intervention provides an opportunity for improvisation and chance. My process is to first engage the subjects in conversation to know them better and, secondly, to allow them to become more comfortable in front of the camera and to present something of what lies beneath the skin. My subjects recognize and accept that they are being photographed. They have a choice to be photographed or not and, when they choose to be photographed, they enter into a collaborative agreement with me.

MM: Much of your work is concerned with social issues – with, as you have described it, “issues that lie below the surface.” Your portraits of carnival people are, of course, an example of this interest. Please describe your installation piece The Unemployed Auto Worker exhibited at Pontiac’s Creative Art Center in 1991, within these terms.

Installation, The Unemployed Auto Worker, Pontiac Creative Art Center, 1991

CD: The Unemployed Auto Worker installation was my first and last installation to date, although, I am considering an interactive installation of my Latino Immigrant series. The Unemployed Auto Worker installation resulted from a conversation with my older brother, just recently laid-off from his job of twenty-five years with General Motors. When we spoke, for the first time ever, I heard a sense of uncertainty in his voice. At the time, the media never provided the names and stories of those who had lost their jobs, but rather, individuals became mere statistics in its coverage. I wanted to give a face to the faceless.

First, and in an act of protest, I wall-papered the gallery walls with local newspapers, symbolically emphasizing that the media was thoroughly covering the event. Second, I built a frame structure to simulate a typical working-class living room, enclosed it in see-through plastic, and floated the structure from the ceiling. Typical living room furniture was placed in the room, including a television. Third, I included videotaped interviews of ten unemployed auto workers and a VHS player. In the gallery, I installed photographic studio portraits that I had made on-site of the same ten unemployed autoworkers. The photographs, which I had printed larger than life, were hung with fish string several inches away from the walls to deny their presence as works of art. Finally and most importantly, during the duration of the exhibition and to express the importance of the individual worker, I “hired” and paid various unemployed auto workers to be present in the living room to talk with and to answer questions from visitors to the exhibition.

An exhibition of historic automobile manufacturing photographs from the Ford Historical Archives which I had curated, and which included Charles Sheeler’s iconic 1927 work Criss-Crossed Conveyers from the Ford Rouge Complex, was installed in the upper gallery. Additionally, local union chapters were invited. They displayed historical union documents and paraphernalia.

MM: Photographs from your most recent series, Beyond Borders: Latino Immigrants and Southwest Detroit, some of which were installed in the 2011 Detroit Institute of Arts exhibition Detroit Revealed: Photographs 2000-2010, include both portraits of the Latino immigrants who live in that neighborhood as well as photographs of their homes. Please describe the perspective of this series.

Latina Immigrant, Haylie Eduia

Latino Immigrant, Gabriel Arteaga

Latino Immigrant, Juan F. Almanza

CD: Part 1 of this portfolio, Beyond Borders; Latino Immigrants and Southwest Detroit, is a series of portraits intended to celebrate and pay personal homage to the Latino immigrant. My father was a migrant worker, farmer, and foundry worker before becoming a barber. From an early age, he would tell stories about his father’s journey north to America and the struggle to survive the odds he had encountered in pursuit of his dreams.

On the title page of the portfolio, the following is included:

Tonight we shall eat the

assumptions of ourselves

of our house and where

we are going

Tonight we shall embark on

the Floating Borderlands

toward our liberation.

– Juan Felipe Herrera3Juan Felipe Herrera, quoted in The Floating Borderlands: Twenty- Five Years of U.S. Hispanic Literature, ed. Lauro Flores (Seattle: University of …

Although my father’s story is not necessarily unique, as there were many who were willing to leave their home country for what they perceived to be a better and more prosperous life, his experience as that of all the others is unique! Today Latino immigrants are blamed for a host of social ills and, as “non-citizens,” they make easy targets and convenient scapegoats. Since immigrants are legally deprived of many of the rights that U.S. citizens enjoy, including the right to vote, elected officials and the general public can overtly blame, marginalize, and discriminate against them with little repercussion. Today, as in the past, Latino immigrants form the latest iteration of cheap labor, having no contract, no representation, and few rights. Our agricultural economy is, in fact, dependent upon just such a population.

The Beyond Borders project began several years ago because of my outrage at the perpetually deplorable manner in which Latino immigrants were being portrayed en masse, both publicly and politically, as illegal, undocumented, and alien. During state and national elections, and for the perceived benefit of the politicians, the “immigrant problem” is used to inflame, and in a manner that is intended to systematically deny the individual immigrant’s identity. This is a simple but effective strategy because when we begin to identify with the individual, we begin to recognize the inhumanity imposed upon these people! Throughout America’s history, when economically advantageous, we have welcomed and, indeed, recruited the immigrant to this country to work in the fields and factories and in our homes and hotels. Then, when the political climate changes and immigrants are no longer needed, with political red, white, and blue spectacle, we deny that welcome through harassment, deportation, and by building walls. I would agree that this constitutes a policy of what might be described as in the back door and out the front.

I see the Mexican/American border, the wall, the river and the desert, as symbols of the classic demarcation between desperation and hope. My intent is for the faces in these portraits to be read as a road map of the immigrants’ experiences – their unique set of circumstances and the story of their journey from the border north. The circular motif framing the subject is reminiscent of seventeenth-century Flemish painting and is intended to represent the immigrants as nobility and aristocracy. These portraits are, then, my attempt to personify the people of this community by removing the mask that these individuals have been forced to wear.

Part 2 of the portfolio, Beyond Borders; Latino Immigrants and Southwest Detroit, is a series of the homes of Southwest Detroit.

During the summer of 2010 while making the immigrant portraits that form the first part of this portfolio, I began taking walks through the neighborhoods of Southwest Detroit. During the process of making the immigrant portraits, I simultaneously audio-taped conversations with the subjects. As a result, each individual’s set of circumstances detailing his/her trip north beyond the border came to light, and the explicit details revealed by each immigrant’s story were beyond my imagination. These walks through the neighborhood began partially as a result of my not being from the Southwest Detroit community; however, in the end, my experience became both a tangible and transcendent way to identify with the people in the portraits.

The beautiful and warm seasonal light, the cool breezes and especially the newly-formed foliage and blossoms were all evidence that late spring and early summer had arrived in Southwest Detroit. In many ways, what I saw during my walks in the neighborhoods was in direct contrast to the ill-informed image I had been given about this place. Ultimately, both the well-defined spaces and the homes attracted me. The homes were what you would expect from anyone, anywhere who cared and tended to his or her personal domain. These were beautiful spaces and, for Latino immigrants and others, they reflected both the new world of which they were now a part, as well as the one that they had left behind. Southwest Detroit is approximately 50% Latino and, although I did not know for certain whether the homes in my photographs belonged to Latino immigrants, there were clues: religious and ethnic iconography and statuary as well as Mexican flags were commonly displayed. Southwest Detroit is a vibrant oasis teeming with life and this was simply a beautiful time to explore these neighborhoods.

I refer to these photographic images as “pedestrian views” because they are literally points of view that anyone would see with feet on the ground and eyes wide-open. I met and talked with many people along the way, and they were friendly and gracious. I soon began to feel as if I were at home.

MM: You’ve stated that you have done no “long-term, serious work” in color. Please explain your choice of black and white photography – aesthetic or thematic.

The Rouge, Steel Worker No.7

CD: When this statement was made, it was true. During my undergraduate years, much of the work that moved me – that I connected with and that initially triggered a serious interest in photography – was black and white. Although this began to change in the 1970s, color photography had not been the choice of serious art photographers. Beyond that, when the subject and intent are compatible, I have worked in and continue to work in black and white. When you strip away the color layer from the subject and record it in shades of gray, you are further interpreting, transforming, and translating the subject. Now, because of the popularity of digital cameras and the proliferation of photographic images in our culture, black and white images are seen as exotic, historic, and antique. When I now use black and white, I do so because of its inherent separation from reality and from the present. There is an immediacy with color; color is the here and now.

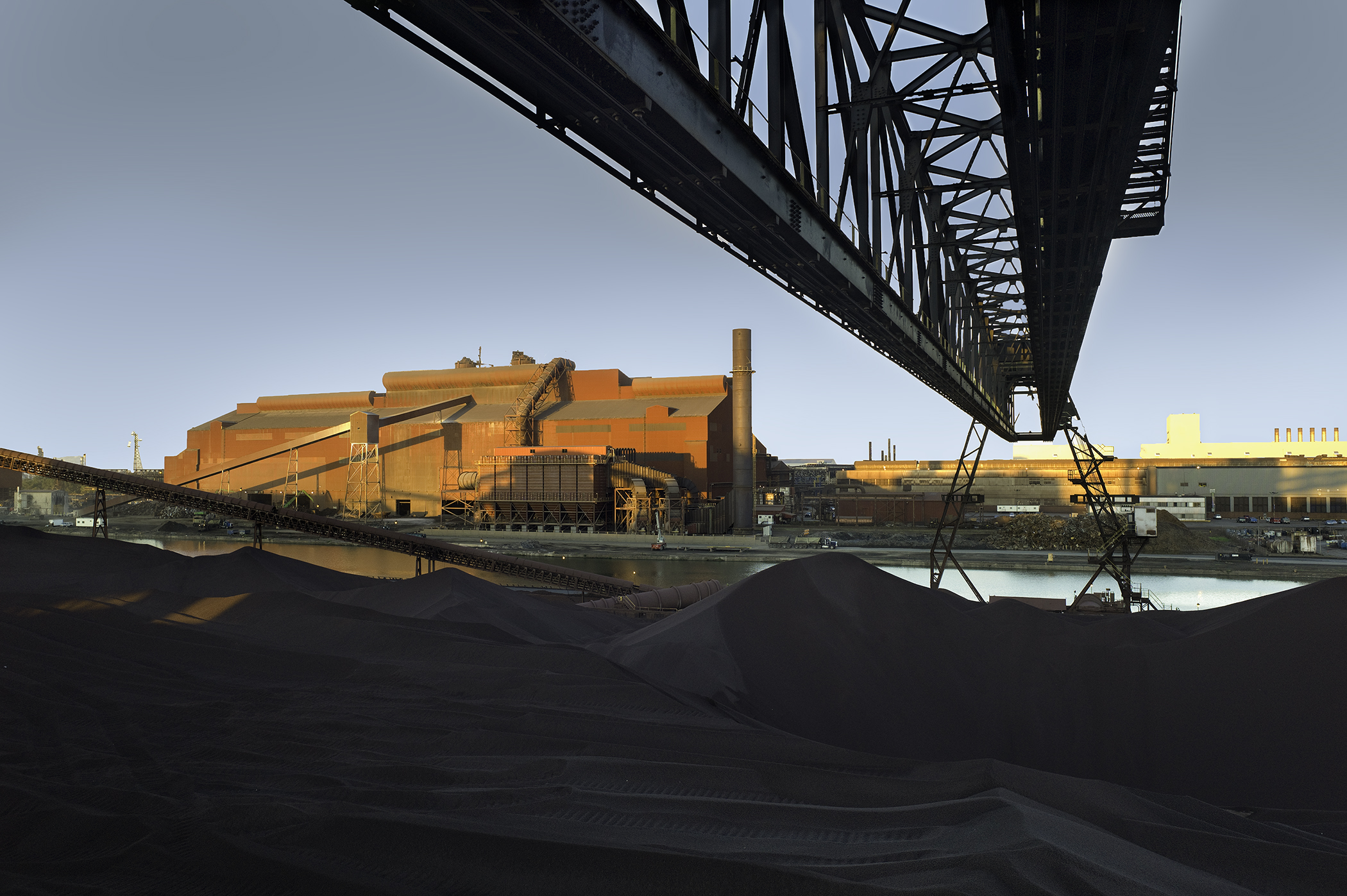

The Rouge, Looking South Along the Highline, No.1.

The Rouge, Above Storage Bins, From Transfer Crane, No.9

The Rouge, From the Transfer Crane, Looking West Over Boat Slip, No.8

The Rouge, Looking Southeast to Blast Furnances A and B, No.5

Aside from the color assignment work that I did as a student, I began to use color for the first time in 2010 when I began the Beyond Borders: Latino Immigrants and the Homes of Southwest Detroit project. As I recounted earlier, during the summers I began taking walks through the neighborhoods of southwest Detroit. Initially, I was attracted to the lush late spring foliage and the rich colors. I responded not to a feeling of history or nostalgia, but to the immediacy of where I was and what I saw. I became absorbed by my surroundings at that moment.

In 2012, I began making photographs for a new body of work, Rouge: The Legacy of Detroit and the Autoworkers. Through a friend, I met an individual who was able to secure complete and total access to the old Ford Rouge Complex, now owned by Severstal. This was an exceptionally rare opportunity. In the past, I, as well as many others, had tried for years to gain access with no success. I began printing these images in black and white and, when I showed them to friends and colleagues for feedback, I received very favorable comments. In time, as I continued to look at and think about the images and, after reading about and spending more time with Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals, I realized that the images in black and white seemed to be anchored in the past, and were not compatible with my interest in and intent for my subject. I also worried that they would only be seen as “historic documents.” These new images of the Rouge were not made in an attempt to look backward, but instead, to represent this post-industrial cathedral in the present as well as to recognize the importance of the laborer in the automobile manufacturing industry.

The second part of this Rouge series will consist of environmental portraits of retired Rouge workers in their homes. Before I photograph, I’ll audiotape interviews with the workers about their past experiences working at the Rouge. In this instance, I have chosen to make traditional documentary portraits in black and white.

So, to address your question, the choice between black and white or color is not conditioned by “aesthetics” but rather by subject matter, concept, and intent. In the end, I must determine which of the two is more compatible.

The Rouge, Steel Workers Glove

The following bibliography, by no means exhaustive, consists of works important to Carlos Diaz.

Best, Steven, and Douglas Kellner. The Postmodern Turn. New York: The Guilford Press, 1997.

Jean, Marcel, ed. The Autobiography of Surrealism. New York: Marlowe & Company, 1952.

Cabadas, Joseph P. River Rouge: Ford’s Industrial Colossus. St. Paul: Motor Books, 2004.

Chomsky, Aviva. “They Take Our Jobs” and Twenty Other Myths about Immigration. Boston: Beacon Press, 2007.

Coleman, A.D. Depth of Field. Alburqueque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

Cummings, Frederick J. The Rouge: The Image of Industry in the Art of Charles Sheeler and Diego Rivera. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1978.

Durozoi, Gérard. History of the Surrealist Movement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Ezrahi, Yaron, Everett Mendelsohn, and Howard P. Segal, ed. Technology, Pessimism, and Postmodernism. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994.

Fiedler, Jeannine. Photography at the Bauhaus. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990.

Flores, Lauro, ed. The Floating Borderlands: Twenty-Five Years of U.S. Hispanic Literature. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998.

Jay, Ricky. Jay’s Journal of Anomalies. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2001.

Miller, Dennis. Photography’s Multiple Roles: Art, Document,

Market, Science. Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, 1998.

Postman, Neil. Technology: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Stebbins, Jr., Theodore E. and Norman Keyes, Jr. Charles Sheeler: The Photographs. New York: Little, Brown and Co., 1987.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions and Practices. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis, 2003.

Urrea, Louis A. The Devil’s Highway. New York: Little, Brown & Company, 2004.

Valdes, Dennis N. El Pueblo Mexicano en Detroit y Michigan: A Social History. Self-published, 1982.

Wells, Liz. Photography: A Critical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Wells, Liz. The Photography Reader. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Zolberg, Aristide R. A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

References